In their new blogcast, R&D Group members Galia Backal and Noelle Viñas sit down with dramaturg Dante Flores to discuss their play, El Cóndor Mágico, inspired by Operation Condor, the US-backed campaign of right-wing dictatorships and repressive regimes in South America throughout the 1970s-80s. Listen to their conversation above, or read the full transcript of the podcast below.

Galia Backal: Hi, everyone. Welcome to the Extended Play blogcast for The Civilians R&D Development Group. We are the Operation Condor team. My name is Galia Backal and I am the director of El Cóndor Mágico and I am on Munsee Lenape land.

Noelle Viñas: Hi, I’m Noelle Viñas and I am the playwright of El Cóndor Mágico and I am on Munsee Lenape and Canarsie land.

Dante Flores: Hi, I’m Dante Flores. I’m the dramaturg and I am on Wichita and Caddo Land.

Galia: and we’re excited to welcome you all into our world, into our development process today. And we were thinking about how we wanted to lead this, what we wanted to talk about, and we decided to really base it off of what we have been exploring in the piece. First, I’m going to throw it over to Noelle to tell you what this piece is.

Noelle: Yeah. So for those of you tuning in, this is El Cóndor Mágico – is basically a story that follows Nieta, which means granddaughter in Spanish, as she kind of after the death of her father, where she starts kind of uncovering a lot of family history that is both known and unknown to her. And that I mean specifically that it is kind of on a subconscious level that, like, her family lived through a dictatorship. And it has been mentioned quite a bit. But she has never really fully explored as an adult the themes and kind of generational trauma that comes of living through a dictatorship and what that means to her as someone who is now a dual citizen living in the US, which historically helped and aided and abetted the dictatorship in her home country. So it’s kind of an exploration of family history, using ghosts, using kind of the tropes of magical realism and kind of winking at them and kind of using them in the way I think they’re meant to be used, which is kind of as a tool of political criticism and kind of symbolism instead of kind of being like “we’re magical and realistic and we’re Latinx,” it it really tries to serve them as a political tool, which is what I think they’re meant to be.

Galia: Yeah, what you already touched upon: The thing we’re really diving deep into, which is the magical realism, the storytelling of the ghost that this-this journey has created. And I think for all of us, we’ve all discussed how our own family history has been brought up through storytelling, through ghosts, especially in Latinx culture, how important that is. So I’d love to hear all of our thoughts on how the piece has brought that up, how we also explore our own stories in those ways.

Noelle: Well, I guess I can jump in and just say that the piece is very much partially based on my on my family history in a very direct way — like, it doesn’t even try to hide very much that that is true. So I think there’s a big sense of, at least in my family and in the culture that I have, of stories that get repeated time and time again and again, kind of how those that repetition of those stories changes each time. And then there’s also like — because the stories get repeated, you often miss an important detail that would that logically, if you were outside of the family unit, you’d be like, wait a second, why is that a theme? Like how did they end up working at this factory or why did they end up having this thing? But you’re part of the family, so you just hear that repeated story and you do the same logic jumps every time. So, yeah, I don’t know if that’s quite answering your question, Galia, but that’s something that’s come up a lot for me as I’m kind of exploring family stories: is like talking to other creators and storytellers about family stories is, like, also witnessing the logic jumps that you make in repetition, you know.

Galia: Yeah, I think it is definitely logic isn’t involved, especially what you’re talking about, ghosts or brujeria and those kinds of storytelling aspects, I think I accepted long ago that they’re just things my family will say about the ghost, like, oh, you have to stick a knife in the ground to pay respects so that the storm doesn’t pass. And that’s just how it is. You don’t question that idea. In my family, we’ve always had ghosts present, I think like a very specific to Mexico because we have Día de Muertos. We don’t believe that ghosts ever leave us. They’re always here and watching over us. So they they’ve been used as a way of storytelling as but also as a way to put, push and pull down on these family values and morals, which I think is really interesting. And I think that that comes through in the piece as well of the the stories and those ghosts and those people being used as a ‘that’s how it is’ or ‘that’s how the world will be.’

Noelle: Yeah, I think that’s probably accurate. I feel… I feel like on another level, there is kind of like in the way that you were talking about, like always sitting with ghosts and always thinking that ghosts exist. I think one of the things that I can say… I hesitate these days to broadly say that all Latinx people do anything because we’re not a monolith, y’all! But also I feel really strongly that, like one trend that I feel like I usually encounter is that Latinx folks are really comfortable and open to talk in most cases about their grief and about their loved ones, as if they’re sitting with them all the time because there’s a real sense of like spirituality and it’s like a very normal thing after someone passes to speak while they’re still here, you know, like so I think that that’s like — they’re still with you! They’re totally in you and hanging out like, you know. So… I think that that’s a very real celebratory way of dealing with grief that I think I could I venture to generalize is the thing. Yeah. I don’t know. I’m curious Dante what your experiences with your family. I don’t think we’ve ever talked about it.

Dante: Yeah I haven’t spoken a lot about it during our meetings before. I agree that I do think, you know, it’s it and it’s an accepted convention… not a convention. But like, it’s an accepted thing in my family, too, right – like, somehow every house we’ve lived in is haunted. And and I think I think it does go to this very Latinx of just being very open about grief and death and passing and loss and all of those things. Right. It’s but, you know, my aunt my aunt passed away about last year, about a year ago or so. And she loved birdwatching. And one of her favorite things to do, like she had binoculars and a camera and all that she had, like all the equipment to do it. And recently we’ve started putting, like, you know, we started seeing, like, birds outside of our houses and stuff like outside of our house and stuff. And we see it more and more lately and more different kinds of birds like cardinals, blue jays, mourning doves, robins, things like that. Right. And. I know that for me, it’s kind of been a way of like watching these birds as they pass by. It’s it’s been a way of like. Not grieving because I don’t feel I don’t feel depressed about her loss, I don’t obviously like yeah, there’s a sadness there that she’s not physically there in the room with us currently, but there’s an at peaceness I think it’s watching a bird becomes this meditative thing suddenly. And it’s a meditative thing like in her memory. Right. I don’t know if that makes any sense. Yeah, but, yeah, also it’s. There are also like stories about former or like family members, ancestors and stuff who fought in the revolution and were like on the run from the Profiriato of the US government or like got in trouble with U.S. marshals. And like all of which was because there were like newspaper publishers who were like writing about labor conditions on the border or something. Right. Like people who were even running guns or something for the División del Norte. So like, yeah, it’s crazy, crazy stuff. And all that stuff gets passed down. Right? Like there are some family members keep records of this stuff. So you send them a message on Facebook or something like tell me about Uncle Daniel all those years ago. Yeah, it stays in the family and all that stuff, just kind of like kind of disseminates like osmotically between members of family.

Galia: Yeah, but the birdwatching story hit me so hard because I think we all have the different version of that story, right. I had a similar moment where when my abuelo passed, he, I think a year before had given us this, like, old stumpy route. We didn’t even know what it was. We’re like, this is an ugly route that you planted the garden and it’s going to be fine. And we planted it, it did nothing. And it just kept like looking like this ugly stump in our garden. And the morning he passed, it began blossoming cherry blossoms. And ever since I’ve only like I can’t – cherry blossom season for me is like a whole. It’s a moment of remembrance and feeling his spirit with me and knowing that, like new life blooms. I mean, it’s not to say that, like, we all we don’t grieve as Latinx people. I think it’s like this weird hand in hand that we know that they’re still here. So there’s something comforting about that. And so it becomes more celebrating their life versus grieving that they’re not here, which is something I feel like I’ve taken for granted in the past. And recently, of course, because of the pandemic and just the state of the world, I have realized that that was such a gift

Noelle: Because it helps you move through things. I mean, I can share – like my, my abuelo passed, like it’s been like 14 days. No, even less, it’s been like 12 days. And he’s very much the center of this piece, which is in a big way. And so I think that there’s something really interesting and like I think and we had no kind of warning that he was going to pass, although he was older and he just kind of died in his sleep, just kind of really casual, really best way to go. But but what’s really fascinating is that I do think that there is kind of like a happy circumstance, at least for me, and like working on a piece that very much evokes him. And also, like in that connectedness of feeling spiritual and feeling the supernatural, like I sent him a text the night before, like he was like on my mind. And it’s not because I text him every day. I text him like probably three times a month and, you know, out of respect for our various schedules. And so it’s it’s very interesting to have these moments where you feel kind of this heightened sense of like symbolism and also connectedness and be like, oh, I was trying to reach out because something was going down. And I truly believe that was the case. And I and I think that most Latinx people are like for sure that it was definitely the case. You know, like there’s not even a question like my my I told my mom that I had texted him and she was like, oh, did you have a did you have like a sense like she just like straight up asked me. She was like, so did you have a feeling? And I was like, I don’t know. I think I was just asking if he’d been vaccinated, like, I can’t really remember what I was thinking at the time, but, you know, but it’s really interesting to me that, like, that’s a given in the way that you were talking about Galia and that’s a given that kind of lets us move through things in a way that I think embodies resilience. You know, that celebration really embodies resilience.

Dante: That’s a real thing, like my sister will sometimes text me like, hey, I had a bad dream and you were in it last night. Are you OK? It’s a real thing.

Galia: Real nice. I mean, my whole family says – so, we have a whole theory that the Backals know when they’re about to die, which sounds very bad. But it’s like this. This is common thing that has happened with every family member of my abuelo, when he passed, he usually goes on walks with my abuela and my uncle at that time. And he was like, go on the walk by yourself. And you’re like, why? Like, what’s going on? He was like, just trust me. Go on the walk by yourself. He lied down and he passed away. My other, my tío Mike, same thing. I went to visit him one last time. I was like, do you want me to visit you this weekend? He’s like, it’s not going to be necessary, don’t worry. And I was like, Why? I’ll still be in town. What’s the big deal? And the next day he passed and I was just like those weird things that, like, I really do believe that there’s something in the in the air in the attunement that, like we had with our ancestors, that we we feel it in our gut, in our soul. And it’s it’s a lovely thing. It’s just a very interesting maybe you’re right that every Latinx person who I’ve told these stories to, they’re like, yeah duh, like that’s something.

Noelle: And I think I think there’s something also like really fascinating about that interconnectedness in our storytelling. You know, I think that Latinx storytelling is a really rich tapestry woven of so many different cultures and traditions and like and and languages colliding. And I think that there’s an acknowledgment, I think, of meaning making that we do. And it’s like very much like. Yeah, that that’s like a meaning making moment. Like, let’s double down on that. That makes perfect sense.

Dante: You know, I, I’ve been, I’ve been reading from, for the students that I teach and for my own reading, I’ve been reading from Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz and in the chapter, and it’s like earlier in the book, it’s like the second or third chapter. He has a whole section, just about like colonization and like how, you know, what made it possible for the Spanish to colonize Latin America or what would become Latin America the way that they did. And he’s going through and describing all the horrible, horrible things that happened. And then and then he has this one sentence that just hits you like a bus. And what he says is that, you know, the majesty of mankind lies in its ability to translate the nightmare of reality into vision. And you can like that. And part of that is the ability to or rather like the goal of escaping the nightmare, even if just for a moment through creation. And I think that for our purposes, that creation like is that meaning making right. That like meaning creation part of it is a way of like translating all the, I think, chaos of Latin American history into something coherent, like into something that can be understood.

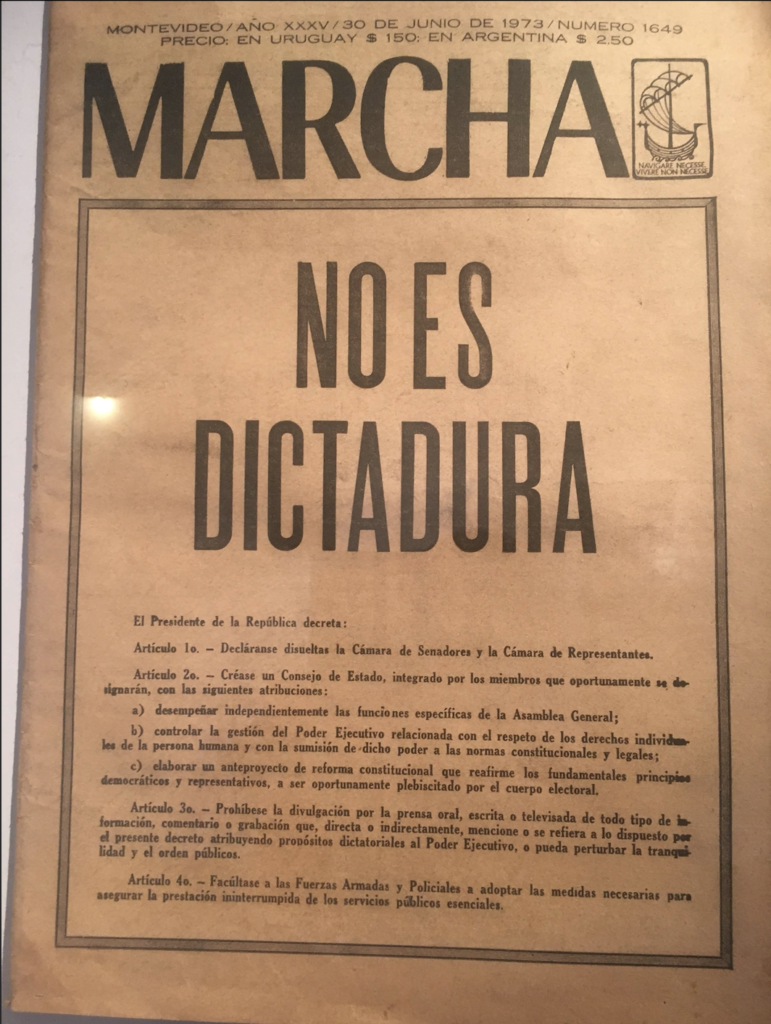

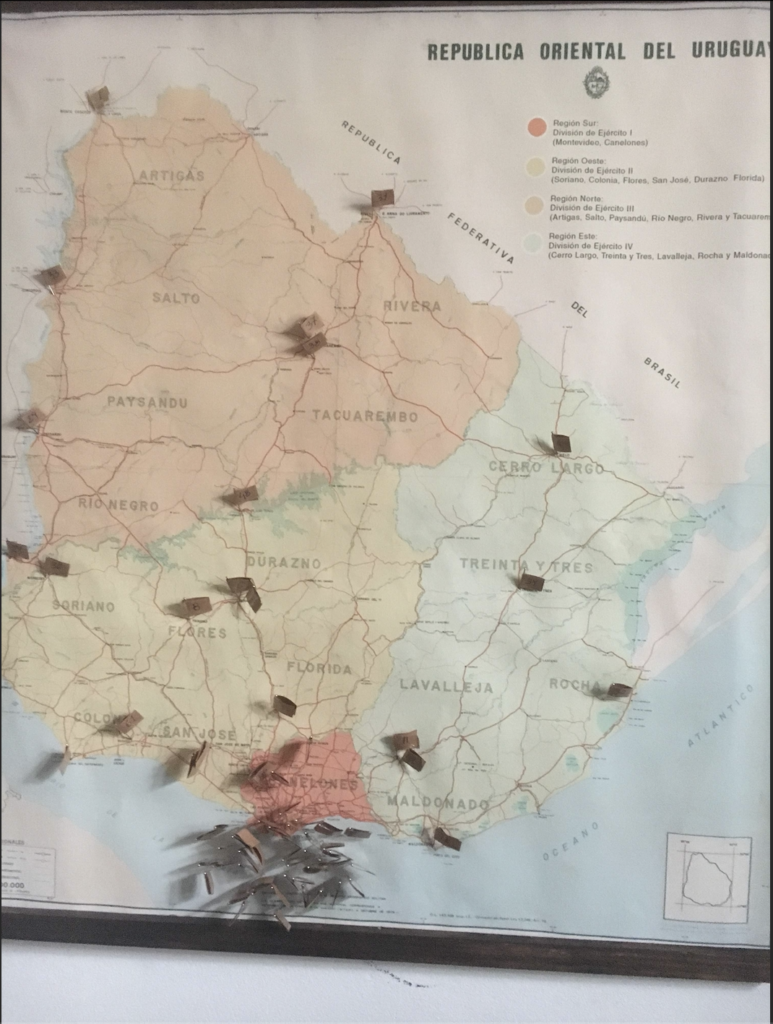

Noelle: Yeah, and I feel like that’s really reflected in this in the script and in our conversations around the script, like the dictatorship in Uruguay and also Operation Condor. So for those of you who don’t know the context, I will share Operation Condor is basically a US funded and backed initiative in six different like very specific member countries and then several other ancillary countries to kind of repress communism in Latin America in the 70s and 80s and sometimes late sixties, depending on what the timeline is. And so one of the things that keeps happening during this period is people try to do research – is number one it’s super recent history. So people don’t really it’s still it still hasn’t all been written down because the people that lived through it are still alive in most cases. And number two is that there’s been so much purposeful obfuscation that you’re kind of in the way that as a country or as a people or as a family, you try to process these things. It’s really confusing and messy in the way that grief is confusing and messy. And so I feel like now that we’re having this conversation, I’m really interested in what we’re talking about in terms of meaning making and like spirituality and magic as a way of meaning making because it feels directly connected to like trying. To do when Nieta is doing in the script, which is like try to make some meaning out of what doesn’t make any sense, like, you know, it’s like why did this happen? Why are people hunted and tortured for so long? Like, why did the whole world let this occur? Like and why did these countries like descend into this? And why was it all hidden from me that there are so many compounding and exponential questions that are live in the narrative that now that we’re having this conversation about grief and Latinidad? I feel like there’s a real, there’s a real sense of like, oh, like this is the way that you can make meaning of this time period and kind of sift through it to the best of your ability and still acknowledge its complexity.

Galia: It makes me think of a conversation we all had, I think over a month ago now. We were like, is this really magical realism? What kind of magic is this? And we couldn’t really name it. And now that we’re talking it through, like maybe that it’s what you’re saying, it’s not necessarily magical realism. It’s not this, you know, this theoretical theatrical device, but it is this coping, grief-y breathing mechanism of her understanding this within her own mind, in her own world that like maybe can be described as magic. But all of our quote unquote, magic is just directly related with ancestors and ghosts being involved.

Dante: I sometimes wonder. Sorry, Noelle, if you were about–

Noelle: No, I was just saying I agree.

Dante: End podcast. No, I sometimes wonder if you know and I know this is going to sound very like I’ve been awake for nine hours and it’s three a.m., but like I sometimes wonder if if like what in literature, if what in culture, whatever noun you want to put their. If what is referred to as magic is just kind of drawing connections, like drawing connections that aren’t immediately visible, I don’t I don’t know if that makes any sense. I might be talking out of my ass here.

Galia: No, no, no.

Dante: I think that. You know, I think that there’s there’s something kind of there’s something. Kind of documentary about this, not kind of there is something documentary about this piece. In in that like it is documenting one only, only lightly traumatized person’s journey to figure all this shit out. But in a way that kind of zooms both in and out. Right. It just kind of end like multiple times throughout the course of the play. It’s like this accordion effect that just happens throughout the course of throughout the course of the playwright in terms of what we’re actually looking at right now, we’re zoomed in on like Nieta by looking through her journals and then we zoom out through, like, the entire political scope of Uruguay at the time. And then we zoom back in to her and her father or her the memory of her father, like sharing amate. Right. And then we zoom back out and it’s, I think, in like like an Adam Curtis documentary or something, it’s like kind of telling this very personal, intimate story, but against this, like, broad sweep of history. And to me, I think that’s where I think the feeling of magic comes from. Right. Is like seeing all of it together at the same time. I don’t know if that makes any sense, but that’s that’s that’s what’s good.

Noelle: That that makes perfect sense. But is the three I’m feeling like, you know, like I think that that’s you know, when you watch all the TV, the procedurals or whatever, the TV shows where people have their corkboard and their little like pushpins and they have all the red lines connecting all the evidence and they like sit back and they’re like, wow. And like, I think that’s the feeling of like magic and storytelling. You’re like, wow, this shit’s connected. This is nuts. I do. I do think there is some magic in meaning-making. And in the reverse. It feels it feels crazy to kind of move in and out and kind of experience that that difference of scale. Because how because life, if you live linearly, doesn’t usually give you that experience of scaling in and out. It’s only in putting it into a narrative that that happens. Yeah.

Galia: Yeah, and it’s interesting because we’re scaling in and out on such a grand scale while also going back and forth through time. It’s just like this giant. I thought of, like, those old 90 balls that were like those contraptions that went in and out, that’s where my 3:00 a.m. mind went. But you know it makes me. It makes you think about one of what what the piece is named after El Cóndor Mágico, that specific story line being this almost trigger for Nieta within her memory, in her dreams, because if you don’t know this-I’m gonna try to say it without revealing the entire piece, but it is a fairy tale that Nieta was told by her abuelo about this magical bird that saved all of Uruguay and all of its people. And you will take that for what it is later. But it is such an interesting. It’s such an interesting thought, what you were saying Dante about going in and out and seeing it in different times and having that ability to step back and see the corkboard, because that specific story, that specific memory, you would not have the ability to see it for what it was if you didn’t have all the context, if you didn’t have the magic to put it into meeting.

Dante: Yeah. It’s this crazy thing where time and space feel dilated, right? Where time moves both incredibly quickly and incredibly like on this on this glacial march through itself. Right. And then it also is this is space feels dilated, too, because like, again, when we hyperfocus on Nieta and like, waiting at a bus stop or something, the world feels so small. Right. It feels so small. But then the story that her grandfather tells like makes the world feel so grand and large. Right. And the same thing happens when you look at, you know, when you look at the reality of Operation Condor. And then when you hyperfocus on this one, family, like the world, just kind of seems both incomprehensibly large and too full of questions to ever actually be filled out. But then you can draw these direct lines between different aspects like, you know, like Nieta keeps finding you just have to ask those specific questions about dates and times. Right. And those tiny little things will actually ground you in what feels like an incomprehensibly large, in-navigably large world.

Noelle: Yeah, and and the dilation also makes sense on some level, because if you think about if you think about the magnitude of the Cold War and its ripple effects throughout the entire the entire world, it’s just kind of overwhelming that like what’s going on between US and the USSR ends up affecting pretty much all these countries and huge and irrevocable ways that change their politics forever moving forward. And I think that that so you can’t kind of live with that without that context, like in interviewing relatives, which is something I’ve been doing for years now. And some of them are recorded and some of them are inspirations for scenes and some of them are totally invented interviews in the play. But it’s it feels like every time someone’s like, well, you’ve got to understand, first it was the US and what is now called Russia. And it’s like you can’t begin the story without the zoom out. And so I think I think it’s interesting that you’re calling it deletion because it’s like that maybe is what is happening in terms of action is dilation. But if you just hear the straight interview, it’s very much like, OK, let me give you the context, because you’re not going to get it unless I start breaking down the context about communism at large in the world at this time. Yeah.

Galia: And it’s interesting to explore that then today in the United States, you know, after after everything that has happened over the last few years, after what happened in January, specif, if even after the events of January I remeber Noell and I immediately started texting and being like this puts our piece is a whole new light now, because one of our beginning questions was how do we how does this piece relate to Latinx folks who grew up in the United States who may not know what Operation Condor is? What is that like generational trauma that this huge earth shattering event happens in January? We’re like, oh, it’s it’s this it’s this exact it’s history repeating itself. It’s, you know, the term communism and socialism and all these things coming back into our vocabulary and seeing it being used the way most of Latin America has already seen it being used.

Noelle: Yeah, because I think socialism is a big, scary ghost in the US and in terms of our politics, which also speaks to the play. Right. But but like it’s like a boogeyman, I guess is the word like you just you just say the name and then everyone freaks out and people can’t hear the rest of the sentence or the information. They’re just like socialism: bad! Don’t want it! Like it’s like the whole of their the whole of their experience. And it’s like a battle cry.

Dante: And it’s this thing we’re like, you know, it’s it’s this scare word a lot of people. Right. And it’s meaning has become like totally confused over the decades. But then, like, it’s also not that long ago that the Soviet Union collapsed, right. Like that was that was in nineteen ninety one. That was that was 30 years ago. There are people alive today who remember exactly like, oh yeah, I remember that day when the Berlin Wall fell or whatever. And it seems like in that time between like, you know, Soviet Union collapsing and now. Everything just seemed to like kind of flatten. Do you know what I mean? Just like. All right, well, I guess we’re just doing capitalism everywhere now. I guess that’s just what we’re doing. And like, suddenly it felt like politics just didn’t exist anymore. But like, no, they exist. The past 20 or so years have shown us they clearly still exist. And I think it does force us to reckon with all of these for lack of a better term ghosts that we thought were gone like ghosts of the Cold War, ghosts of Latin American history, ghosts of our own families like it. Events force us to do these events, force us to reckon with it.

Noelle: There’s this amazing commercial. There’s this amazing commercial that I just remembered. I think it was during either the 2010 or the 2014 copa mundial, I don’t remember. But it was like a marketing strategy from the Uruguayan side about an upcoming game against Brazil. And basically the commercial goes like this. I’ll explain to the commercial and then I’ll give context. It’s basically this this guy in a white sheet just running around and showing up in random places in Brazil and scaring the shit out of whoever is there, like over and over again. And that is the whole commercial. That’s the entire ad. And then at the end, they they put something up about 1950, which is this famous World Cup match between Brazil and the way in which Brazil basically lost the game in this huge and shocking way. I can’t remember if it was like a self goal or something really upsetting, but it was very it was very much expected that Brazil was going to win and it was on Brazil’s home turf. And it was like so it’s like this ghost of this loss. And like Uruguay was just kind of bringing it up in this ad to kind of taunt Brazil, which is a border country. And I just every time I think about kind of the ghosts of socialism or like the ghosts of our past, I also think about that weird commercial and like how how two opposing sides of, you know, an athletic match are bringing up the ghosts in order to get each other kind of riled up. And that’s exactly what we do in our politics. You know, like you’re like that’s that’s often what the right is doing. They’re going socialism. And then the guy and the chief shows up and everyone starts screaming. And then it’s completely it’s complete madness. It doesn’t make any more sense. You know.

Galia: My new favorite metaphor.

Dante: You know, football is also this enormously political sport, right? Like like an entire country’s hopes get bound up in a football match. Right. Like, you know, Diego Maradona passed away recently and, you know, the world famous football player. Right. And there’s that clip of it’s called like the goal of the century or something where like Maradona, like he scores this goal. And it was it was Argentina playing against the United Kingdom or playing against England. Right. And this is at like the height of the Falklands War. Right. So or like it was either at the height or right after the Falklands War. Right. So there was there was kind of like bitterness between the two countries. And Maradona makes the school from across the like across the entire stadium, like he makes what he just runs the ball all the way over, threads the needle like three times, and then like between English players who are coming at him and then, like at this crazy angle, he scores the goal. And like the you know, the announcer, I can’t remember his name. Like, he’s a famous announcer, though. Like he says, like, you know, it’s like: Thank you, God, for football. Thank you, God for Maradona. Thank you. And like you can see, like, oh, there’s real pain that was just kind of let out all at the same time, like because of this one goal. Right. And you’re seeing it now, too, with just like football fans realizing that, like, these football clubs are being bought up by, like private equity firms and stuff like that. It’s like it is this contested ground of like serious politics between like the people and like, you know, the owners of the stadiums and stuff like that. So, yeah, no, that makes total sense, though. I’d love to see that ad,

Noelle: So I’ll send it around. I, I don’t think it was a self-goal actually. I think it was just an upsetting goal. I was thinking back to my memory after I spoke. I was like, I think it was just really close to the end. The game seemed like it was over and then it went the other way. Were you going to say something, Galia? I can’t remember.

Galia: No, I was I was thinking about one of you said it of. Now, the ghosts of history are coming up, right? And like how we use socialism as a scary ghost – now I’m thinking of always this man in the sheet, and it makes me think of-the thing that really shocked me when we first started getting into this piece because I didn’t know anything about Operation Condor. No idea. And when I looked it up last year, the trial was going on in Italy of many of these dictators that were involved. And like the United States had, there was nothing in the news about it. We had no idea. And, you know, you dig deeper into all this research. You see how involved the United States was, how parallel journeys it is to what’s happening right now, like when everything went down January. This is, of course, after we did all this research on Operation Condor and everyone was like, how did this insurrection happen? Like, how did how do these things get out of control? And I was like, well, we kind of showed other countries how to do it. But this country does a really great job at hiding the history that they don’t want people to know.

Noelle: Yeah, and I think it’s also really interesting because recently I started as part of my very strange research, I started reading-I think it was a deposition because it was very boring to begin with, but then it got more interesting of the ambassador to Uruguay during the dictatorship, just like him talking through his entire career. It was like 40 pages long. So I had to scroll to the part that was really relevant. But it was really interesting because he kept bringing up like, well, it’s so ridiculous because people always asked me if I was like an agent for the CIA and like not everything’s about the CIA in Uruguay during this time. And it was like really fascinating because I feel like. I mean, maybe not like maybe the ambassador had nothing to do with the CIA, that’s that’s possibly true and maybe that was a safer way to do things. But I also find it really interesting to just claim that nothing was happening at all is like a very strong and strong and wrong, very strong American stance to go in that direction and to just be like, no, there’s no way. How could anyone think that? Like, well, there’s lots of circumstantial evidence that might make people think that, you know. So it’s really interesting, like big refusal of what you’re saying, Galia, which is just like we don’t in this country, in the US, allow people to to know what’s an inconvenient narrative, because we’re very much hyped up on kind of the myth of ourselves. And that is partially why I think. We’ve talked so much about this myth about the Condor that begins the story and does activate Nieta because it’s like it feels connected to the mythos of nation building that we are we sit really close to in this country.

Galia: And for reference for listeners who don’t know about the US’s involvement, it runs pretty deep. It’s to the point that they opened up a training camp in Latin America to train Latin American armies on torture, on proper torture methods and how they got information out of people. So although America didn’t pull the trigger or do the interrogations, they gave them the methods, they handed them the tools to do so. And there’s also a lot. From our research, a lot of evidence that suggests that the government at that time, very high up in the government – our least favorite Kissinger was directly involved with many assassinations and many placements of power within Latin America. And that has been I think most of that has been proven now by the FBI at this point. I turn to Dante for all this information out because he’s our resident genius.

Dante: There’s a there’s a great book on all of this. I mean, I say great in the sense that it is an enlightening read. I don’t mean great in that you’ll have a you’ll have a hoot of a time. Killing. Hope by William Blum is is a book that goes into the United States involvement in the toppling of governments around the world since the end of the Second World War. And there’s one chapter in there about Uruguay where, you know, William Blum breaks down U.S. involvement in training death squads and like training like that, Uruguayan military and methods of torture and stuff specifically through this one dude Dan Mitrione. And so, yeah, he William Blum gets into it. And William Blum is the sad thing is that that book, like you could stop a door with that book and it is still not a comprehensive look at like it’s by no means comprehensive or exhaustive as an examination of our involvement in in like world politics and behind the scenes.

Noelle: Yeah, and what’s interesting about the Dan Mitrione stuff is like that that’s actually controversial, which I think is also really funny to me personally. You know, it’s like if you if you’re speaking to people in Uruguay or even speaking to people here, like it is a hot topic for various reasons. Like, obviously, the US doesn’t want to be affiliated with teaching torture techniques and having kind of enabled and encouraged these atrocities to happen, but on the other hand, from the Uruguay perspective, like you really don’t want to give up your own sovereignty, your sense of it. So it’s like it’s an unpopular narrative. And in in both ways, no matter which way you cut it, and it’s much easier to be like it was very complicated. And that’s like the end of the story. You know, that’s like you don’t get any more details. Very complicated. Very complicated.

Dante: Yeah, yeah. It’s like, well, look, a lot of things happened, all right? And it’s like I don’t want to. Yeah, but somebody did them. Somebody did the things..

Noelle: Yeah. Yeah. Becauseit’s like a slippery slope for some of these people to vote for reconciliation. Like there they are really certain that they’ll be chased after because they’re there are things that they could be chased after. So it’s easier just to say nothing.

Dante: Yeah.

Galia: And I mean, we just had a controversial narrative is you could see it within the piece, right? You could we I think Noelle what you do an amazing job that is showing how the everyday people of Uruguay, people who lived there are people who don’t got so many different sides of the story. Right. And that’s like that’s even looking back to what we’re talking about, how socialism is used in the United States. It’s it’s used in a positive and negative way by Latinx people because of the narrative they received in their country of origin. Right. Like when I was doing research on why certain people voted a certain way in 2016, a lot of the research showed that it was a lot of Cubans who came from Cuba and had this experience with socialism. And they were like, why would I vote for someone who leans socialist? Because then we’re going to fall into a dictatorship. And I think that’s a conversation we see in the play several times with several different characters who blame the socialist for the dictatorship while also blaming the dictatorship for the dictatorship.

Noelle: Yeah, it’s it’s an interesting like because all of that is also true, right? Like I whether you’re speaking to someone from Cuba or you’re speaking to someone whose parents escaped the Soviet Union like it’s not false that like those people who experience those things and those regimes did lead to dangerous and oppressive regimes. So it’s also what what the part that gets trickier is the application of the label of this is the same is that it’s the false equivalency and also the distortion, of course, of of who’s being painted as socialist and whether they are, in fact a socialist or just want some regulated capitalism. But I, I should hang my hat on that, you know

Dante: It opens up this debate like what’s the what’s the proper way to politically advocate for anything. Right. Like what is the proper way to politically advocate for left policy? Because and you see this debate happening today like, oh well, is it appropriate to riot, is it appropriate to loot and like framing it I think morally misses I think leaves out a lot of the political reality I like. And that and that comes down to like that’s just as true in these justice for George Floyd protests that we saw last year as it is in this debate of like, well, what was the proper way for, like, you know, Uruguayan leftists to advocate for, like, socialist policies? Right. Like, would it have been good? Would it have been preferable or safer or more just or more moral to advocate for for it through elections? Again, framing it morally is maybe not the right question to ask, because like Chile was a member country of Operation Condor. Right. And the the democratically elected Marxist president of Chile, Salvador Allende, was violently toppled. His government was violently toppled by the incoming Pinochet regime. Right. And we’ll take it back to our old buddy Kissinger. The problem, according to Kissinger, wasn’t that the Allende government was violently suppressing political dissenters. The problem was that the Allende government wasn’t doing that. And like suddenly you have this example of a mass of working people on Election Day choosing Marxism. Right. Like choosing socialism. And that couldn’t be tolerated either. So it it it I think you know what I think, Noelle, this play does in a really interesting way is like raise that question of like, what is the actual politically political reality on the ground, though, how long would peace have actually lasted, though, like if it had been done peacefully?

Galia: That makes me think of specifically that monologue within the piece talking about the Tupamaros and their role in everything. Right. Like we have this mom character at one point describing them as the reason for everything going down the way it was and that they were too extreme. But in another retelling, throwing it back to how we tell stories differently every time and another retelling kind of throws it in as a side flurry of action that happened. And I think that those are very real perspectives of what those groups did.

Noelle: Yeah, yeah, there’s and there’s a constant shifting of blame for the people that initiate violence in opposition to what they see as violent oppression, you know, it’s like it’s it’s the problem with respectability politics and it’s often the conversations that you were talking about, Dante, is like kind of this sense of like, oh, man, like now now we can’t even have a conversation because we’re table six talking about what a civil way to do something is when something repressive and violent is happening, which is kind of absurd. It’s like and it’s very much grounded in the sense of like giving your power away as far as the people who actually give government power. So I think that that’s also a really rich conversation that lives in the piece is kind of is kind of this conversation of like how how does democracy work? Do you know? Like and who who are the people that give democracy its power? And is it actually the people and what they want and what they’re asking for and the various and large spectrum of ways that they ask for things? Or or is it actually the US kind of anointing like you are acceptable to democracy? You are not an acceptable democracy, which is which is very much what we experience throughout the piece, is kind of those diverging perspectives of both seem to be true or trying to be true. And it’s very confusing. And we try to traipse through that confusion and that complexity with our protagonist.

Dante: Well, and that’s that’s a really you know, that’s a really Cold War idea, right? Like this idea of there being these two distinct political poles. Right. On the one hand, you have the US and capitalism and markets and then on the other hand, you have the USSR. Right. And socialism and all that stuff. And I think that like. At least on the US side, I think. You know, we really did subscribe to that that that latter version that you posed, Noelle, we’re like the the the the biggest liberal capitalist state can anoint democracy onto, you know, all the others like can annoint the status of democracy or not democracy onto all the others. Right. And that, I think, is a kind of arrogant position to take specifically because like, OK, well, why why does this one country get to decide which which ones are democracies and which aren’t?

Noelle: Because colonialism.

Dante: Right, exactly. Colonialism and feudalism turning into capitalism and then over time, wealth just accumulating wealth and therefore political power just accumulating over generations.

Noelle: Yeah, I mean, it’s it’s very much neo colonialism and it feels like an all to me a very clear line of the experience of like the IMF or other other governing bodies kind of messing with people’s currencies and deciding, you know, and I could I could nerd out about this all day. But but there is kind of like this sense of like you are doing this the way we want and therefore we will give you what you need, which is also directly in opposition to how we use sanctions in the US and how I believe this is an opinion, this is not fact listeners, but I believe very much that, like, sanctions are ineffective and and are basically a way to kind of coerce people. And I don’t think that they should be used at all because they are a colonial tool, a neocolonial tool. But there’s a lot of people that don’t believe that. So I think that that’s a really complicated conversation. And what are the tools we use and the tools in the play a lot more are usually a lot more direct because like you mentioned, like they are literal training-torture training techniques. But I think it’s all kind of on this very clear line that to me is very much how neocolonialism just continues to perpetuate itself and these patterns continue to perpetuate themselves.

Dante: Yeah, and I mentioned this before we started recording, but for listeners who want a book that gets into this, Open Veins of Latin America by Eduardo Galiano, it’s a great book to read. Like, I think that is a must read for anyone who wants to, like, kind of familiarize themselves with this stuff. It’s the subtitle of that book is Five Hundred or Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. And what Galiano does in that book is draw those direct lines between, you know, like colonialism, like we saw in the fourteen hundreds and fifteen hundreds. And he draws the direct line of those kinds of relationships to these kind of like IMF style, dictatorial style relationships that we see today. That’s a great book for exactly what Noel was just talking about.

Noelle: Also, Uruguayan.

Galia: I hear, because it feels like in this country and we talk about the US and Latin American relations, we talk about it as if we’re talking about like when the European settlers first got here. Right. Like I feel like I hear it in context of, oh, yeah, you guys were in Texas and California and then like, we bought it, things happened. And we don’t talk about how like how those veins and those lines are still so interwoven, so interconnected. Even putting aside the the issue with immigration policy, this country with the border. Right. But the the cultural implications of this came up many times in a very strange way. But in a lot of our interviews, we kept hearing Disneyland. We kept hearing that Disneyland was like the thing that Latin Americans were told were like-that was if you made it to Disneyland, you were wealthy, you had made it in this world and like you were basically American, whereas like Disneyland is a tourist attraction, that’s like sure fun sometimes, but like it’s not this like cultural holy grail that exists throughout all of Latin America.

Noelle: But it is to some Americans or I guess United Statesians. I’m trying to move away using…[Americans]. Well, because it’s very it’s very confusing. In Uruguay if you say Americans, they’re like – “you mean us?” Like like “We’re also South Americans. So I don’t know what you’re saying.” So I’m trying to move into the United States. But but I I’ve met I don’t know. I’ve I’ve had coworkers and stuff who are like it is their Holy Grail and they are United Statesian. And they’re like, I go to Disneyland like every month or every two months because I just love it. There’s so much. And I’m like, I mean, that’s that’s fine. That’s great. I’m glad you have this thing that you love. But I also really like wrapped up in money in a way that I don’t I don’t I just don’t have any. I don’t I don’t have any hobbies like that, like I can’t I have no hobbies that I have poured tons of money into that I just, you know, just kind of go and experience and be like, this is what it is to be happy here. I don’t think I don’t think I ever experienced that. So it’s really fascinating to me. Like what that means, what you’re talking about Galia.

Dante: But it’s wrapped up in money both ways, both for the visitor to Disneyland or Disney World and the town immediately surrounding it. Right. And the proof of this this this like this drove this image drove me insane when I read it. So the state of Florida, I think, just passed this like, quote unquote, anti-rioting law that just makes protesting illegal or makes a lot of forms of protest just illegal. And when they were giving a press conference about it and when the sheriff of this county was saying, like, this is why we’re trying to keep this state safe for visitors and stuff like that. And he holds up a picture of Mickey Mouse on a beach. And, yeah, I don’t like maybe this isn’t real and the Internet is just like poisoned my mind. I don’t know. I don’t want it to be for real because it’s like too apt a metaphor. Like if you made this as a political cartoon, you’d be called a hack. But it like it is this really true expression of what you know, like Disney World and Disneyland and what that stuff means to like kind of reactionary state governments and like reactionary business interests immediately surrounding them.

Noelle: Yeah, they’re exporting narrative. That’s all I have to say.

Galia: But it’s like Mickey Mouse is almost saintly and magical, like to the point that when I was doing a show recently, they wanted this, they wanted to represent this Mexican who was like really wanted to be American. And I was like, put them in a vintage Mickey Mouse shirt, like, I wish I was kidding. But like, this is like that is the level that that symbol has meant to so many people. Like, it does mean success in a lot of ways. And, you know, it makes me question, as I say it out loud. The. And this links back so many thoughts about what we’re talking about, people born in the United States who are Latinx, not knowing about this generational trauma, but also the inherent need to feel United Statesian, or American right to be accepted as American. And what that means to a lot of Latinx folks. And I feel like it’s a conversation that we started to talk about and I think is even a conversation that’s weaved into the piece of Nieta’s inner battle of what it means to be a United States citizen versus a Latinx or Uruguayan. And that question, I don’t know where I’m going with that, but it’s just a thought that’s bubbling in my brain.

Noelle: But I think it’s really relevant because I think it’s part of the reason that. The inquiry can even begin, do you know, because it’s it’s hard, it’s it’s easier to kind of be like, well, what’s up with this story that I’m hearing from both sides? When you’re sitting at an intersection, then when you’re like living on one. And I’m not I’m not I’m not saying that, like, my relatives in Uruguay or people here don’t do this research. They do. It’s just there’s an inherent tension that you feel kind of forced to explore when you were holding all those identities because they kind of pushed up against each other. So you’re already, like, asking the questions like, wait, what, you know? And I think that’s kind of an important thing for the character because she she sits there at that intersection is kind of always wondering to herself, like, what does this mean? Like, should I which side of the should I feel? Should I feel angry about the sovereignty question and the fact that in Uruguay sovereignty was in some ways denied or in some ways like interrupted by the US or should I feel guilt, you know, because I am United Statesian or what have – That’s that’s a really compounding and weird question, which I think a lot of folks are encountering. Like, it’s it’s not easy to actually be like, well, the country that I was born in and then immigrated from as a young child or the country that my parents was born in, I’m going to claim that high ground, even though I don’t live there and it doesn’t make sense, like you also feel like kind of very much trapped in US narratives. So that’s also really interesting to me, too, is what you’re bringing up is that that tension of holding both.

Dante: I feel like I think I’ve mentioned this in previous conversations that we had, I feel like. I think I just have I think I just have the United Statesian of that, like, kind of inner conflict because, you know, my family’s been in Texas forever, right? Like, I I’m I’m not Mexican. Like, I’m not from Mexico. I’m I’m from Texas when when I get that annoying. But where are you from, question? Like, my answer is always I’m from Texas. That’s where I’m from. And as and like you read Texas history, it’s wild and like insanely right wing to like read. And but then it’s-but I don’t know the term for, like white Texans, like was Texian, right, as like a sociological term, I don’t identify with like Teixans. I like if I had to use a word, it would be Tejano. Like that’s actually describe myself as like to the degree that like I feel like I don’t really feel any allegiance to one place or another. I just don’t. But if I had to say like. And again, it’s not even allegiance, just like how would I describe myself, I guess Tejano. So it’s like it’s it’s I think it’s interesting reading like the history of Latin America, like specifically like Central and South America from the perspective of someone who is not like from like geographically or politically. Latin America. Right or not what is typically considered Latin, like I’m from Dallas. So it’s I think it’s a slightly different species of that intercoms life that I have. But it’s one that that this piece really gets me to start thinking about, like as someone who lives here and is from here and yeah.

Galia: Yeah, it’s always so interesting to have this particular conversation with other Latinx folks because it is such a wide variety of perspectives, I think this country always very easily wants to put us in a box of like you’re either born here or your parents or your parents immigrated from here or you immigrated from here. Those are like your only options. And that’s that’s not the reality or the reality of identity. I think there’s what you’re saying, Dante, like not feeling like you’re Texican, not feeling all these things, like it’s just so real. I, I really feel that. I feel that story from you and for me, like I think. For me, being first gen, I didn’t realize it was so weird, I didn’t realize I was different until I went to college and like had pasta for the first time or like told people I ate lengua, which is tongue – it’s delicious you all, all the time. And like, it wasn’t until I was away from home, away from being in like Los Angeles, where you’re surrounded by Mexicans and nothing’s really out of the blue that I realize that my experience was different. And then even hearing being in a college and hearing other folks have parents who knew how the college system in America worked, who, like, you know, didn’t have to do those those other steps for their family. I think there is a an interesting storyline with not just Latinx folks I think all other folks and underrepresented groups in this country of having to battle with your identity, of being the United States American and the other cultural parts of yourself.

Noelle: And I think that’s because we have a real obsession with purity in the US, like I don’t think in other countries that says I mean, maybe this is silly, maybe I’m wrong. I don’t have enough perspective to know. But I just don’t feel that people are this obsessed with what a pure American is like there’s just a real sense of, like purity culture in terms of like and I don’t mean like Christianity, but that’s a different kettle of fish. But but I mean, like literally like the conversations we have about who we are descended from in this country and whether they are Mayflower adjacent or not is like so crazy. Like I like I think it’s so nuts. While I also like and excited to explore my own ancestry and I’m so pumped to like, hear stories that have been passed down from the eighteen hundreds, it’s also like really strange to be like where are you on the spectrum. And I think that that’s I think part of the reason that I think people from cultures that aren’t European and flattened out by immigration over the years, experiences like grappling with identities because the white supremacy is very real. It was like a real like tracking to how what what is your relationship with white supremacy and whiteness and the sort of purity context, you know? So I don’t know I don’t know where I was going with that, but I do feel like that lives very much inside of the play in terms of questions of loyalty and in terms of questions of like affiliation and in like country like country anger and like country connection. Like it lives very much in that tension, too, of like that that strange white supremacy that is very us made.

Galia: Yeah. Because I think although this piece centers around a a Latinx family a Latinx story line and this Latinx history, there is something that’s-that spans identities and spans cultures in what you’re saying in this idea of like finding your identity, dealing with generational trauma, dealing with the history and the stories that came before us. I think it’s something that everyone can relate to and it’s something we’re all exploring more now that, you know, social media and the Internet. And we’re being, I think, asked to explore that more in our daily lives.

Dante: This also reminds me of something that. I talk to my students about when in the first unit of plays that I give them, it’s just like these are plays that kind of get at ideas about colonialism and get ideas about like colonization and all that stuff. And one of the things I have to explain is like there’s no one way of being a Latin person. There’s absolutely no one way, just like there’s no one way of being from any other marginalized group. Right. But, you know, with Latin America in particular, like race and race relations are so much more complicated in in Latin America than they are in the rest of like in the United States. Right. And it’s like, you know, systemic racism expresses itself in different ways. Like and the terms that we use here are not at all the same terms that we would use if we were in a Latin American country. Right. Like, you know, someone might find the phrase person of color deeply offensive in another part of North or South America. And that’s just going to vary depending on that specific place. So one of the things I try to get through to my students is that, like, it’s kind of to like unplug themselves from this, I think kind of really reductive idea of what like, you know, white supremacy actually is just just because the example that we see in the United States, like, is real. It exists. But it’s not the only way that this problem exists. And in order to kind of get at these players and really dive into the meat of them, we have to understand how it works in other places as well.

Galia: And I understand that it’s I love that you’re telling your students that because it’s also a conversation that is just now actually happening in Latin countries like I think we have been so late to the game of naming that and naming the the class race structure that is inherent in our culture. And it’s you know, I wish I wish I had someone in high school to tell me like not all Latinx people are the same.

Noelle: Yeah, for sure, my parents didn’t tell me that, like, just my lived experience was always very, very much like, oh, this is a thing that Latin people do. So we do it. And it’s like, is it is it a thing that all Latin people do? Because I know some of the venues across the street don’t do that, you know, so like just like running up against, like, evidence of other Latin folks doing different stuff and just being like, I don’t understand where these generalizations are coming from. And the answer is usually a lack of a complex and nuanced conversation about race and culture, you know.

Galia: Yeah, I mean, reflecting just on that, I recently went back to Mexico with my fiancee and he was his first time going to like actual Mexico City, and he was kind of shocked of the class race, clear structure that was just around you at all times in Mexico and the way I mean, like I’m being a white Latina, the way that I was seen in the city, the way that, like, it’s it’s segregated without I mean, they don’t Mexico doesn’t know the term segregation, but that is what they do. And he was so shocked by it. And I think it’s it’s so interesting seeing that different perspective. And it, again, reminds me Nieta’s journey of like thinking back on your memories, because it had me then think back on my time as a child in Mexico of like who we grew up with, of what how I was viewed at all times. And I think with us having a similar journey with the Cóndor Mágico story of like, oh, wait, let me think back on that moment. Let me think back on my experience in Montevideo with my dad. How was that actually different than how I see it now?

Noelle: Yeah, that recontextualize, the constant contextualization, I feel like it’s very much like it’s very much in the zeitgeist it’s now because of the more the more nuanced conversations we’re having about race and class and colonialism, I think. But it’s also just something that happens as you get older and you gain more knowledge. So there is something. I think sort of timeless about like, OK, I’m an adult now, I can understand these more complex topics about a dictatorship and torture and and what it means to live under curfew and have be graded at school based on your loyalty and and rethink about all the stories that my father told me when he was young, you know, like, OK, what did that story actually mean? Because, like and what did it mean when I when I was told that he would skip school like my sense when I was younger, was that he was skipping school because he was a miscreant, kind of like the sense of malcriado, that sort of thing. Right. But in retrospect, it’s like he was going to basically a school run by military men who weren’t educators. I wouldn’t want to be there either. Like, you know, like it’s just like that doesn’t sound fun. Like and getting in conflicts with people who are generals or generals wives that teach you like, why go? You know, so I think it’s really interesting as you as you gain knowledge and you recontextualize and I think that is maybe part of the dilation and and the magic that Dante was speaking of in the beginning of that constant recontextualization.

Dante: Because like you don’t, you know, I. Sure, there are like there are facts of the case that you keep coming back to, but you don’t see those facts as they are, you see those facts as you are. That’s the difference here, right. So every new situation that you find yourself in or every new phase of life that you find yourself in, just by through no effort of your own recontextualizes everything that you thought previously was the case.

Galia: It’s experimenting also with, you know, what you see as a child versus now what we’re all saying, I think that. That playing with time and playing with where we are mentally and emotionally, I think it’s something that plays into that extremely – right? Because you not only are older and see things differently, but your emotional context and what you’ve gone through is going to color all those situations differently as we see over the course of the play. I think the Nieta that we end up with, even if we plopped her into earlier scenes, would handle those scenes and see those scenes completely differently just because of everything she’s learned and gone through since that moment.

Noelle: Which I think is also really beautiful in a way that it’s a performance text now — so it’s meant to be repeated every night, or multiple nights, or multiple performances. So there is something sort of beautiful — thinking about when the play does live on stage of an actor and actors embodying this sort of journey of learning and knowing and growing and then recontextualize every evening through the ritual of performance, what those scenes mean. And so and one of the things I greatly miss and that we’re kind of doing virtual theater or not theater at all is kind of this sense of that virtualization of like, OK, we’re doing another performance of this and we’re doing it with more information and recontextualize. And we’re not because it’s like we’re not going to necessarily make the same choices with the contextualization that we have. And so I one of the things I really longed for and hope for this display because I love it, it’s my baby, but also because I’m having such a good time collaborating with you is that we at some point get a chance to see that through a run and kind of see that recontextualized. And that happens in the performers bodies. And as it’s manifested on stage, I think it’d be really rich and fascinating to see how it changes.

Galia: Yeah, I love that you brought ritual into the space, because I think that is such a big theme of the piece (and of just your writing in general, Noelle) is ritual. And these not just ritual in storytelling, but ritual in everyday life. And I agree it-my mind just like race to several places of like how would this actor embody this every single night? What are the rituals that would that would be altered just because of lived experience?

Dante: But even like I’ll speak to this a little bit as a dramaturg, this is like my nine billionth time reading it. I read it again last night in preparation for this for this conversation. And, yeah, it’s but I see it in my head differently each time I read it. Right. Like the text is the same, at least on a single draft. The text is the same. [Noelle starts laughing.] But just and that’s I realized that is not a dig at you, Noelle.

Noelle: No, no. I’m just I’m just laughing because it’s like I’m always changing the text on you guys. Go on, Dante.

Dante: But yeah, like if if I read through like one draft multiple, multiple times, I still see it in my head differently each time. Like there are some things that I keep coming back to. There are like particular theaters that I’ve been in or that I’ve performed in, that I see this play in like individual pieces change. Right? Like I still like, oh, well, this character walks out that way instead of that way this time or like, oh no, this is on stage behind him instead of that thing. And like it’s I think. Right, just the ritual of reading the thing rings out because like, inevitably all those differences in what I see in my head, in the theater of my mind, I guess, are influenced by like other things I’ve read, other things I’ve seen out in the world of movies I’ve watched, other plays I’ve gone to Zoom readings or something these days. And and as a result, like I come back to this text with fresh with a fresh look on it, just because of all the new stuff that I’ve seen since then.

Galia: Yeah, 1000 percent, it’s one of my favorite moments when we all do these meeting and we do a reread and Dante and I will be like ‘Wait but this line this time really stuck me in this way.’ And it’s been the same line. We’ve read the line 20 times, but for some reason, every time it’s a new it’s a new line. It’s a new meaning. And I think I mean, that’s I’ll be cheesy and I’ll say that’s the magic of live theater. But I’ll also say that I think it’s your writing Noelle in that to me that’s so intentional and it’s intentional because you also, in our minds, I think, already set up an unconscious understanding that we will be doing. There will be ritual in this play. There will be repetition. But just like Nieta, which I love, is the audience is experiencing what Nieta is experiencing we are hearing the same story, being told different ways every time. So of course we also take in the same lines, different ways every time.

Noelle: Yeah, because I do think there’s something really interesting about repetition, obviously, like the script has a lot of moments where the same story gets recontextualized or interviews where something comes back or a loop that you see at the top and at the end, like there’s just a lot of moments where that repetition is embodied. And I also think it’s really fascinating to hear. I don’t know, I hear that we’ve all kind of been in this kind of like nine month period, sort of working on this-we’re not nine months yet. But, you know, like in this gestation period when we can’t work with actors and we can’t really be in space together, like, I really wonder what kind of like this focused kind of text work and like wondering aloud how that process is different than the other ways that we make and what that will mean for when the piece actually gets made. It feels like it shoots it out of a different kind of canon, if you know what I’m saying.

Galia: A thousand percent, because I think what’s been lovely about focusing on the text so much, and we realize this even more so when we brought in a designer to a conversation last week, was that because we’ve been talking about the text so much? Because we I feel like the text is engraved in all of us. We have created design elements or seen certain parts of the piece that, of course, as directors, as playwrights, as dramaturgs. We always have roles of the play. We’re always worldbuilding. But I think when you’re reexamining specific texts so many times you find that there are design elements or pieces that need to exist in order to support the text versus I feel like in other in traditional theatrical productions you find the design elements after the text has been built, you know what I mean?

Noelle: Yeah, yeah, and I think that’s part of what is great about the intentionality. That you kind of decide to approach the finding serious with-is like what is what is best for the development of the script further? I mean, I can probably keep reiterating on drafts. I’m a writer. I’ll always rewrite hopefully until the production, until its opening night. And then I’ll be like, I can’t do it anymore. Not allowed – people to get mad. But I-But there but what is what is in terms of development is this gift of like you know what we don’t have and we were not able to do is kind of have these conversations with designers also as dramaturgs in a different way. And that feels like a real gift that we’re kind of giving ourselves because we could just keep reanalyzing the text and keep put back and keep putting acting intentions on what is ultimately really a physical piece that really needs to be embodied. Or we could go in another direction and start kind of trying to build the visual and physical world to the best of our ability remotely. And I think that’s a really exciting thing to think about for the finding series, is what what that will manifest as. Yeah. I also wanted to connect a little bit back to what we were talking about at the top in terms of like grief and change, to kind of acknowledge the the strangeness of having lost my abuelo, like right before right in the middle of this process. And I’m like very curious. And one of the questions I wanted to just pose to Dante and Galia it’s just kind of this sense of like. What what about the text may shift in terms of talking in terms of the darkness of the piece, like I don’t think the piece will lose its darkness because it’s impossible to talk about dictatorship and be like light and fluffy. But I do wonder, like now that we’ve talked kind of around, like Latinidad and grief as a celebration and la vida es un carnaval and I can keep going. But, you know, it’s just like what? What what exactly are the are the threads that may get memorialized is a big question, because I do think there’s a bit of a shift that is happening and I say this without knowing.

Galia: I think of the door, and this may not make sense to a lot of our our listeners, but there is the symbol of this magic door that has to that connects so much to ghosts in our story. Right. And now with this idea, talking about Latinidad talk about them always being here with us and how it’s telling their story to honor who they are, I think back on this door and how we weren’t sure originally where it led or what what it did. And now I feel very passionately that this door is that that ancestral plane that is always there, like the door is always there. Our ancestors can always walk through the door and they can always give us the stories. It’s just they have to open it or we have to choose to let them in. And that to me is hopeful. And it’s like a it is a lovely little light to the idea of why these ghosts appear in our story.

Dante: I think also-and I agree with what Galia saying I want to add the kind of like and here’s the gut punch of that, I think also because-yeah-there is the hope there, I think also that comes with a great deal of responsibility too, right? Like because it is a choice that you make, I have to go through that door to let those ghosts, to let that stuff in. It comes with a great deal of responsibility. And in my view, specifically, to be honest about what’s on the other side of that door. Right. You open it, you walk through, you look, you catalog everything that’s on every shelf and whatever next room is in there. And you be honest about what’s on, like, every single shelf. Right. Like for for good or for bad, if we want to use those terms. I know I said earlier it might not be useful to frame things morally, but I hope you I hope you take it in the spirit that I say that. I think I think the chief responsibility that comes with that is being honest about what’s on the other side.

Noelle: Yeah, and that does feel like a big theme of. Kind of the way the people celebrate people passing and talking about those who are here but not here is kind of this sense of like a good, a good funeral. It’s not one in which everybody’s like “he was a great guy. No flaws, good times, always basically a saint,” no. Like a good funeral is like one where you actually, the people that go really knew him and are like “great guy, really told some horrible dirty jokes though” or like or, you know, like just like we’re able to make really big, like, jokes about weird things this person would do or fucked up things that they would do. And I think that’s really actually really important is to in order to grieve and celebrate a whole person, you have to do what you’re saying, done to it and celebrate their wholeness honestly, because otherwise you’re kind of creating a flattened version of them instead.

Galia: And it makes you wonder for, you Noelle, because originally we had been talking about how abuelo is the passage to papa in the piece right there where this is not just for Nieta to find out about abuelo, it’s really about papa. Now, I wonder if that’s going to change for you in the sense of-they’re both equal pieces to this story, and because of where we end up, is is actually a hand in hand ancestral journey rather than a passing of the baton.

Noelle: Yeah, I think I think that impulse feels right. I mean. It’s interesting, I was having a texting WhatsApp conversation with my and my father’s cousin, who’s basically like his sister, because they were very close and my father was an only child and she kept kind of saying, repeating sort of that these two people that the characters are based on were really kind of halves of a whole, you know, and-and so I thought that was really interesting that they that she felt like they super complimented each other in that way. And it made me think a little bit about what you just said, that maybe there’s not like a passage to or from or even kind of like this ancestral like divvying up even though it is generations. I do think because both characters in the play are ghosts. Even before my abuelo died, he was a ghost in the sense that he lived in Uruguay which is a 10 hour flight from here in New York City. And so grief is also-distance is also a form of grief, you know. So in some ways, I think the generations get flattened in this story in in other ways that they get explored because both parties aren’t present. You know?

Galia: And I think on that beautiful note, we want to thank everyone for listening, for getting to know us more in our process, and we hope to see you at the Findings Series to share with you all of our amazing work and research and to follow the piece and The Civilians. Thank you Dante and Noelle for this great conversation.

Noelle: Thank you Galia.

Dante: Thank you Galia. Thank you Noelle.

Noelle: Yes. Thank you Dante. Alright, y’all. Bye bye!

To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, join our email list at TheCivilians.org.