Jason Grote is a playwright well-versed in many modes of dramatic storytelling. His plays often riff on familiar theatrical forms — such as the family drama or the folktale storybook — blending trenchant political allegory with fanciful, otherworldly elements. He has written for a range of television shows, including “Mad Men,” “Hannibal,” and “Smash.”

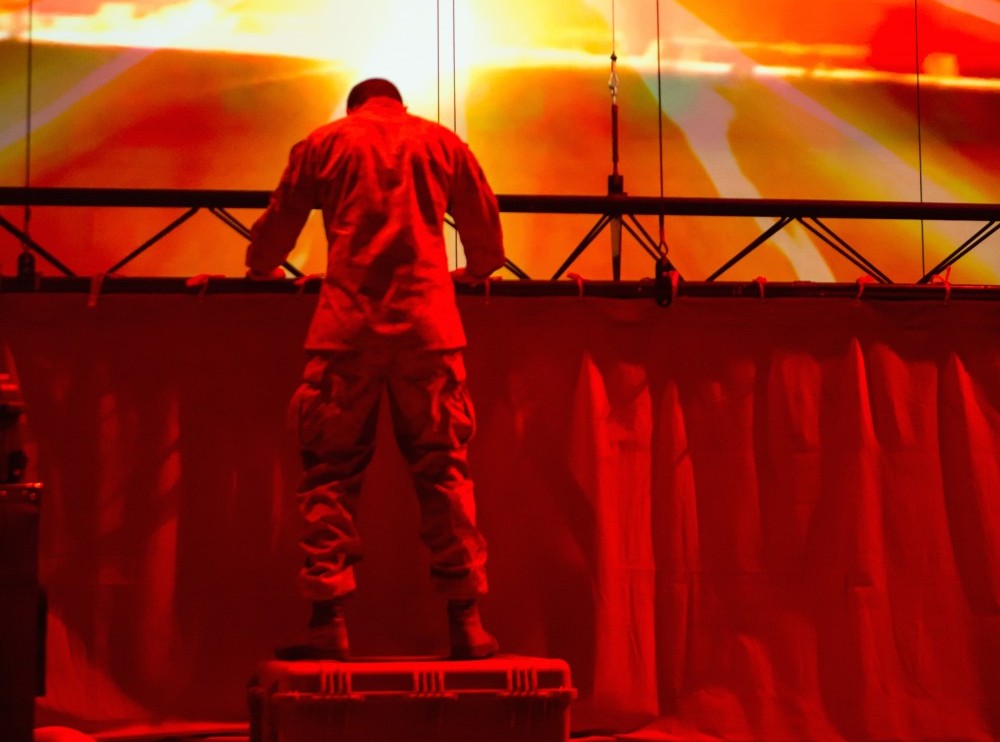

Recently, Jason collaborated with “BASETRACK Live,” a Facebook group that has born a multi-media documentary about journalists and Marines returning from Afghanistan. The piece — which played the BAM Next Wave Festival in November 2014 — features photographs and videos from journalists embedded in Afghanistan, interviews with Marines and their families, and music by Edward Bilous and Michelle Dibucci. Extended Play Editorial Associate Elliot B. Quick talked to Jason about how he used the considerable source material to tease out the scripted elements of “BASETRACK Live.”

JASON GROTE: “BASETRACK” was originally a sort of web-based journalism that, on its own, mutated into a community. It was this guy, Teru Kuwayama, and a couple of other photographers who had embedded themselves with the One-Eight, a marine unit in Afghanistan, and they couldn’t find a news organization that was willing to publish their photos. So they wound up just putting it up on the web themselves. And then the Facebook group for the website — a lot of the families began contacting each other or asking some of the other journalists for information that they couldn’t get from the military. It was serving a purpose for the military, but sometimes the military wanted it there, and sometimes they shut it down for security concerns and things like that.

Ed Bilous, who did the projections, and his wife, Michelle Dibucci, a composer — they created a chamber music piece that used these photographs as video projections. And Anne Hamburger, the producer, saw this and said, “This needs to be a piece of theater.” That was the origin of it.

I was brought on by the director, Seth Bockley, to come up with a text — to figure out how to make it into a story. And we went back and forth in a lot of different ways. One of the big challenges was that none of the Marines themselves were posting on the Facebook page. They actually wanted to isolate and control their communications home because it turns out that that is a pretty major contributing factor to post-traumatic stress. There’s this statistic that drone pilots have higher rates of PTSD than deployed soldiers do, because of the constant moving back and forth from combat life to regular civilian life. It was something that even the Marines that I spoke to that didn’t have post-traumatic stress still struggled with. It was really difficult to go back and forth to this place where all you’re basically worried about is following orders, and combat survival, and doing this mission that you’ve been extensively trained to do, but you don’t have to worry about all the minutia of daily life. And then coming back and constantly having to adjust to a non-combat situation.

Anyway, we had like 1,000 pages of Facebook posts, some of which were really interesting. But I realized pretty quickly you couldn’t make a play out of this unless you were doing something that was really aggressively avant garde. It wouldn’t really be about the Marines and their families; it would be about people speaking Facebook posts, which was not really what the show was designed to be.

I wanted to do this because “BASETRACK” didn’t really have the perspective of a lot of the Marines themselves, and didn’t really tell the other side of the story: drawdowns from the Afghan war had begun in 2011, so when we’re working on this in 2013 and 2014, we had a couple of years of the aftermath.

I had done the Civilians’ R&D lab and a few dozen workshops about interview techniques, which was actually very useful. I didn’t have the time to get to know the interview subjects all that well, but it was a good training for how to sit back and let the interview subject lead the way, and not be too leading or let one’s own perspective interfere too much.

The interview subject that jumped out at me was a marine named AJ Czubai. He became the protagonist of the show. I had about four phone conversations with him, and there were so many interesting details about his life. I think that what I wanted was somebody that would be unique enough to tell an idiosyncratic, individual story, and not just be a generalized wash, but also somebody whose experience more or less mirrored that of many Marines or just-returning service personnel. So there were certain details: the fact that when he was in high school he lived in Germany for a few years and did school in German; that he played the euphonium, which is sort of a miniature tuba; that he had a favorite composer, Stravinsky; that he grew up between Texas and Virginia. All these details about his life made him really fascinating to me. I actually spoke to his mother and sister a lot, too, which didn’t make it into the show. And I spoke to his current girlfriend, which also didn’t make it. And then his ex-wife.

I went down to Austin to video him with a student video crew. It wasn’t really the documentary quality footage of the other stuff that’s in the show, but I went with a crew and I got to just see the guy, and meet him, and see his home. And then his ex-wife Melissa—we had spoken on the phone a few times, and she wasn’t sure until I was actually down there in Austin for a weekend that she was ready to talk to me. She called up and was like, “Okay, I’ll definitely do it.” I was just with my phone. I didn’t really have any equipment with me. I just drove 45 minutes to this apartment complex that she manages, and I talked to her for a while.

Pretty much the show is verbatim, but I would sometime weave together phone conversations and spoken conversations, and jump back and forth between them. And I played with time a little bit to try to weave it into a coherent narrative. Eventually I handed the thing over to Seth because I think the show lives as a music and multimedia piece as much as a piece of scripted theater.

ELLIOT B. QUICK: “BASETRACK” moves back and forth dynamically between live actors and projected interview footage. Can you talk about how you conceived of those two different modes of presentation?

JASON: The process for me was I originally I put in big blocks of text that I knew would just be our video subjects. I was present for a lot of the interviews that wound up projected onto that screen, so I would pop them into the script. And then I took them out of the script to focus on AJ and Melissa. And then I tried putting them back in. Video projections are so fundamentally different from hearing a live actor’s voice that I felt that it had to be part of the tech. It all had to happen at once.

Projections in theater are a design element. The difference between watching a movie and a play — your attention when you’re watching a live person talk can be sustained for a lot longer. The Civilians does this a lot. They use intercutting between monologues that creates ironic juxtapositions, and changes rhythm, and finds unintended moments of humor.

With film everybody knows this vocabulary, and in a documentary you can listen to a person talk for a while, but then you’re also cutting away to a different angle. Or you’re hearing their voice, but you’re seeing something different visually. I think that it’s extraordinarily difficult to listen to a single person in a static image talk for ten minutes on film. On stage you can do that. It’s a different kind of attention.

ELLIOT: How does the music in “BASETRACK” fit in with that?

JASON: It began as a piece of music. And even though Ed and Michelle were extraordinarily collaborative and very welcoming to making all voices equal, their music couldn’t become underscoring because the music came first. So I couldn’t write it as if it was just a play that would be underscored by music. I was writing it almost as a separate element to be integrated later. And my idea was always to hand it over to Seth. Somebody has to be the arbiter. It’s not the traditional form of playmaking where you write a script and then you hand it over to a director and cast and designers who execute that script. The creation of it is all happening at once.

ELLIOT: When you’ve written in that more traditional form of playmaking, you often incorporate wildly imaginative and fantastical elements: the mythic fantasies in “1001,” the shapeshifter in “Maria/Stuart.” When you’re working with something that is so much based in interview material and real facts of the world, are you exercising different muscles as a writer?

JASON: I think so. Part of the challenge and what was exciting to me about this project was the act of taking myself out of it. Of using my instincts for narrative. In a way it was more like what I do when I write for TV, in both the collaborative nature of it, but also in terms of getting out of my own way. The show doesn’t really reflect this, but I’m extremely anti-war. I’m not necessarily a pacifist, but I’m one of the people that’s so far to the left that I wasn’t even in favor of the war in Afghanistan. And that was a challenge.

A lot of people did talk to us to ask, “Well, where are the voices of the Afghans?” I wouldn’t even know how to begin to get those voices. My suggestion to someone at the TCG conference was to put “BASETRACK” in repertory with “Aftermath” [Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen’s 2009 docudrama generated from interviews with Iraqi refugees living in Jordan]. Have a double bill that shows the impact of war on different sides. I think that’s a legitimate criticism of the piece, but I also think that it should be about what it’s about. I wanted to keep it about the affect of war on these people. And that’s it. Let them tell their story. Because I have my own set of assumptions, but by backing out of it and not making as much of a commentary…

The places that I went — I went to extremely rural, conservative South Carolina. I don’t necessarily like to get sentimental and sappy about creating dialogues between liberals and conservatives. I’m not really concerned about that. But I think that when you can take a lot of the rhetoric out and concentrate on the lived physical experience, there is a lot of agreement. That was part of the challenge too. We wanted to make something that belonged in the BAM Next Wave Festival, that didn’t compromise, that didn’t aim itself at too broad of an audience, but also something that veterans and their families could come to and not feel stupid because they hadn’t seen a Robert Wilson play. And that was a challenge that I think we pulled off — something that actually would appeal to an audience that just doesn’t go to theater, that doesn’t think of theater as “for them.” To do that without aiming too low, or without making it too broad, or too sentimental. I do think that we achieved that.

“…when you can take a lot of the rhetoric out and concentrate on the lived physical experience, there is a lot of agreement.”

ELLIOT: Where else is the show going? Is it being put in front of audiences different those that find it at the Next Wave Festival in Brooklyn?

JASON: The BAM thing was a culmination of a long tour. It went to a lot of college performance venues. I’ve only seen it in LA at Royce Hall, because I live here, and then at BAM. I know that it did have lots of audiences of veterans and their families. It had runs in Kansas and Kentucky, Virginia, Florida, Texas. It was at college campuses and cities, so I’m sure a good portion of the audience are the people that go see all the touring shows that come to those venues. Anne Hamburger worked really hard with veterans organizations to get people to go there. There are a lot of “veterans in the arts” groups. But the population in a lot of these places — they’re not the people that are going to get a subscription to see Elevator Repair Service come through. So that did take a lot of work, and I think that it was sometimes successful. I think that she has hopes that she’ll find a place to put it — either bring it to military bases or put it in a museum. That’s what En Garde Arts does: nontraditional spaces. So, for instance, she can put it in the Intrepid Museum. I think that that would be great.

Jason Grote’s plays include “1001,” “Maria/Stuart,” “Civilization,” and “Shostakovich.” He wrote the script for David Levine’s OBIE-winning “HABIT.” Current projects include a play for Radiohole, a commission from Soho Rep, and a film adaptation of John Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother” for Water’s Edge Productions. TV writing credits include “Mad Men,” “Hannibal,” “Smash,” “Lizzie Borden: The Fall River Chronicles,”and “Rogue.” He teaches at UC San Diego and was a member of the Civilians’ R&D Lab from 2010-12. He is an alumnus of New Dramatists.

Jason Grote’s plays include “1001,” “Maria/Stuart,” “Civilization,” and “Shostakovich.” He wrote the script for David Levine’s OBIE-winning “HABIT.” Current projects include a play for Radiohole, a commission from Soho Rep, and a film adaptation of John Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother” for Water’s Edge Productions. TV writing credits include “Mad Men,” “Hannibal,” “Smash,” “Lizzie Borden: The Fall River Chronicles,”and “Rogue.” He teaches at UC San Diego and was a member of the Civilians’ R&D Lab from 2010-12. He is an alumnus of New Dramatists.

Author

-

Elliot B. Quick is a dramaturg, writer, producer and teacher based in Brooklyn. He received an MFA in Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism from the Yale School of Drama, where he was the Resident Dramaturg and Associate Artistic Director for the 2011 Yale Summer Cabaret Shakespeare Festival and the Associate Artistic Director for the Yale Cabaret's 43rd Season. Elliot has previously served as a Literary Associate for Playwrights Horizons, Yale Rep and Page 73. He works regularly as a freelance dramaturg, teaches Theater History at the Maggie Flanigan Studio, and is a founding member of the inter-disciplinary performance ensemble Piehole. He is the former Editorial Associate at the Civilians.

View all posts