Ten years ago, my mother went on Hajj — the annual pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia to visit The House of God. Over the course of five days, Muslims reenact key moments of the great prophets. By experiencing the place and prayers of these messengers and retracing their sacred events, pilgrims deepen their relationship to faith. Both spiritual and religious, Hajj offers a chance to ignite a deeper sense of love. It’s not only a rite of passage in Islam; it’s an honor.

On my mother’s trip to the holy land, she met a woman who coincidentally lived ten minutes away from her in Bridgeview, Illinois. They’ve been inseparable ever since. On any given night, my mother can be found in Tante Nariman’s living room, drinking coffee no matter the hour, watching Egyptian soap operas, eating nuts, and lamenting all that is right or wrong with the world. They celebrate holidays. They gossip about relatives. They seek one another’s advice on the most private of matters. My mom witnessed Tante’s eldest daughter bring a child into the world. She’s become a kind of godmother to Lulu.

But it wasn’t until a year ago I realized the significance. After spending time with Tante and her daughters in her home, I saw what was missing from my mother’s life—community. I’ve always sort of believed that community came naturally. It was family, friends, or neighbors. Community could be made at the gym or at work. It was fluid but usually within reach. For me. My mother didn’t have the same experience because despite the fact that she physically existed within these communities, I imagine she still always felt she was on the outside of them. I think for her and others like her who belong to two homes and feel foreign in both, community is very hard to create. With Tante, she found it.

Tante’s story is similar. She leaves Palestine for Illinois, endures a rocky marriage and raises children in America. They were both part of large extended families, a living legacy in their homeland. Back home everyone was connected by blood or tales of yore. But living in the Midwest was challenging in a new way. It was lonely. In an effort to create their own future, these two women both set sail for the greatest adventure of all — a life unknown.

My mother immigrates to Brooklyn in 1976 and within three years she marries my father, gives birth to me and brother, and files for divorce. The summer months we spend in Egypt eventually become more and more infrequent as the demands of a working single mom grow.

I can still hear America on my mother’s lips, that compelling brand for a country in the making recruiting the best of the best from around the world, quintessential slogans for life:

Anything is possible.

The price of success is hard work.

You can do anything if you believe it.

While her sisters were well into their second or third pregnancies back home, my mother was leaving work and running off to night school. One salary wasn’t enough for a family of three, but in order to make more money, one would need a higher degree and more certifications; these also cost money, but if it meant we could move out of our rental and buy a house in a better school district with a little left over to save it would be worth it.

If there’s a will, there’s a way.

Welcome to the land of opportunity.

Never give up on your dreams.

It took seven years but my mother managed the dream. She started as an accountant and eventually became an executive at an international shipping company.

As part of The Civilians’ R&D Group this year, I set out to research the lived experience of Arab immigrants. I began a series of interviews in Bay Ridge, a neighborhood in the southeastern part of Brooklyn, one of the largest Arab communities in the US and, ironically, my mom’s first home in America.

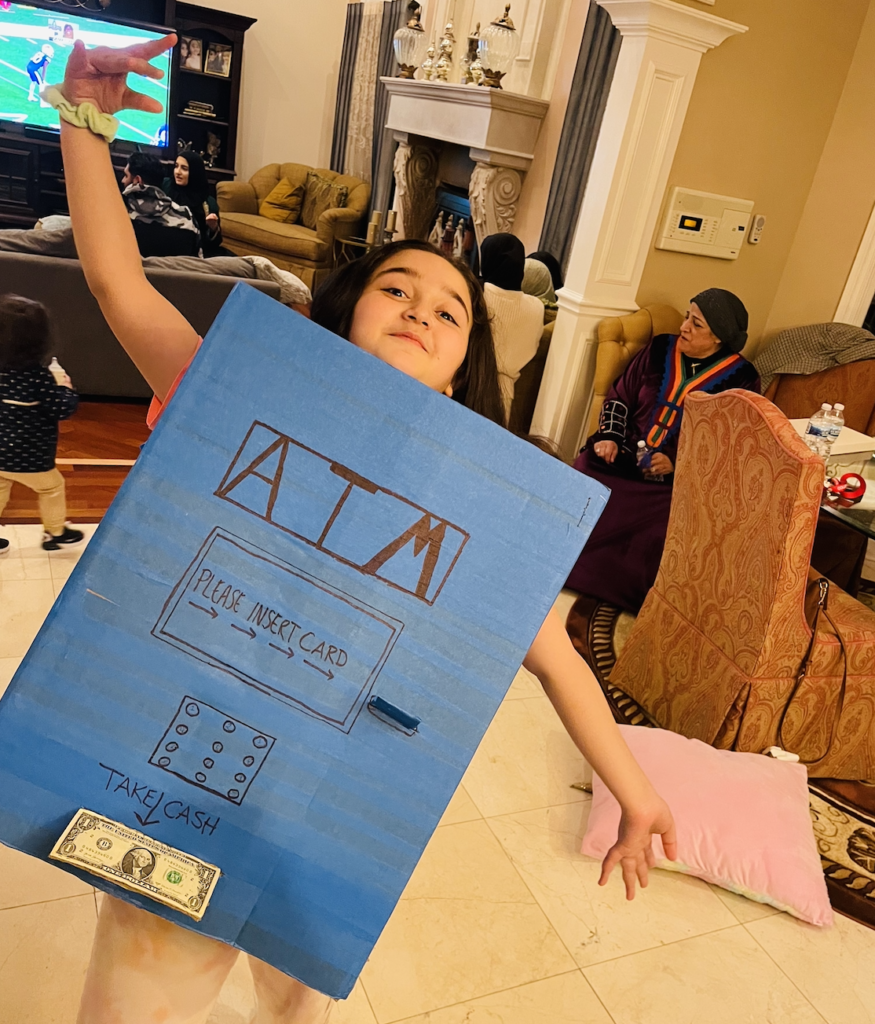

In focusing my research on Arabs in America, I soon realized in the interview process that the ones I was speaking to were actually American Arabs. This third-culture, born and raised in the city, certainly didn’t face the same issues of my mother’s generation. They also weren’t dealing with the issues of my generation, made up of overly ambitious kids frantically focused on the goal no matter the outcome. I was connecting to a third-wave generation of kids who were fluent in two cultures grappling with a conviction particular to their own age.

The people I interviewed were between the ages of 9 and 26 years old. Many had never been to their parent’s homeland and yet they were cultured, bilingual, politically woke, spiritual, and religious. This younger generation of Americans were deeply invested in their two cultures and were not interested in identifying as one or the other. They were clearly both. I’ll admit that at times I had to rewind the tape and slow it down to catch their phrasing and lingo—a combo of street hype, Arabinglish, and current affairs. After playing back hours of digital tape, I started to look for the thread. What was the right balance between invention and verbatim? How could I edit and revise to reveal the meaning underneath the text? What structures would lend itself to a story that was not linear, but panoramic? What was the story?

Sometimes when you write a play, even if you don’t know exactly where you’re headed, the reason why is clear. It’s this why that often compels a writer to commit pen to paper in the first place. But in this case, I started with an investigation—to become intimate with a particular community in Brooklyn. There was no goal, no hypothesis, no agenda.

People often think that writing is about writing, and it is, but it’s also about listening. Listening to this community’s stories changed me. It inspired a deeper quest into understanding the American construct of the Arab identity—legally, morally, and emotionally— but also the power of community to heal the soul of an individual. It became a process in exploring self through a collective voice. It’s been an honor to gather these stories, imagine a new world, discover a narrative and play. If you’re in New York on June 28th, I’ll be presenting the first draft in the Finding Series. I hope you’ll join me.

Hailed by the San Francisco Chronicle as “a tower of strength in the Bay Area theatre scene,” Denmo is an American playwright, actor, author, and entrepreneur of Egyptian descent. A Sundance Theatre Lab and Rainin Fellowship Finalist, her work has toured to international festivals in Cairo, Berlin, and Loire Valley, and to parks, black box theaters, and universities throughout the U.S. Her children’s book Zaynab’s Night of Destiny will be published by Fons Vitae in late 2021. Her next writing project is a ten-part historical drama for Audible. Denmo holds an MFA from Naropa University. denmoibrahim.com

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

Hailed by the San Francisco Chronicle as “a tower of strength in the Bay Area theatre scene,” Denmo is an American playwright, actor, author, and entrepreneur of Egyptian descent. A Sundance Theatre Lab and Rainin Fellowship Finalist, her work has toured to international festivals in Cairo, Berlin, and Loire Valley, and to parks, black box theaters, and universities throughout the U.S. Her children’s book Zaynab’s Night of Destiny will be published by Fons Vitae in late 2021. Her next writing project is a ten-part historical drama for Audible. Denmo holds an MFA from Naropa University. denmoibrahim.com

View all posts