Two-Part Names & Other Joys: An Interview with Faith Zamblé

The Civilians' Resident Dramaturg Phoebe Corde sits down (virtually) with Extended Play editor Faith Zamblé to talk dramaturgy, research, and more.

Sign up to get spam-free email updates to ensure you never miss an article and to receive exclusive details about performances and events from The Civilians.

Ilana Becker: Can you tell us a little bit about your work focus before you began writing plays?

Darrel Alejandro Holnes: Before I began writing plays I was really involved with ethnographic research that was happening out of the University of Houston in partnership with the Library of Congress. We collected interviews with survivors and evacuees of Hurricane Katrina who mostly fled New Orleans–or surrounding areas in Louisiana and the Gulf Coast–to Houston. And then when Hurricane Rita hit, we started to also collect stories from survivors and evacuees of Hurricane Rita. Those stories are stored in the American Folklife Center’s archives at the Library of Congress. The project was led by Dr. Carl Lindahl and Pat Jasper, who is a public folklorist. It was a really great experience that taught me the value of narrative and the value of an everyday story. Because an everyday story is an extraordinary story.

Ilana: How did you connect with the people you interviewed?

Darrel: All of our interview partners were volunteers. From what I recall, a lot of how I came across folks to interview was through faith communities. And because a lot of folks, when they evacuated, were trying to re-establish themselves in a new city, one of the first things that they would do — especially if you are living within the Bible Belt — is go to a local church, go to a local temple, go to a local place of worship and establish community. These were also places of charity and a lot of the folks that we were interviewing were in need. And so they were one of the many common spaces where we were able to meet folks who were interested in sharing their stories whose voices weren’t being heard. At the time, there was so much negative press about Hurricane Katrina survivors from New Orleans in Houston, that many folks, especially from within the Gulf Coast community affected by the hurricanes, were really interested in setting the record straight and providing their own stories to rectify the misinformation that was being reported in the press about them.

“I also love those interviews where I walk away, myself, transformed. When we’re receptive to it, we become each others’ teachers when we least expect.”

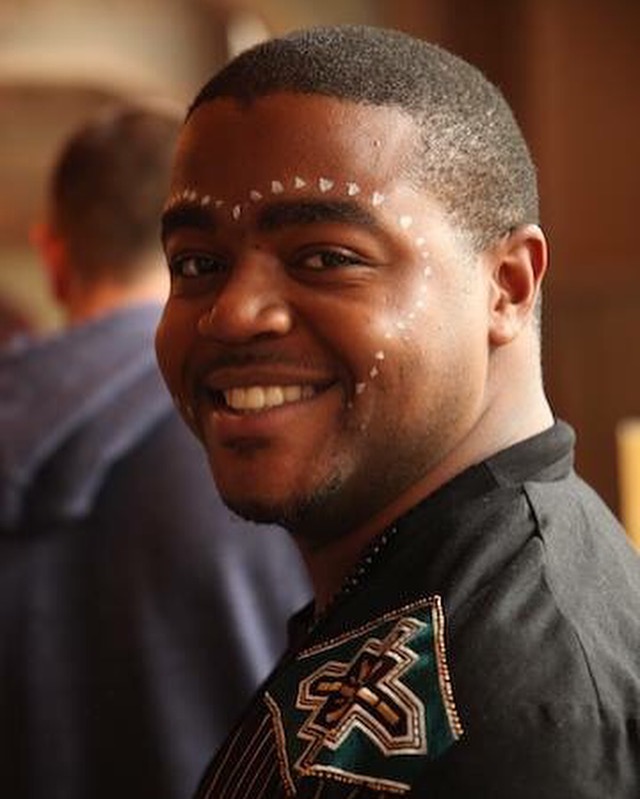

Darrel Alejandro Holnes

Ilana: How has that need to set the record straight about folks’ stories straight shaped the work you do as a playwright?

Darrel: I think it’s influenced me greatly because I see it as a kind of activism. It’s important for me to tell stories about people who have been ignored or forgotten. If they’ve been left out of the American history books, I’m hoping to write them into the history of the American stage. It’s why I do what I do – write research-based plays. So many of the stories overlooked by the media, left out of the history books, are the stories that need to be told today. Their stories needed to be heard.

Ilana: What led you to develop your current research and interview process?

Darrel: When I was in graduate school I took a course with Dr. Ruth Behar. She is this incredible, incredible researcher who developed what some scholars have called “the anthropology of the heart”. It’s a way of connecting with the interview subject, or I like to say “interview partner” — it’s a way of connecting with them on a level that is personal and narrative-based, and it also allows them to guide you towards what they think is important about their story to tell.

That’s different from a more patriarchal method of research that was grounded in white supremacy, where you’d find these typically white male anthropologists from Western Europe or the United States, who would go into a community and tell that community what was important to the academie, ask the people whose customs they were studying their research questions, and tell them who they wanted to talk to instead of asking the community to choose its own representatives. It’s not really fair.

Ruth Behar was one of the anthropologists of a new school that were trying to turn the tides. This appeals to me greatly as a creative writer because my goal is to tell a story that matters to the heart. So when my interview partner is speaking from the heart it allows me to find the elements of the story that are poignant and moving and transformative for the audience because these are the parts that are typically also transformative moving and poignant for the person who’s experienced these stories.

I found it to be really helpful to have taken her class, and it was also very much in line with the survivor-led project that I did as an undergrad with the University of Houston and Library of Congress. We had survivors interview survivors, evacuees interview evacuees. I evacuated from New Orleans because of Hurricane Katrina, and then I evacuated from Houston because of Hurricane Rita. So these were members of my community even if I wasn’t properly from New Orleans and I even though I didn’t really grow up on the Gulf Coast. Survivors and evacuees were still part of my community through our experience with these hurricanes. And those community members were the ones that were determining the focuses of the project. I like my work to follow the same or a similar model.

When I interview folks, I always try to build open-ended questions that allow them to walk me down the road that they find to be most important, and to take me past destinations that they want to see, that they want to be reminded about, that they want to share. That’s really the story of my research and how I developed my interview methods.

Ilana: Can you share with us your impetus for writing this play?

Darrel: The play that I’m developing for the Civilians’ R&D Group is a play inspired by one of the stories that I collected when I was in Berlin — from the black community in Berlin. And it’s the story of an Afro-German who is neurodiverse, who is on the spectrum, and is negotiating his challenges with his autism and connecting with the larger German Society at the same time that he’s navigating his identity as a black male within a predominantly white landscape.

And so it is a story that sits at the intersection of neurodiversity and race. And it’s something that really moved me when I heard the story because it’s one that I had never really heard before. I knew it was a story that needed to be told; I knew that it was a story that needed to be heard. I collected many other stories during my time there doing research within the community, but this one always stuck with me.

Ilana: How did you find your research methods taking shape as you got to know the interview partner who brought the story in your play to life?

Darrel: That interview partner was a point of access to other folks. At first he was very busy; he could sort of like meet me late at night for a drink or something and he introduced me to some people, but he really wasn’t available to sit down for an interview in a formal setting. I think he just wanted to see how it went before he allowed me to interview him. After gaining his trust and spending more time with the community, I finally had a chance to sit down with him. By that point we had had a lot of different conversations and he had taught me a lot about neurodiversity already. I think he — I might have heard the term before, but I never even really talked about that term with someone until I had a series of great conversations with him about the challenges that he dealt with. I think he felt like he found a sympathetic ear, because then afterwards he agreed to actually be recorded. We had our interview and I just learned so much from him! I love those interviews where I also walk away, myself, transformed. You know? It feels like it makes the work all worth it. When we’re receptive to it, we become each other’s teachers when we least expect.

The conceit of my play, or the form of it, is in the form of the video game. And that is inspired by details from the interview. If there is anything the current political landscape in the United States has revealed, it’s that the realities that people in one part of the country live in, are not the realities that people in another part of the country are living in. There’s more than even just those two realities — there are multiple realities along the lines of region, race, religion, class, etc.

And then there’s also this other space of news media and of social media, where everyone can escape and dive into another reality that’s not their own. Or dive further and further into what they think reality should be, right?

And so I think that as a society today, we are facing a lot of questions like, “Is the virtual space more important than the lived space?” “In what ways is the lived space a virtual space?” “Is it in that it’s a product of our own impressions and our own perspective?” And is there something disorienting, is there something challenging, is there something about that that starts to make that reality less real the further down the rabbit hole we fall? Those are also questions that have found themselves into this play, as well.

Black Feminist Video Game, the first play in the AFRIKAN•ISCH cycle, will have a work-in-progress showing on June 24th at 7:00pm. RSVP here.

This interview was conducted on April 10, 2020. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.