On my first night back in Durham, North Carolina, Jon Haas, a friend of mine and a talented video designer, invited me to “Habitus,” an interactive installation that he had created with his collaborator, audio documentarian and choreographer Leah Wilks. Their investigative performance company, Vector, was closing up their residency at Durham’s Manbites Dog Theater by creating an experimental installation of “Habitus,” a piece exploring anger and violence, before producing the stage version a few months later.

I attended the event with Manbites Dog’s Artistic Director, Jeff Storer, and from the second we walked through the doors of the lobby and handed our tickets, my hackles went up. There were two questions printed on the ticket to get into “Habitus”:

Are you an angry person? Circle yes/no

Are you a violent person? Circle yes/no

I was irritated with the pointed lack of distinction between anger as a feeling and anger as an identity. I circled “no” for both, but then spent an inordinate amount of time second-guessing that decision, as if this was some kind of test I could fail.

After we received our tickets, we were ushered through a seemingly endless check-in line, with various tasks to complete at each station. Jeff and I were handed medical charts attached to clipboards, and were asked to draw on two human figures where we felt anger in our bodies. A TV in the waiting area cycled through clips from the news, recent disturbing footage from the Ferguson riots interspersed with images from professional sports and pop culture. When we were done with our paperwork, our drawings and ticket were then scrutinized and stamped by a bureaucratic-looking woman at a desk. Watching her casually scan my drawing felt oddly intimate, but I tried to hide my discomfort. A man in a suit flitted up and down the line, telling us in fluent customer service-speak to let him know if he could help us with anything. (However, his overly friendly veneer and panicked smile suggested that he would be relieved if we didn’t ask him anything too difficult.) A girl in a skimpy outfit picked out costumes for us and insisted we put them on. My friend and I were then made to pose as if we were in a knock-down drag-out boxing match with each other and our picture was taken. We were “good sports,” acquiescing all-too-easily, but letting someone else control how I looked and acted and then recording the result left me feeling vulnerable and violated. Lastly, a gestapo-inspired security guard type policing the entrance to the installation checked the stamps on our papers again and barked orders at us, telling us to stand against the wall and not cross the line — basically treating us like criminals.

“By the time we were granted access to the main part of the installation I was a tense, triggered mess, vibrating with silent rage.”

There is no way to know what an individual will find triggering or anger-inducing, but Vector had been incredibly thorough in their inclusion of a variety of scenarios. I have to say, as a woman who is sensitive to how she is photographed and portrayed, an Eastern European Jew who has a Holocaust-induced cultural terror of security checkpoints, and a person who has experienced chronic illness throughout adolescence and early adulthood (and the casual physical violations that result from interacting with medical bureaucracy), “Habitus” was like the perfect anger-inducing machine for me. On their own, each action might have seemed innocent, habitual, or harmless, but strung together these interactions were grotesque and overwhelming, a virtual buffet of microaggressions, cloaked in the guise of bureaucracy and administration. By the time we were granted access to the main part of the installation I was a tense, triggered mess, vibrating with silent rage.

I stumbled numbly through the rest of the installation and breathed a huge sigh of relief when Jeff and I finally escaped out of the side doors of the theater and into the night air. I fired off a quick passive-aggressive text to Jon (“Thanks a lot. I need a whiskey. And a hug.”) and proceeded to try and shake the discomfort and rage I was feeling.

I had no idea what to expect from “Habitus,” but I found myself deeply unprepared for the emotional response it provoked in me. Even thinking about answering those two deceptively simple but provocative questions made me incredibly defensive: Are you an angry person? Are you a violent person? Having grown up in a household with a parent who had an unpredictable and often violent temper, I became a master escape artist when it came to anger, both of others’ and my own. In my experience, angry people were dangerous people, and I had worked really hard to avoid that danger. Am I an angry person? I spent a lot of energy making DAMN SURE I was not.

A few weeks later, I finally met with Jon to talk about “Habitus.” Much to my horror, when I talked about my experience walking through the piece, I began to cry, and much to my surprise, when I looked up from my drink I realized that Jon was crying too. It turned out that starting the conversation about anger doesn’t make you immune to the effects of that conversation; if anything, the responsibility of helming such a controversial and personal investigation weighed more heavily on him than it did on me. Every night of “Habitus,” Jon had anonymously watched the audience walk through the installation, finding it overwhelming to process the myriad of reactions it provoked in each of them: some laughed and goofed around, some shrugged it off and looked bored, others actually got angry and lashed out. I wondered how many people had silently imploded like me.

I asked him what drew him and Leah to exploring the topic of anger. He explained, “Anger is a facet of what it is to be human, and it’s weird how we fight against that and try and remove ourselves from that. I get angry at times, and it can be a little scary. But I still think there is a place for it. And that is worth discussing… Like is there ever a situation where violence is okay?”

That question is a controversial one. By all accounts, our country has had a very violent year: The police brutality and racially-motivated violence committed in Missouri, New York, Florida and Baltimore, and the protests and riots that followed are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to our cultural anger. Anger-induced mass shootings have become so common, that it’s a rare week when we don’t hear about a person dealing with their rage by going on a shooting spree. In America, anger and violence are as intertwined as they are dangerous: an angry person is a terrorist-in-the-making, and anger comes with its own body count.

However, the dangerous flip-side of our culture completely renouncing anger and violence, is that our relationship to darker emotions remains largely feared and unexplored. Leah Wilks, the other creator of “Habitus,” said, “It’s really easy to be judgmental and compassionless towards perpetrators of really atrocious things when you don’t see that ability in yourself and I think often we label other people as ‘angry people’ or ‘violent people’ instead of people who sometimes get angry or sometimes get violent.”

Leah, who grew up in a relatively peaceful household in North Carolina and attended Quaker schools her whole life, found herself curious about her own seemingly nonexistent relationship to anger. “I was raised as a woman in the south. So even though I was raised in a pretty alternative environment, there’s a certain thing about ‘being nice.’” When she studied abroad in Botswana, she was shocked to find how peaceful the culture felt. “I never felt threatened, never felt unsafe, but I also felt bored! Art was about ritual there, which was really wonderful, but you stepped over the border into South Africa and art was rampant and really intense. So I started thinking about my own desire for conflict, and if that made me a really fucked-up person.”

Leah shared that her fascination with anger and violence led her to live at a punk-anarchist house in Durham. Throughout the year that Leah and Jon were creating “Habitus,” she often found herself participating directly and indirectly in the Durham protests of racial inequality and police brutality sparked in Ferguson. Not comfortable in the epicenter of the protests, often her role included bailing friends out of jail, but soon this role and other stresses began taking a toll on her emotionally, and this darkness began seeping into the artistic process. She confessed that she knew, as the director, she should leave her difficult emotions at the door, but inspired by their exploration of anger, she convinced herself to really dive into her own uncomfortable feelings. During a particularly hard week, she admitted to her company that she couldn’t take care of them that day. While the prospect of being that vulnerable and honest as a leader felt potentially dangerous and irresponsible to her, the bravery that it took to be that real and present in her feelings allowed for an even more trusting and naked collaboration with her actors. She said that the hardest and most rewarding part of the process was “being okay with being seen in the complexity of my ugliness.”

Processing my intense reaction to “Habitus” made me wonder whether I’ve been avoiding my anger and “ugliness” when it came to my own work. I certainly don’t shy away from anger-inducing topics; in fact, social injustice is at the heart of much of my work. And while I’ve definitely seen other shows that have awakened feelings of anger in me, nothing has stayed with me and haunted me like “Habitus” has. Perhaps the difference between the anger I felt that evening in Durham, and the anger that goes into my work, was how unprocessed and public it was.

“I don’t trust my own unprocessed anger: It feels messy and dangerous, and I can’t control the outcome.”

For me, the experience of walking through “Habitus” caught me off guard because I was being engaged in a two-way conversation about my own anger without the advantage of time or space to process it. And I don’t trust my own unprocessed anger: It feels messy and dangerous, and I can’t control the outcome. When I saw the stage show of “Habitus” a few months later, watching from a safe distance in my seat, I found it interesting and moving, but it didn’t trigger and enrage me in the same way the installation had. But that night, at the installation, through each interaction, I felt like a response was being begged, goaded out of me, to say something, to stand up for myself. I was given the choice between public anger and compliant violation, and I chose the latter because it was the only choice that didn’t seem unpredictably monstrous and woefully dangerous.

Perhaps my reaction to “Habitus” exposes more about me than it does about the effectiveness of the piece, but perhaps it is also a window into the bigger conversation about the potentially valuable role of anger in our culture, specifically in art-making. Does anger have a positive purpose in the creative process? In our lives? When I think of anger, I imagine a raging fire: full of energy, warmth, power, motion, and depending on how it is harnessed it can either generate or destroy. Anger is responsible for much death and destruction, but it can also be a powerful impetus and a force for change, and carries with it a lot of love, passion and investment. After I stopped trying to avoid and suppress it, my own anger told me a story about what I valued and cared about, what I stood for, what I would fight for.

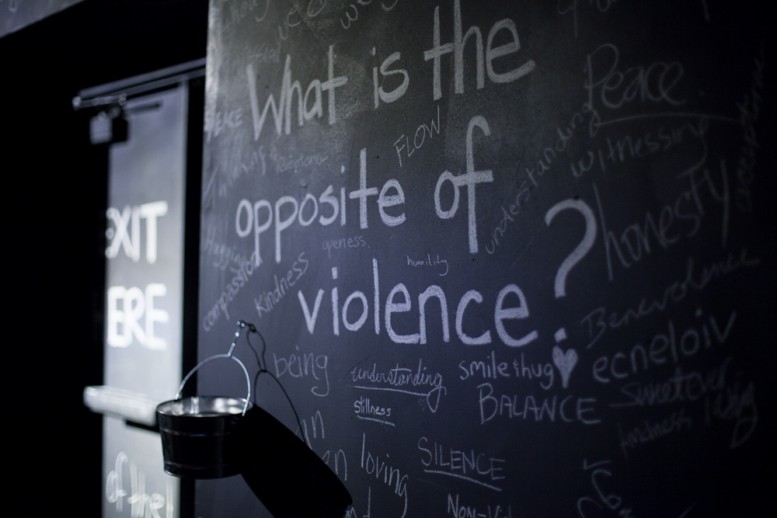

As part of the “Habitus” installation, questions were scrawled on walls and audience members were encouraged to add their answers in chalk. Some of our answers were really telling, exposing just how unexamined anger is for most of us. Leah observed, “On the wall where we asked the question, ‘What is the opposite of violence?’ somebody put ‘love’ and that was just so fascinating to me because love and violence are intricately interrelated.” When asked to answer if they were an angry person or a violent person, most audience members said, “no.” Leah and Jon were fascinated to observe that most people didn’t see themselves as angry or violent people, but when pressed, they could see themselves committing acts of violence if it meant standing up for something they believed in, or protecting a loved one. “So often,” she said, “Violence comes from a place of love.”

Author

-

Talya Klein is an award-winning director, actor, writer and producer whose work has been seen in London, New York, Los Angeles and all over the US. Directing credits include: "Grounded" by George Brant (Manbites Dog Theater, NC), "Enron" (Duke University Department of Theater Studies), "Failure: A Love Story" (UNC Chapel Hill Department of Dramatic Arts), "Cymbeline," "Much Ado About Nothing" and "As You LIke It" (The Here & Now, VT), "Born This Way" (BCC Rep, MA), "Parade," "All The Things You Are," "Three Sisters" and Aphra Behn's "The Rover" (Brown/Trinity MFA Program), "We Can Rebuild Him" (Brown University Mainstage/Brownbrokers), "Red Noses" by Peter Barnes and "Black Snow" by Mikhail Bulgagov (Kensington Drama Company, London), the American Premiere of Samuel Adamson's "Clocks and Whistles" (Origin Theatre Company, NYC) and the West Coast Premiere of Rinne Groff's "Orange Lemon Egg Canary." In addition, Talya has worked on staff or assistant directed at the National Theatre, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Pasadena Playhouse, Trinity Repertory Company, the Culture Project, Manhattan Theatre Club, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Weston Playhouse and the Public Theater. Talya received her BA in Theater and Social Struggle from Duke University. During her time there, she was awarded a Benenson Award, the Alex Cohen Award, the Dasha Epstein Playwriting Award, and named one of nine local "Artists to Watch in the New Millenium" by the Raleigh News and Observer. Talya earned her MFA in Directing in the Brown University/Trinity Rep MFA Program and is the founder of The Here & Now, a company which produces one-off, site-specific theatrical events. Talya was the Project Manager for the Civilians' Let Me Ascertain You: Holy Matrimony! at Joe's Pub in 2013. Last year she was the Lillian Chason Directing Fellow at UNC Chapel Hill and a guest artist and visiting faculty member at Duke University. Talya is a member of the Lincoln Center Directors' Lab and the Directors' Lab West.

View all posts