Two-Part Names & Other Joys: An Interview with Faith Zamblé

The Civilians' Resident Dramaturg Phoebe Corde sits down (virtually) with Extended Play editor Faith Zamblé to talk dramaturgy, research, and more.

Sign up to get spam-free email updates to ensure you never miss an article and to receive exclusive details about performances and events from The Civilians.

April Matthis in rehearsal for "The Way They Live," the final production of the Civilians' residency at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo Credit: Micharne Cloughley.

April Matthis in rehearsal for "The Way They Live," the final production of the Civilians' residency at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo Credit: Micharne Cloughley.In visual art, the label “negative space” refers to the empty space around a subject. It is possible for a subject to seem accurately portrayed, but the space around the subject may not ring true.

I was reminded of the term while working on a new play at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The play — the final work of the Civilians’ yearlong artist residency in the museum —represented an investigation of the American Wing and borrowed its title, “The Way They Live,” from the Thomas Anschutz painting in the collection. To create the script, I interviewed the American Wing curators and staff and led a team of 12 field researchers in interviewing visitors and contemporary artists in the Wing. At the heart of our investigation was the question, “What does it mean to be American?”

With 90 minutes of stage time to explore this ambitious question, I was acutely aware of the limited amount of history and perspectives on American identity that we could cover. The negative space of the play — all that surrounded the subject but was not included — was equally important territory as the featured narrative.

Any writing process has a negative space, which will always be huge and may feel indefinite, even if you’re not writing a play about what it means to be American. In written work, the negative space is not so easily identified; there are no obvious lines as in the visual arts. But thinking of what we don’t include in a work as a defined space may assist in increasing diversity in writing across media. Diversity can begin with the writer, who makes specific choices about what is being left out.

In applying the term to the American Wing, the volume of negative space is clear in the common first impression: “Why doesn’t this wing look more like the America I know?” Curated histories have always excluded groups of people, based on the identity of the curator. Upper class white men historically curated the American Wing collection, and so it follows that the collection largely contains artwork made by and featuring upper class white men. The collection is mainly limited to the period pre-1930, a time when vast, explicit inequalities based on race, gender and class impacted one’s ability to become an artist and be collected.

This visible negative space in the collection reflects the current lack of diversity endemic to art forms throughout popular culture. However, diverse stories do exist within the collection, and exciting new acquisitions are working to tell a richer story. The curators I interviewed spoke passionately about including diverse voices in the wing, guiding me to works that tell stories beyond the white-male narrative.

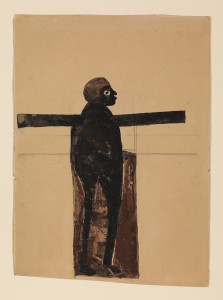

“Black Jesus” by Bill Traylor. Photo Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Many of these works were featured in the final production. For example, “Black Jesus” is a work by Bill Traylor, an African American self-taught artist, who began creating work in his 80s. His artwork inspired a wide range of responses, especially when the interviewee was told that a collector — and not Traylor himself — might have named the work “Black Jesus.” Some people identified religious themes in the work, another saw imagery of the Native American Yup’ik people in the portrayal of the figure’s eye in the painting, and several people celebrated the fact that Traylor shared gallery space with Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent.

In focusing in on such works in the script, I needed to build a new negative space in the American Wing through our interpretation of its contents and their meaning. First and foremost, I wanted to put my own bias into this negative space. I am a 30 year-old Australian female. Also my sister is a conservator, which has greatly influenced the way I approach art. Being aware of my identity and its influence over the investigation, I would work to eliminate my personal voice from the play, which included both my actual words and preferences in terms of art and history. However, even this choice has a bias, in that female artists often shy away from representing traditionally feminine qualities in their work or process. I was assisted in ensuring that such qualities would not be ignored, as the entire curatorial staff of the wing is now women. Feminine perspectives were going to be very present without my own words being used.

The interview that initially raised the term negative space was on the lone work in the play (and one of a small percentage in the Wing) by a woman artist: “Portrait of the Artist” by Mary Cassatt. The interviewee, a college-aged female art student, tried to identify “what was wrong” with the work and questioned its various technical aspects, including the negative space. Other interviewees, both male and female, stumbled around why they didn’t like this painting. For example, one educator mentioned that, at the beginning of her career, she included Cassatt in her teaching, until a student directly told her that she wasn’t as passionate about Cassatt’s work as that of other artists.

“Portrait of the Artist” by Mary Cassatt. Photo Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I finally included interviews on Cassatt’s work from two members of the staff of the Wing. They presented a rare highly celebratory perspective and one of many highly critical opinions. The critical response compared Cassatt’s work with male self-portraits, which “own” the act of making their art. Cassatt however was “leaning out” in her weak portrait of herself, she needed to “like, lean in!” This reference of the staff member to Sheryl Sandberg’s polarizing book summed up the other interviewee’s dislike, that included that the proportions of her body were distorted, the coloring was “weird” and she didn’t portray herself actually creating art. Through the use of the expression “lean in,” the work resonated with a contemporary audience, reflecting on feminism both at the time the work was created and today.

Ultimately the negative space of the play became a reflection of the material in the work itself. The negative space was simply less articulate, repeated material. The sample that was included in the play was an accurate portrayal of the spectrum of interviewees’ thoughts and feelings about representations of colonization, immigration, race, gender and wars. Such a sample is of course limited in 90 minutes, but we found that people hold contradictory points of view within their opinions, and so we sometimes were able to address multiple perspectives in one actual voice.

It is not always possible to so clinically define an artwork’s negative space, nor is it always possible to so cleanly be able to include a wide cross section of material. Within one play, we devoted attention to a large number of issues at the forefront of America today. Perhaps the most important negative space for any work — visual, theatrical or otherwise — is that which we feel. Sometimes, as an audience member, you are conscious of specific information the artist hasn’t included, and it makes you feel uneasy. As in seeing a visual artwork, the source of this unease may not be immediately obvious. But once you analyze the work technically, you realize the negative space is distorted. The line between right and wrong is often subjective in art. But the line between positive and negative space, if one is striving for a technically accurate representation, is much more objective. After all, there is a definite line. A line you can get wrong and is not so easy to fix, as it affects the perspective of the rest of the work. We can learn a lot in the theater by considering the deliberate negative space of a work, both as artists and audience members. A beautiful negative space is integral for a beautiful artwork.

“The Way They Lived” was performed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on May 16 and 16, 2015. Micharne Cloughley wrote the script, based on interviews performed in the Met’s American Wing between 2014 and 2015. Mia Rovegno directed a cast that included Damian Baldet, Jordan Barbour, Kyle Beltran, Cindy Cheung, Irene Lucio, April Matthis, Grace McLean, Jennifer Morris, Tanis Parenteau, Monica Salazar and Rona Siddiqui. The piece featured songs by Maggie-Kate Coleman and Erato A. Kremmyda, Grace McLean, Lady Rizo and Yair Evnine, Kirsten Childs, Michael Friedman, Rona Siddiqui and Ty Defoe.