Sylvia Bofill‘s recent play, La Erre is both a tribute to Puerto Rico’s buried history and an offering towards its present and future. Following the story of Teresa, a woman traumatized after her experience of violence in both PR and New York, Bofill weaves a story of familial wounding, colonization, grief and the messy possibility of collective understanding. In the following interview, Bofill discusses multi-disciplinary theatermaking, story-telling, and of course, the letter “r.”

I want to talk to you about the history of La Erre as well the experience of doing it recently. But before that, could you say a little about how you found your way into theater and the different hats you wear? I think I saw that you directed this piece.

I used to direct a lot when I was in Puerto Rico. I actually studied literature there, and then I studied theater and dance. Choreography is really important to me. I worked with the important Puerto Rican choreographer Petra Bravo, who works a lot with dancers and movement actors, so I was very influenced by her. Then I started writing and directing, and I was actually looking for a program that would let me do both playwriting and directing, but I couldn’t find one. Programs like that were mostly in Spain, and one I was interested in was in Catalan, and I don’t speak Catalan, even though my family is from there.

I was interested in the MFA in playwriting, but also in directing. The year I was accepted was also interesting; they called it the Puerto Rican Mafia. One of us was accepted in acting, I was accepted in playwriting, and another in directing. We got to know each other more there in the program.

I had already directed my work in Puerto Rico, but when I went to the program, I started working with Javier as an actress in his directing program, which was a very interesting experience. It was great because as an actress, I got to go through the [acting] program. You prepare for the scenes and see the feedback from Anne Bogart and Brian Kulick. I felt like I went through the whole thing and got a lot of their feedback. Other directors in the program also saw me acting and wanted to use me in their work, so I was acting and writing in the program.

Can I ask a mini question in the middle of this? I don’t know if it’s an American thing, but there seems to be this intense focus on specialization here, and I’m curious why that is. When I engage with theater makers from other countries, it’s very natural for them to say, “I’m an actress, a director, a writer, and I make puppets.” Here, I feel like it’s frowned upon, and everybody has their little thing, which they’re very protective of, and people don’t take you seriously if you do more.

Yes, it’s interesting. I think that’s one of the reasons why I came back [to Puerto Rico]; I felt myself a little bit too pigeonholed. In the Caribbean, South America, and even in Europe, it’s organic to write and direct your work or act. Right now, I’m much more focused on writing and directing, but all my experience in acting makes my writing better. That was something I found very unique to my experience. In New York, sometimes people are like, “Oh, you went to school for writing? Oh, you also direct?” They found that to be a little bit bizarre, but I find that very natural here at home.

I think it has to do with the way we conceive theater. It’s not something new—if you think about Shakespeare, Molière, or even the Greeks, they directed and acted in their own work. It’s interesting to be a writer and also know who you’re writing for.

One of the first playwrights who influenced my work was from Argentina, who worked in Ecuador. They always talked about how when you write, you have to put up your work because it’s not until you stage it that you see it come to life and take form. For me, it was always about writing scenes and then putting them up on stage. I enjoy those processes a lot. When I write, I think about how the text stands by itself on the page. Then, once I direct, I put on another hat, which I really love. When I direct, it’s more about painting, composition, and dancing.

I find that people with a choreographic background look at staging not just in terms of emotion but also as a visual element. It is very much like painting. With dance, the relationship to the bodies on stage is very different—more controlled and specific. I think there are so many ways to look at staging, and having that choreographic framework is beautiful.

I studied Comparative Literature and had professors of classical theater and classical literature. But on the artistic side, I had experimental dance theater professors. My work is a combination of both worlds and trainings. When I was in New York, one of the things I wanted to do when I came back was to direct my work. I’m always open to other people directing my work, but I enjoy the process of writing my work and then putting it up myself.

A director has a truly editorial voice. When you direct, the music, the color of the costumes—it all gives the piece another semiotic layer. I remember once in a talkback, an Argentinian director said that he ended up directing his own work because sometimes, as a playwright, he didn’t like the way others were putting it up. You want to see your piece put up how you finished composing it on stage.

As a writer, I take it very seriously that the text has to stand on its own, even if I’m not directing. Once I start directing, it’s interesting because you sometimes work in contrast: what’s already said in the text, I shouldn’t say with the body. I also think about writers like Sarah Kane, where the stage directions are movement and are so important you can’t take them out. As a director, you have to interpret those stage directions, sometimes in these cardiac ways.

With this piece, I did the first two drafts in English for the students, thinking they might put it up. (I wrote it in English because we thought it would be produced first in nY) The third draft, I translated to Spanish, changed the form, and edited it. It’s important for a playwright to see the actors do it. The rehearsal process was about editing, not just changing scenes. Putting it up makes you see what’s urgent. You want it to be urgent and find different ways to tell the story because now the body and other elements are also speaking. The play went from 120 or 130 pages to 82 or 85 pages. It was much more about editing than rewriting. It became more concise by realizing what was already being said. We noticed we would say things a couple of times without realizing it, but with the transitions and the staging, we realized, “Oh, this has already been said. Why do I have to say this again?” That was great. If we were to do it again, I’m sure it would be edited again.

I read a version of the play in English!

You read the second draft?

Yes, the 122 pages. I do have questions about that, and I’m curious to know what you condensed.

For example, there are scenes in the play—like the street—that for me were ellipses. When directing, I noticed the street becomes a choreography that creates an ellipsis of time. You see characters coming back and forth, and she’s walking through the streets. That transition makes you understand, “Wait a second, we’re going back in the past, or we’re going back in the future.” That already happens in the text—it says she’s walking on the streets and cars are illuminating her body—but the way I staged it made the other sense of time and the choreography clearer. Now, the question is how to incorporate that staging information back into the text. You have to decide if you add something that made the play better in directing, even if it wasn’t in the original script. I think I would add the street scene where the play begins with her in the center and characters walking by, even though the text currently starts with the hospital scene.

This is so interesting because when there’s a clear distinction, like “I’m the playwright” versus “Someone else is directing it,” playwrights sometimes negate responsibility. They create the world and motifs and are like, “Great, the director will figure it out.” It’s fascinating to hear you talk about putting all the pieces together and asking, “Is this a problem I can solve with directing, or does it have to be solved via the text?” That’s complicated with two different people, never mind when you’re the one person making all those decisions.

It’s interesting because in New York, it almost felt like it was a bad thing if the playwright directed their own work. They felt you wouldn’t be able to see it differently, but I feel like it’s the opposite. It depends on the type of playwright you are and if you have experience on stage. I think it’s okay for different types of playwrights to exist—you don’t have to be a playwright who wants to direct their work. I agree with you that the street motif repeats itself and became much more fleshed out in the directing process, which I would add to the text.

Other things, I wouldn’t add. For example, I created the scenery with wheels so the whole set was very movable. I might leave that to the director; it was very important for what I did, but I don’t think I would add it to the play’s script. The way you used “motif” is exactly the word I use. The street, not in a literal sense, but the sound, was very expressionistic. It didn’t take you to a specific street, but to this non-realist place. I would definitely emphasize that the sound is expressionistic in the script, as it became an important character, often taking the audience to the point of view of Teresa or other characters.

Where did the impetus for La Erre come from? What questions were you asking, or what was turning around in your mind? When I read the draft, I was thinking a lot about the investigation of the “model immigrant narrative”—that you come to America and everything is automatically better. I think life is more complicated than that.

I wanted to approach a political theme through a very personal lens. How do we see this political trauma or wound through the life of Teresa and her son? I was really engaged with people in my personal life ending up on the street. People see someone on the street but don’t know how they got there. We have a long historical situation in Puerto Rico, even before the US, with Spain, and I think it’s rooted in our bodies.

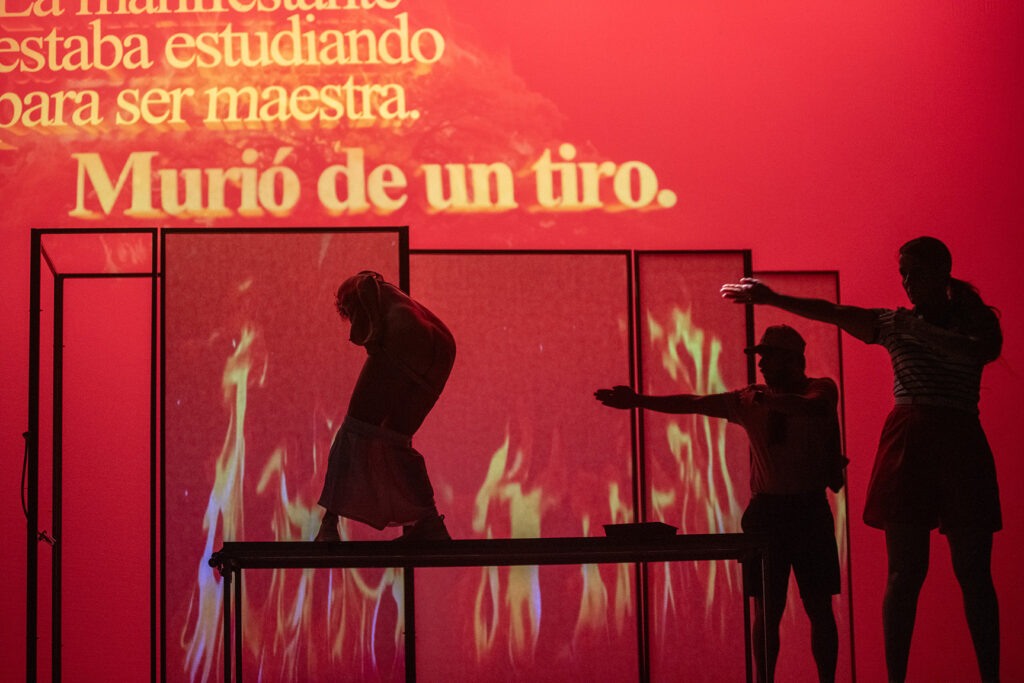

I was interested in this political activist and the contradiction that happens to so many Puerto Ricans: you end up in the United States, but that doesn’t necessarily mean fulfillment. What happened was this ex-activist was censored in Puerto Rico, lost her job, and ended up in the States. At some point, the mental breaks hit her. Dramaturgically, I wanted to work with someone who’s paralyzed at the start, and then in the last scene, you see her in total movement, full of hope as a young student, a protestor.

That scene was incredibly heartbreaking to read, because by the time you get to the end, you have most of the information, so you know what’s going to happen to her, and she doesn’t know. It feels very Greek in that sense of tragedy.

It’s heartbreaking because the audience knows. I was surprised by the audience response because I had three generations: Teresa’s generation, Gen X, and the younger generation who connected to Jason. The story of Antonia Martínez is one that happened in the 70s, and not everyone knows about it anymore.

Nobody wants to talk about it, I imagine.

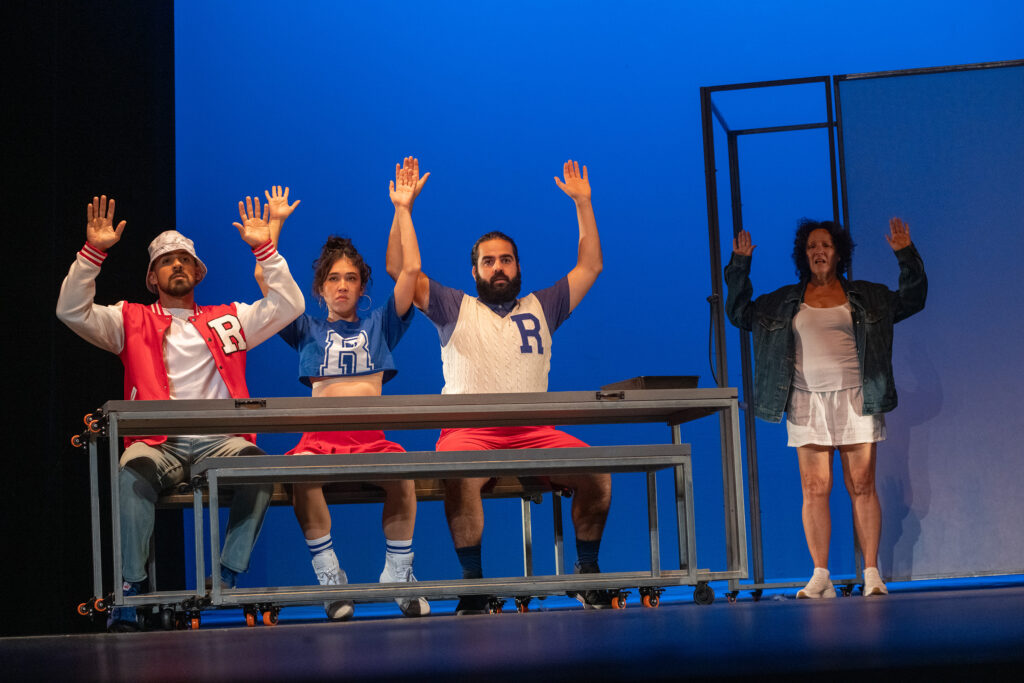

Right, exactly. We were worried about how to publicize this because I didn’t want people to think it was just about Antonia Martínez. It’s important, but like her, a lot of political things in Puerto Rico have been buried. We actually did the play out of order for the actors to understand the chronology for themselves, but the play isn’t told that way. For me, it was very important to go from seeing this woman who is totally controlled—and I meant that in a very patriarchal way, with men taking control of her body—and then going back to when she was full of movement.

Of course, the ending, when she’s full of life and wanting to change the world, is tragic because we know what’s going to happen the day after that. But the ending is reflective; it makes us wonder, “Where are we now?” I didn’t want the play to end with a resolution. Directing-wise, it was interesting because I mixed realities—past and present. The final scene collides Ramon and Teresa in the past with the brothers walking in. The table, which we understood to be the coffin, is taken away as Teresa and Ramon leave, so we understand the past and present simultaneously. For me, it was about how we go through the story of this person, and while the audience may not know the exact chronological order, they start to understand her mental breaks.

The nature of trauma is that the past and the present do collide, and you can’t tell what is happening now versus what was happening in the past. The logic is sound, or dramaturgically, it makes sense because you’re experiencing things the way Teresa is also experiencing them.

I wanted to connect the past to what’s happening now, like how our land is being sold due to Law 20, where investors buy cash in order to be exempt from taxes and a lot of people are being affected. I feel there’s a connection between the 70s and now.

I was thinking about that artistically, too, in terms of people being multidisciplinary and experimental. The 70s were a time when that was certainly happening in the US. But I also think about the trauma people were experiencing and how that legacy shapes the present. What parallels do you see between the 70s and now in Puerto Rico?

What triggered Teresa in the play, in the fiction, is the police brutality happening in New York, which triggers her because that hasn’t stopped since the 70s. It’s interesting that we opened this play, and the week after, the military came to Puerto Rico. Now, the US is preparing a front–similar to what they did with PR in the past when they started militia exercises to develop a strategic base in the Caribbean. It was so weird that this happened because, in the 70s, people were protesting against the ROTC and the militia in the university, fighting against Vietnam. We put up this play, and a week later, it seems history repeats itself. Police brutality is still happening, as are things with ICE. I wanted to connect what’s happening right now in Puerto Rico to what was happening in the 70s, even if it’s through a different lens.

The play felt very current. The reaction of the audience was interesting. A lot of people from the 70s generation felt their lives had been shattered, and they went to the United States for a better living—the American dream. But in the play, we were not seeing the American dream with that same light.

Regarding your question about what was edited, sometimes when you’re writing, you’re generating, and then you realize things are already obvious and don’t need to be said. More than rewriting, it was about editing what was overwritten. The actors really helped me with that. When you see it up on stage, you realize, “Oh, this is kind of awkward.” Readings are great, but at some point, you have to see it embodied. We needed to cut where the story was being overwritten.

Also, trusting that the audience will know and can pick up what’s happening. I wanted to ask a question about Ramón, the father. I assume the scene is still in the piece?

That was one of the scenes that was very cut.

In that scene, Marcos is continuously asking him, “Why did you leave? How could you leave?” and his father never answers that question. I found something so striking about that. When you talk about these experiences living in the body and not being able to process them, leading to these breaks, I wonder if there is a way forward.

I think one of the characters who is definitely moving forward is Marcos because he’s putting things together. The scene was cut a lot because there was too much storytelling, and you don’t want to keep listening to a story right at the end. Marcos is trying to understand his mother and himself. I left what I felt needed to be said about his father, who Marcos is surprised to learn wasn’t just a drunk but was a surgeon whose whole future was crushed. This happened to a lot of people here. I had in my hands the “files” (carpetas)—political files the government created in the 70s to follow all the left-wing activists.

Wait, what files are these?

In the 70s, the government created these political files where they basically followed left-wing activists. It’s similar to the McCarthy era with the communists. Different agents would follow politicians, tap their homes, and interview people, and some would be spies. Eventually, these files were disclosed in the 90s. It was horrible—people found out their neighbors were spying on them, or they were fired from jobs because of the information in the files. Some even found out they had married an agent.

A lot of people realized they never got a job because of this. I interviewed people close to me who went through this. Part of the play is actually based on a true story. I interviewed people who were fired from their jobs and expelled from the university after the protests. Agents would go to their bosses and get them fired repeatedly until they left the United States for a while.

I wanted to talk more about Ramón in that scene, but we’re at the end of the play, and a lot has happened, so I didn’t want it to be so focused on storytelling. But Marcos’s question was important. I think he is coming to peace, putting the pieces together, and understanding his father’s history. That scene became very dreamy because you don’t know if it’s the scene he always wanted to have with his father. He’s asking his father these questions while his father is dressed and in his twenties. I cut it to focus more on the father in that moment, making it more condensed and symbolic. It’s about Marcos trying to come to terms with his father and himself. Not having all the answers is part of his journey, and when you understand your past more, you can move on.

The other interesting thing was that people got the fact that Teresa, whom we see through a personal lens, also becomes metaphoric: PR is a paradise that, like Teresa, is also being violated. They could see she was both a person and an allegory for Puerto Rico. I wanted to work on those two levels, and it was possible.

That scene where she comes out, though we cut it a little, I think it shows so much more about what happened. The way it was done, when Teresa comes out almost naked, taking flowers out of her body… the audience would gasp. That moment was important; you see this body that is vulnerable and has been used.

Your description is making me think of Ana Mendieta’s work—the body, the Earth, the woman’s body being represented.

Definitely a connection, because her body is so much a part of nature. But then sometimes, she’s not there anymore.

Right, the disappearing that’s happening, which Teresa is going through, disappearing from the present and from her time on Earth.

I have to say her acting was great. What also helped is that while the play implies her presence, the fact that she is always on stage creates a different meaning. Her presence is there, even though she doesn’t say anything. I wanted to work with an absent presence. Maybe she’s just in the bed, or the lights are off, but she’s there. The through line became clearer with the physical presence of the actress, who works a lot with her body, like a dance-theater actress. She’s very present in general. She’s the perfect actress for that because she works with performance and solo stage work. Seeing her on stage is different than reading the play, where you might not realize that the character is still there. These things became more evident in staging.

Is there something you hope people might leave with after seeing this play?

I think I really wanted them to go through this back and forth and ask questions about where we are today. I wanted to pose this political question and explore it through a personal lens. Sometimes, you understand things better through a personal lens. It’s like when one of the characters has sex with a sex worker; he doesn’t think about it, but once he realizes its his mother, all the shame happens; it becomes personal. For me, it’s about whether this trauma, this memory, this sense, was connected for the audience.

At the same time, the title of the play, “The R,” appears as a sound or a word. On stage, we worked on it as a sound, saying it with fury or softly. What does that sound transcend? For Teresa, it means her fury and what makes her move/protest, voz canina (“a growling voice”). But that “R” has so many connotations for us and for people. We use the “R” the way we want to; words are ours. We transform them. When people see the play, especially the staging, they start asking, “What is ‘The R’ for you?” I was interested in what people think “The R” is in the end. It’s not literally said throughout the piece: it’s heard, and it’s seen in the body. Jason talks about the origin of “The R,” but it’s something the audience begins to see throughout the play. For me, it was important how people understand what “The R” is for them.

It’s interesting to think of the symbolism. With the French “R’s,” there’s a colonial aspect as well. But thinking about this “R” as a big part of the Spanish language brought to Puerto Rico through force, it’s this legacy of, “Okay, we have this thing. What are we going to do with it? Are we going to remix it?” When Teresa talks about how sometimes people get rid of it or make it sound different, I love that so much. I feel like that is the heart of it.

And that’s us as Puerto Ricans. Like Teresa says, “Dile a Mario que nosotros somos piratas y que cambiamos las cosas como nos da la gana” (“We’re like pirates. We change things however we want.”). The sound of the “R” comes in different moments in the staging. It’s heard throughout and has different meanings. It’s something that runs throughout the play in a much more sensorial way—sound, movement, and what they talk about. People keep asking, “What do you think ‘The R’ is?” It remains a question in the end.✦

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.