January used to be the dark month, where shows rarely opened and artists hunkered down to make new work to bloom in spring and run the summer festival circuits. But over the past several years, the new year in New York became known for hosting fresh, innovative theater and performance art from around the world.

PS122’s COIL is a celebration of such performance. Featuring multimedia, dance, interview-based, and solo theater, the festival is one of the main events surrounding the annual hubbub of APAP (Association of Performing Arts Presenters). Extended Play writers Cory Tamler, James Carter and Tommy O’Malley spoke to the creators of three COIL shows about their journeys to this hot winter festival.

Tamler, who is currently working as the New Museum’s Spring 2016 R&D Season Fellow, has been conducting a series of in-depth interviews with the museum’s resident artists and affiliates. She shared some takeaways from her time with Michael Kliën and Steve Valk, the creators of “Excavation Site: Martha Graham U.S.A.,” a one-time only event co-presented with New Museum and Martha Graham Dance Company, which will take place on January 16 at Martha Graham Studios.

In the realm of interview-based theater, Carter sat down with Adriano Cortese, the director and one of the creators of “Intimacy,” by the Melbourne-based Ranters Theatre, which runs January 11-16 at the New Ohio Theater.

And O’Malley spoke with writer/performer Chris Thorpe about his solo show which explores the phenomenon of “confirmation bias” in “Confirmation” running January 13-17 at the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn.

EXCAVATION SITE: MARTHA GRAHAM U.S.A.

by Cory Tamler

Initial conversations between choreographer Michael Kliën and dramaturg Steve Valk, who work together as a team to create social choreographic situations, and Janet Eilber, artistic director of the Martha Graham Dance Company, happened two years ago. Eilber wanted Kliën to choreograph for the Company, but it turns out that commissioning a work of social choreography is no speedy or straightforward process.

The first major intervention to emerge from the dialogue, “Excavation Site: Martha Graham U.S.A.,” is taking place on January 16, 2016, in the Martha Graham Dance Studios. Part dance performance, part salon, part tea party in your smart friend’s living room, the four-hour event (come when you want, leave when it pleases you) aims to productively shake the foundations of the Graham Company as an institutional construct. At the same time, everyone in the room will become part of an attempt to expose — and disrupt — societal constructs that shape our collective reality.

Kliën told me that “Excavation Site” is “not just a title for this work; it’s a way to describe my methodology as a choreographer, creating realms in which you can experience your own situatedness, vis-à-vis the other, and with yourself.” Where traditional choreography consists of building (Kliën likens it to snapping Lego blocks together according to a specific set of rules), an excavation site starts with digging.

This digging takes many forms. As the incoming R&D Season Fellow at the New Museum, which is co-presenting “Excavation Site: Martha Graham U.S.A.” with Performance Space 122 as part of the COIL 2016 Festival, I am one of the newest pair of hands working on the project, and I am uncovering many ways that the metaphor of excavation has shaped it. Here are a few such examples, presented in Kliën and Valk’s words.

“Excavation Site: Martha Graham U.S.A” company. Photo Credit: Brigid Pierce.

Digging up Martha Graham

VALK: The Warholian image of Martha Graham has replaced the reality of the thinker and artist that she really was. That’s part of the Graham legacy we feel naturally connected to. The whole event is about digging down beneath the persona and the artist “Martha Graham” to the kind of ore that she might have been mining in her own work.

Exposing Invisible Structures

KLIËN: I would like to think that a different choreographic relationship to your surroundings would help to school your perception to see, and to feel. Not just to see in the visual sense or understand in the cognitive, rational sense, but actually to feel the fluidity of the constructs all around us.

VALK: You try to get your surroundings to sense that they are creating containers. And that they are actually choreographers. And that the world is a choreographic situation.

Laying a Foundation

VALK: It’s an insane period of time, two years, to do this thing. But maybe this is the kind of work that has to happen to establish this new field [of social choreography]. It’s like you’re digging a hole for one column in a building and you only have spoons to do it. Because there are no tools. So you decide to dig anyway, and [after two years] you’ve got one part of a giant building. One hole for the first pillar to go into.

Burrowing into Institutions

KLIËN: How much can this project contribute to releasing some of the tension within an institution? Choreography is a temporary stable pattern. But also a company is a temporary stable pattern. And at some point it will die. That’s not bad. Because hopefully it will have offspring that will maintain life, as they say, on the lips of the living. But if it becomes afraid of its own death, it uses tools that are unacceptable to maintain itself.

Excavating Possible Futures

KLIËN: If Graham’s movement “built,” in the sense of ideologically encoded and propagated, the modern United States, how does it have to move now to respond to the monster it has created? How to move now? As an institution, as individuals, as a group. This is the key question.

INTIMACY

by James Carter

(The original interview has been edited for space.)

Patrick Moffatt with the “Intimacy” cast. Photo Credit: Maria Baranova.

JAMES CARTER: Tell me a little bit about the show.

ADRIANO CORTESE: It started when we were sitting around discussing what we were going to do for the next show, trying to come up with an idea. I was recounting this story about how I, one night, when I lived above a shop on quite a busy street, and I was with a friend of mine. We were just having a couple drinks in our apartment, and we thought, “Why don’t we just go down to the street and get a whole bunch of strangers off the street and just bring them up to the flat and have a bit of a party?”

So we went down to the street, and that’s what we did. We just asked people. We said, “You know, we’re having some…do you mind coming up?” A lot of people said, “no,” obviously, but quite a few people said, “Yeah! Okay. Sure.” So we got up a bunch of people. Nobody knew each other. And there was a guy who was, like, busking with a piano accordion. We gave the guy, like fifty bucks to come up, and so he had this piano accordion playing. But very quickly what happened was that people were just talking — complete strangers — and just, sort of, started being very personal. Very personal conversations very quickly.

So I was recounting this story, and so then we decided to: why don’t we just…make something about encounters that we’ve had with strangers? And we just started telling each other some of the things, some of the conversations we had with strangers on the street. We went out and sort of had a couple more. And then we brought that material onto the floor, and we started just improvising with it. And then we started pulling our own stuff in as well. So we mixed it all up, and that’s how we created the show.

JAMES: Did you ever record the conversations?

ADRIANO: No.

JAMES: How much of it would you say is source material?

ADRIANO: I would say, like, seventy percent of it is source material. I mean, it’s not word for word, but the story that I got of this particular character – what he does, what he says, what he told me in the conversation — is kind of like…is pretty much all true. But the details have always kind of changed. Then, as I say, we started filtering in other little bits in because it’s all very personal and intimate. We started to filter in our own lives.

JAMES: So it’s a mash up.

ADRIANO: Yeah.

JAMES: Who did you speak with?

ADRIANO: One was based on a conversation that one of the performers had with a pilot, who was incredibly drunk who had panic attacks.

JAMES: (laughing) Oh, Jesus.

ADRIANO: So the audience sees the scenes but they don’t say, “Oh, that’s that guy, or that’s that guy.” We just perform them ourselves. We don’t work with character or anything like that. We do them all as ourselves. We called it “Intimacy” because the conversations were intimate but we also wanted to have intimate experience with each other and also the audience.

JAMES: I know the performances have been lauded for their naturalism. Are you taking those characters and being yourselves, essentially?

ADRIANO: Yes. We talk them as ourselves. We just talk like we’re talking now. But we do different things. Like the first one is just a conversation on two stools. But then one of the other performers just gets up and stands next to him and starts going like this, and he goes, “So I just stand in front of a department store, and I do something like that.”

(Adriano stands and makes a gentle fluid movement.)

Intimacy Teaser from Performance Space 122 on Vimeo.

So it’s the same feel for us. We do it in the same way. If it were me, I would do it like that. But because it is very different than having a conversation, it’s saying it appears to other people like we’re a different character. I guess. That’s how some people have said it. But we do it very simply. We don’t sort of suddenly create anything other than ourselves.

JAMES: And did that intention come out of rehearsal?

ADRIANO: We’ve always been interested in performing like that. So we tend to do that, generally, no matter what we’re doing. No matter how extreme physically we are. We always do it like that.

JAMES: How does the video play into it?

ADRIANO: We’re just interested in this blur between fiction and non-fiction. So when the scene starts, we have a video portrait of one of the performers at the same time. So you see him on stage, and you see him up close, quite up close. It’s not a still. It’s a video. Originally, we had the name of the performer — like the pilot, such-and-such — but we took that out because we realized we didn’t need it. It probably raises more questions for the audience…but we tend to like it like that.

JAMES: How long has your core group of actors worked together?

ADRIANO: We started in ’94.

JAMES: Over 20 years.

ADRIANO: But we don’t work that often. We’re not hugely prolific. A lot of us do other stuff. We just get together every couple of years or so. I think we’ve done about 15 shows during that time.

JAMES: How long have you been doing “Intimacy?”

ADRIANO: Since 2010.

JAMES: How has it changed over six years?

ADRIANO: Well, we haven’t been performing it for “six years.”

JAMES: Right, right. So how does it change when you revisit it?

ADRIANO: It changes quite a lot. Because our work is very much about making like you’re really having a conversation. That always changes things because we’ve changed a little bit. We’ve changed the tones of things, or changed some words. It’s not improvised, but the feel of it is very improvised. And so when we’re talking things will shift around. From when we first did it, we cut quite a bit.

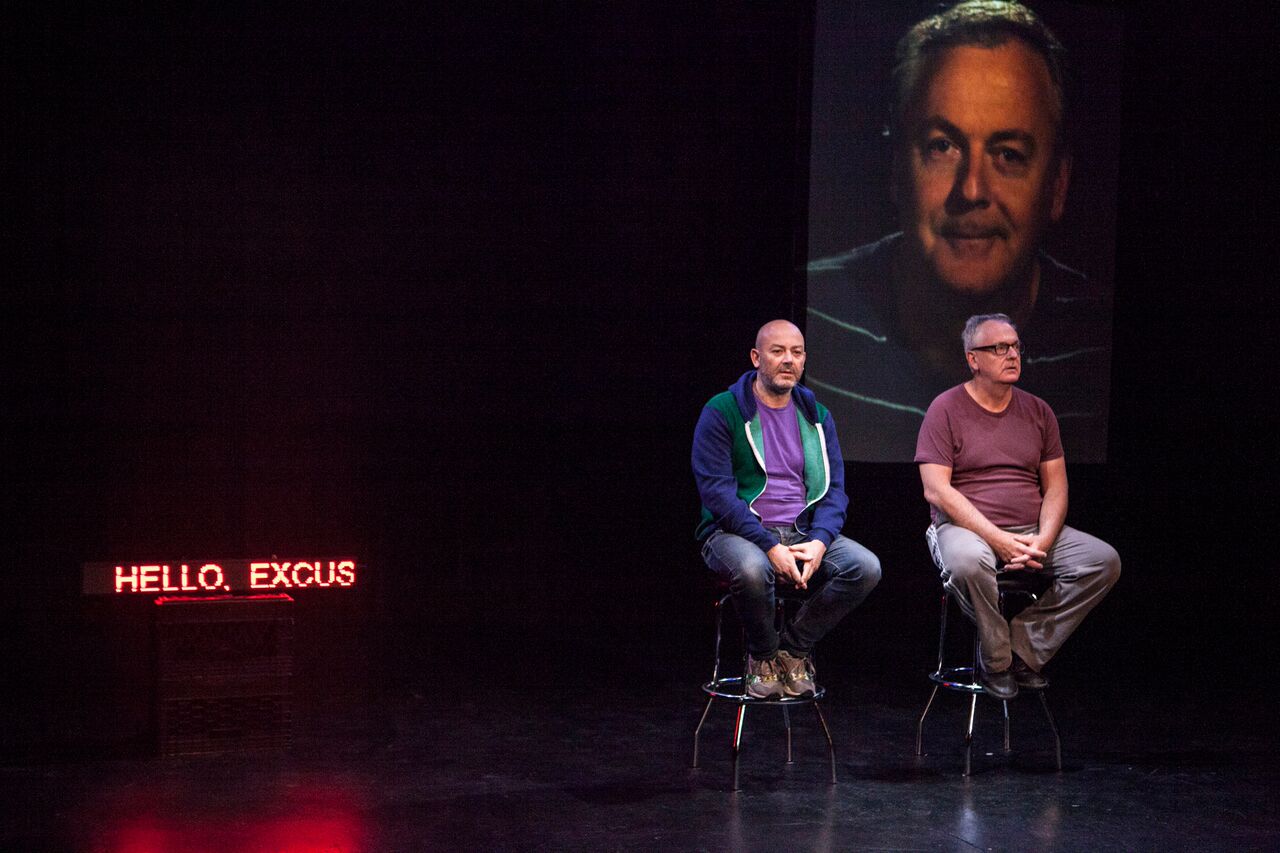

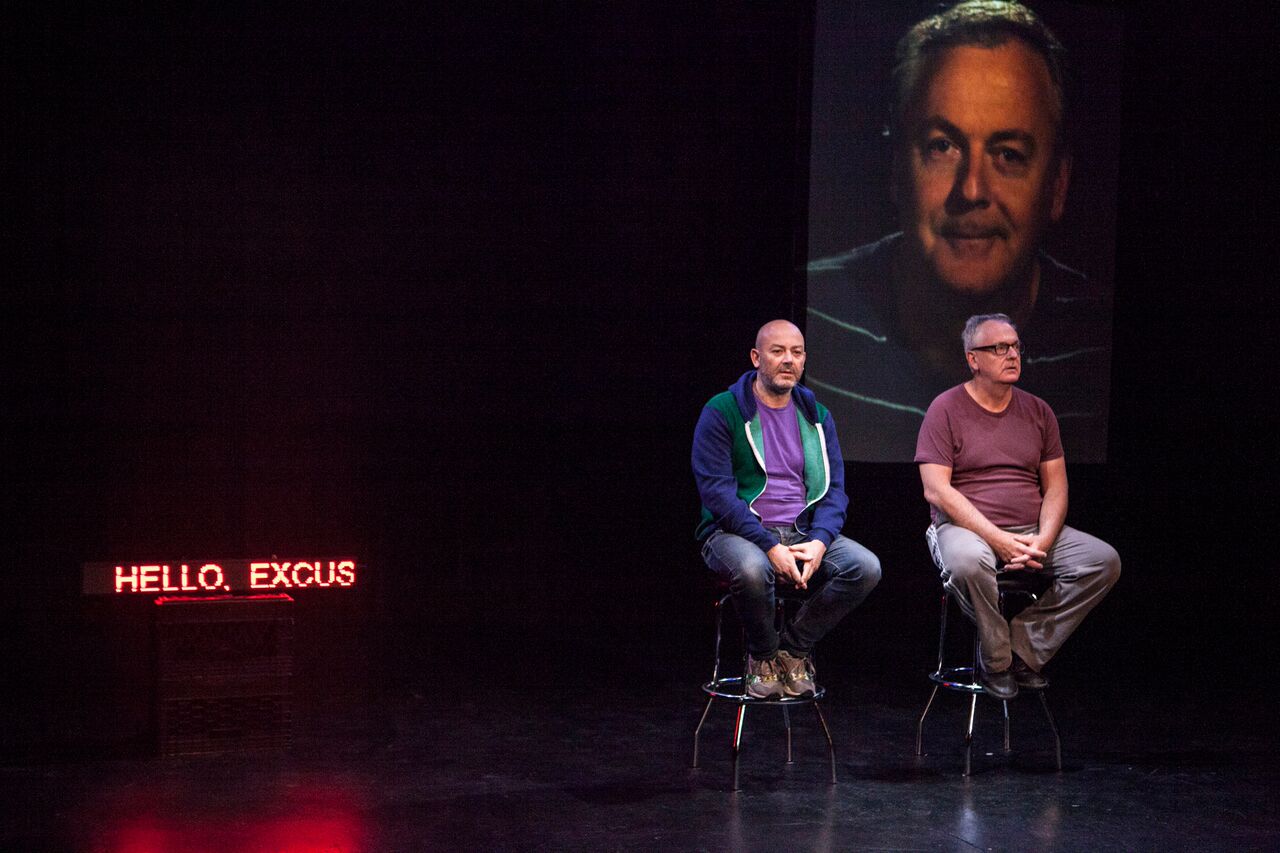

Adriano Cortese (l) in “Intimacy.” Photo Credit: Maria Baranova.

JAMES: Do you find that enjoyable to go back and revisit?

ADRIANO: The most enjoyable thing. Yeah. The most enjoyable thing is to be playing around with it. Playing around or discovering new things. For me.

JAMES: What’s most enjoyable about it?

ADRIANO: When it touches your life, I guess. Often a change comes about because something shifted in you, and you realize that. You know? Something I remember in this rehearsal. I don’t remember what the bit was, but I remember the feeling going, “God, so that’s what that is! Oh, my God I haven’t really, sort of, you know? That’s pretty — sad?” Things like that. Just little subtle things will change. Being in front of an audience is great, but it’s never as much fun for me — and this might be because I’m the director — as when you’re working.

CONFIRMATION

by Tommy O’Malley

(The original interview has been edited for space.)

Chris Thorpe in “Confirmation.” Photo Credit: Arnon Friess.

TOMMY O’MALLEY: I would love to hear about “Confirmation.” The description on the COIL website is sort of delightfully ambiguous, just talking about extremism. And I don’t know what that means, so I’d love to know what you think that means and why you’re exploring it.

CHRIS THORPE: Well I think that description probably is trying to navigate between different definitions of extremism, if you’re from the U.S. or the U.K., without trying to create a highly localized perception of what it is. So for me, I got really interested in confirmation bias and this propensity we all have, when we ever see new things in the world — the world being media, being our personal interactions, being just our observations of the reality around us — we’re only seeing the things that confirm the points of view we hold already, that agree with the reality we’ve constructed in our head. So I had this idea about talking to someone who was on paper really similar to me. So a guy, a white guy, a British white guy, a British white guy of my, if you like, background — and that’s my ethnic background, my socioeconomic background, from the same kind of community as me. But we both held very different views. And when he looked to the world, unconsciously cherry picked very different aspects of it to me, in order to bolster a different set of beliefs. So the show was basically about me testing my own confirmation bias initially, but through a series of conversations I’ve had over a year and a bit with a guy who identified as a national socialist — a Nazi — with all the racial and historical beliefs that that involved. And to see if we could have this honorable dialogue, to see if he and I could sit down and respect each other’s viewpoints to the extent that we could get an insight into how each other thought.

Confirmation Teaser from Performance Space 122 on Vimeo.

TOMMY: How did you connect with him?

CHRIS: I started going to meetings of fringe political parties that held what would be considered extreme racial or social views. And I thought that’s where I would find my guy. And I didn’t. So I spent a lot of time with classically extremist political groups, and I found that, because they were politically engaged, it was hard to talk to the people who would’ve been useful to talk to, because they were too guarded. They have this set of political priorities that involve them gaining power in the system. And the people who are less involved in those groups, in the active process of getting into that system, were generally damaged in a way that would’ve made it unfair to make them the subject of the dialogue. I’m not saying they weren’t intellectually capable. I’m just saying they needed different things out of life than to be talking to me. So I physically went out and met these people, went to their meetings. I was very open about who I was and what I was doing when I was asked, which made for some awkward situations. But I didn’t find anyone there, and eventually, at the point of giving up, I found this guy’s website, which is actually fairly popular — a frighteningly popular white supremacist website — where he writes with great intelligence and erudition, at least in the way that he constructs his language. And I emailed him and said, “Listen, this is what I want to do. A, do you want to talk to me? And, B, what would be the conditions you would want to put on this conversation?” He came straight back to me. He sent me back pictures of myself, because he’d done his research. He said, “Is this you? What you do looks interesting.” Which was a bit of a fucking shock to the system to start with, because you expect to dismissed by “these people” as some kind of liberal arts dilettante or whatever. And he came back, and we started a dialogue, and we did it on condition of anonymity, but we also did it on condition of honesty. So I found him with that kind of Hail Mary, last throw of the ball, after I’d failed to find him in any of the places that were expected.

TOMMY: So “Confirmation” is a one man show based on your dialogue with this National Socialist, this Nazi. Is the show verbatim?

CHRIS: It’s not a verbatim show in the sense that it recreates those dialogues. It’s just me on stage, but certainly there’s an element of getting across what was actually said between us. But it’s also a show that’s about the effect that had on me and my own sense of myself, because our personalities are created in part through these biases, and when you start to destabilize them, you start to fall apart in interesting ways. Also, because I’m acting in it, it’s about that ambiguity in the room where, at points, you’re not sure which one of us is speaking…and how that destabilizes, perhaps for the audience, the experience in the moment of what they’re seeing, and what they are picking out, and what they’re seeing to confirm their own world view. And it’s kind of about how that was a tremendously destabilizing thing for me, in terms of the way that I view myself, but also in terms of the way that I view people who hold, quote, “those kind of views,” because obviously there’s a lot more “oh fuck” than we generally allow ourselves to believe between us and whoever, from our vantage point, would be an extremist.

TOMMY: What’s the “oh fuck” you’re talking about? Is it the, “Oh, I maybe agree with this?” Or, “Oh, maybe I’m more ideologically aligned than I would like to admit?” Or is it, “Oh, fuck that’s crazy?”

CHRIS: There’s a combination of “oh fucks” in it. For me, it’s a whole series of “oh fucks.” Those “oh fucks” you’ve identified are all certainly represented in the show. There’s a personal “oh fuck,” I guess, which is, “I am maybe not the open liberal that I thought I was.” The one “oh fuck” that isn’t in the show is, “Oh, fuck. I’m actually a Nazi now.” There are no spoilers here. This is not a show about my conversion to National Socialism. But it is certainly a show which has the “oh fuck” of, “I cannot now dismiss this philosophy as simply and easily as I would want to, because oh fuck, we are not in any way as other to each other as I thought we were. And it’s, oh fuck, maybe, given that I have this propensity to dismiss those people as unthinking bigots, actually which one of the people in this conversation is being intellectually lazy. And, oh fuck, reasonable tone of voice is not necessarily any guarantee of reasonable point of view. And these are quite obvious “oh fucks.” But when you’re in the middle of them, and certainly when the show does that, I think they’re destabilizing. And there’s certainly the “oh fuck” of, “Jesus Christ, what is this guy saying?” And that’s an “oh fuck” I live through every time I do the show.

Post Views:

1,223