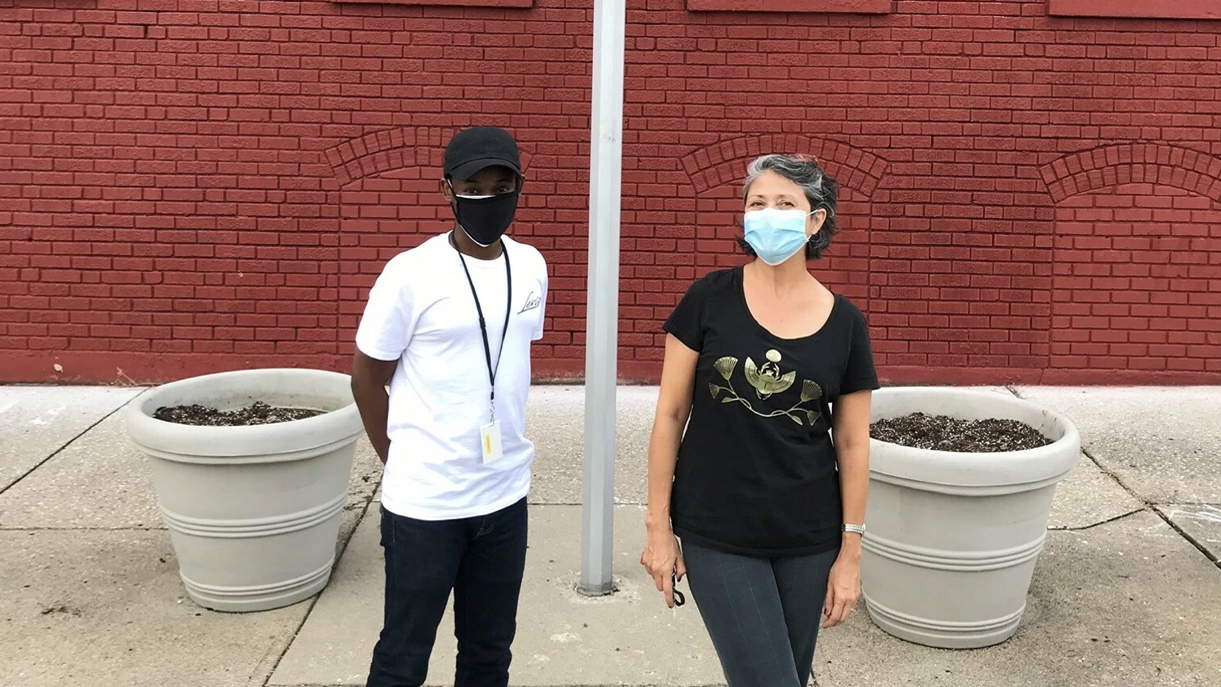

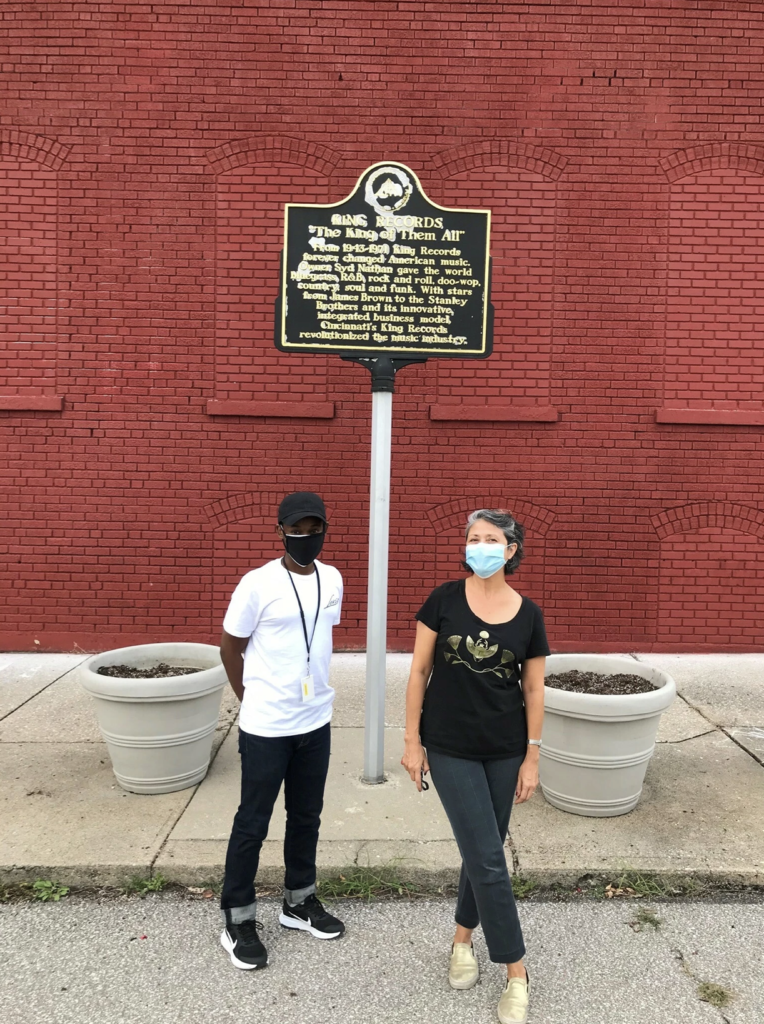

Documentary theatre playwright and director KJ Sanchez has spent nine years working on Cincinnati King and Need Your Love, two plays about a Cincinnati music label, King Records. Both plays were produced at Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, Cincinnati King in 2018 and Need Your Love in 2021. After nearly a decade of commitment on these works, Michael DeWhatley, a student of KJ’s and a playwright interested in plays about real events, wanted to speak with her about how she balances sense of place and representation in plays based on the lives of real people. What particular responsibility does a documentary theatremaker have to the subjects they investigate and represent onstage?

Michael DeWhatley: How do you negotiate the relationships that you have with the people that you’re interviewing?

KJ Sanchez: It helps to be a compassionate, nonjudgmental listener. A friend of mine is a therapist, and we talk about that occupational hazard, setting aside your responses and your own opinions and just trying to be compassionate. Let the other person go wherever they want to take you. Not having an agenda is everything.

Michael: Why do you think it’s important not to have an agenda?

KJ: Because it determines what they’re going to tell you. So, for example, yesterday I was rereading one of these interviews that I conducted with somebody who led the invasion into Iraq. If I had immediately come in with an agenda of prepared questions, the interview would have been jagged and clunky and tense because it would be clear that I was trying to pull something out of him. Because I had no agenda, he immediately just shared hours of his combat experience before we got to him talking about coming home. Even though we didn’t use a lot of that material, that builds the bonds of trust and confidence that allowed for the really great material that he then shared with me about coming home. I don’t think he would have been as candid, as trusting, if I hadn’t let him lead that conversation.

I think there are two different approaches to interview-based playmaking. We can be amplifiers or we can be takers. If it’s a one-to-one transaction, and if I come in with an agenda, I’m a taker. I am here to take your story and put it in my play. Or we can amplify a voice or an underserved community. We can provide a bridge to an experience for people who don’t know of that experience, and maybe they’ll get more invested and connect these disparate communities through amplification. That’s what we’re trying to do. And if we’re going to be takers, then we have to give back something.

I usually don’t pay interviewees because I feel like it is a conflict of interest, but with Philip Paul—who was the King Records studio drummer whose interviews were the foundation for Cincinnati King—I was a taker in that transaction. He gave me all these stories and all of this information, and I transcribed it and those transcriptions went into the play. However, he’s telling me stories of being a studio drummer in an industry that didn’t pay him royalties on all those millions and millions of dollars. Now I make a play about that exploitation, and it felt exploitive to me if I didn’t pay him. So, I gave him a percentage of the royalties. It’s a situation where I am hopefully amplifying, because this story is not really known very well. I’m recognizing that, particularly because I’m not from a Black or an African-American community, I am a taker, big time, in this process.

Michael: How much of your work would you say is developed in the rehearsal part of the process?

KJ: 70 percent. Leading up to it, I’m doing tons of drafts. But those drafts are really just building blocks. Then, in rehearsal, I have note cards of every moment in the play. I go back and chop up all my current drafts into little pieces, and then they’re tacked on my walls, and they’re on the floor. And any given day, I will move the pieces of the puzzle around, and we’ll try it and have a conversation. Somebody will bring in something that’ll blow my mind. Then, I’ll go back and rewrite that night.

Michael: So, it sounds like your work is an ongoing process.

KJ: Yeah, it keeps… for instance, with ReEntry, the play I wrote with Emily Ackerman about Marines returning from combat deployment, we did a lot of revisions from its premiere at Two River Theater to its New York run. I think we revised probably 35-40 percent of the text. In New York, we started to understand what it was. And when it was going to military bases, there was another revision of it. But other pieces have had much longer processes. Highway 47 gets rewritten every time I do it, every single time.

This idea of writing something universally is like, the audience becomes just like a blank canvas. And it’s harder for me to write for them.

Michael: When you’re making something for a specific place and time, do you find yourself thinking about ways to make it more universal?

KJ: I just give in to my love for writing a piece for the moment.

Michael: Do you think the Cincinnati version of Cincinnati King could have done a tour and it would have been fine as it was?

KJ: I think it would be a perfectly good night of theatre, but for me that spark of joy is writing the one little line that only the audience in Cincinnati is going to get and appreciate. That makes me so happy. And maybe my problem with writing things that will get done by everybody is when I’m writing, I’m envisioning a very specific audience member listening to it. This idea of writing something universally is like, the audience becomes just like a blank canvas. And it’s harder for me to write for them.

And then we’re living in a moment where rightfully we’re all asking, “Who has the right to tell the story?” Where are you sitting with that?

Michael: One of the questions that I’ve been asking myself is, “how much of myself am I putting into this work?” Because as I was writing this play about the five nights of sanctuary in First Unitarian in Louisville during the Breonna Taylor protests in 2020, I found myself feeling that part of me was very much in this play. It spoke to my religious tradition, where and when I lived in Louisville, my relationships with some of the people whom I interviewed. I was like, “I don’t know if it is appropriate for there to be so much of me in this piece when I wasn’t there.” And while I interviewed a diverse group of people, this was a protest about Black lives. So I tried to emphasize the parts of the story that were surprising and startling and contrary to my experience, and to take out some of the stuff that felt familiar and more about me than about the event that I was describing.

KJ: I think that it’s perfectly valuable to put yourself in because you provide the context. When I’m your audience, it helps me understand how the information is being delivered if I understand something about who has been capturing and amplifying it. There’s a solo piece that I do called Highway 47, which is about my family and the land feuds in New Mexico where I grew up. A lot of the first drafts of that play didn’t have me in it because usually one of my core ethical compass elements is that it ain’t about me. So I was telling this story, and every dramaturg, artistic director, everyone said, “It would help if you put yourself in this story because we’re here to see you. You’re our entry point into this.” Culturally, we put a lot of value on first person experience.

Michael: How do you put yourself in your work without having an agenda? I think one of the things that I struggled with in the piece that I wrote was how I did not feel the need or desire to include a contrary perspective. I’m thinking about the role the Baptist minister plays in The Laramie Project, as a character who explicitly condemns or counters the larger narrative of the work. I did not feel it was necessary in the story I was telling to have the perspective of a cop.

KJ: Yeah, I think we are done with those false equivalencies. If you were doing a play about a single car accident, we would want to interview the drivers of both vehicles because both drivers have equal weight, leverage, access. But if we’re looking at any given experience that involves power, access, knowledge, information–no way the two sides have equal value.

Michael: I read the drafts of Need Your Love, the play about the life of singer Little Willie John that you recently directed and wrote for Cincinnati Playhouse. You sent me those drafts before rehearsals and after. Do you feel like that piece evolved a lot over the rehearsal process?

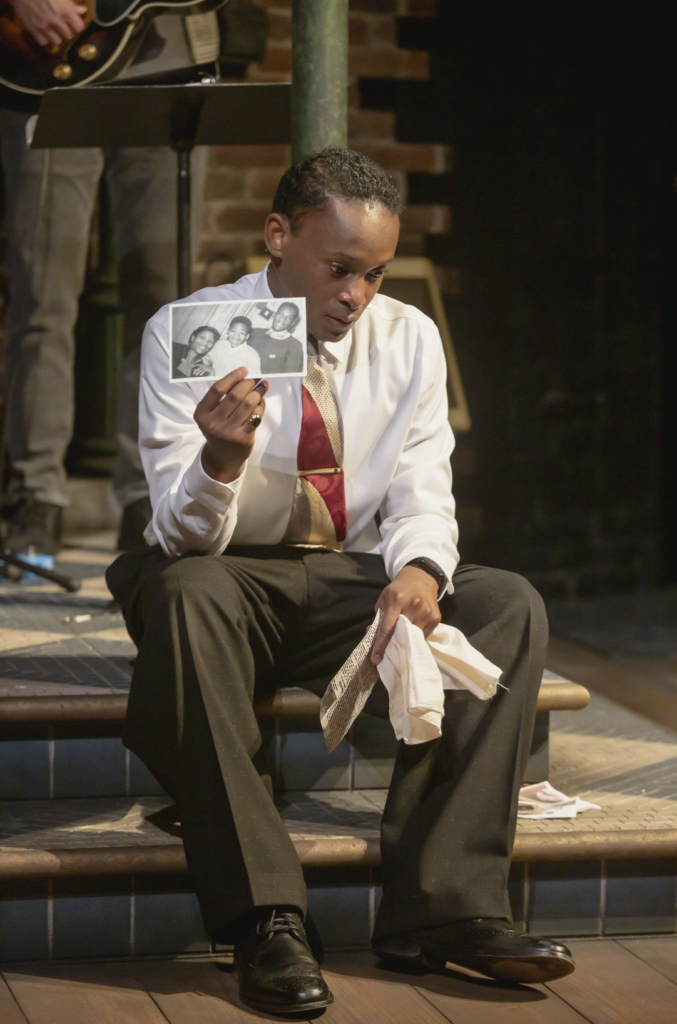

KJ: I think the end is where it’s most different. Willie John died in prison at the age of thirty while serving time for a manslaughter charge. There were conflicting witness statements, and even the prosecutor questioned whether Willie should have been found guilty. My intention was to uncover the definitive truth about what happened to Willie, but I was never able to. I finally realized that I needed to acknowledge–in the script itself–this problem. Bio-plays are tricky because people watch them and believe that what they are seeing is what actually happened. And we (the writers) often don’t have all the puzzle pieces. We have some, and we try to paint a picture from those puzzle pieces, but odds are, the information is incomplete. So I left the ending open to interpretation and made clear that what the audience was seeing was stitched together from boxes of memorabilia, spotty reportage, and conflicting eye-witness accounts. And by doing so, the play really became about how we tell somebody else’s story.

The play was also highly informed by Antonio Michael Woodard, the actor who played Little Willie John. A few clutch moments came from him, his ideas. He grew up in the church. He played drums and sang gospel all his life. So the play is more spiritual than I expected it to be because Antonio is a more spiritual person. I think it’s also because Mable, Little Willie John’s sister, who I interviewed for this project, is also spiritual. That’s where I didn’t expect the play to go, being about faith and spirit and peace.

Michael: Did your relationship with Mable evolve over the course of the process?

KJ: Yeah, it did. It started with her not holding back in letting me know she thought I was full of shit. So it went from that to our next couple of conversations, which became more warm, because I think we started to get to know each other better. It’s interesting—I wrote this, in many ways, for Mable. The KJ ten years ago would have bristled at that idea. You’re supposed to follow your own artistic impulses. It isn’t about making any of the stakeholders okay with what you’re reflecting. If I was sharing something that a community wasn’t happy with, my response would be, “It’s like a photographer taking a picture of a fire. You can’t accuse them of arson. They’re just sharing what they see.” I used to be very strident about how reflected what I saw, in whatever capacity. I’m still true to that set of ethics, but working with her was a really interesting driving force.

Bio-plays are tricky because people watch them and believe that what they are seeing is what actually happened. And we (the writers) often don’t have all the puzzle pieces.

Michael: It’s an interesting progression because Need Your Love has gone from something that was community-led to something that was artist-led to something that is now, in a way, dedicated to a person. How do you know when you’re engaging with a community that’s uninterested in participating in the way you normally work?

KJ: There were two times when I had any kind of friction with the community. In one, the main problem was we–my writing partner and I—didn’t find the interviewees ourselves. We relied on the theatre to connect us with the people who should be interviewed. I’ll never let somebody else determine who I’m interviewing again.

The other time when there was some friction with the community was in the writing itself. I wanted to write about victims and perpetrators of violent crime and how you move on after that moment. Some members of the community wanted me to write the world that we envision and hope we live in someday, versus the world as we see it today. I understand that because the community was like, “We don’t need another play about all of the pain and suffering. Why don’t you write something that lifts us up?” My answer was, “I don’t know how to do that.” This project was many years ago. I think I am a different artist today. I think now I could have found a way to do both.

Michael: Also we can be lifted up if we’re able to reconcile our negative emotions. If we just shut that up, that doesn’t really solve anything, right?

KJ: Right. That’s the hope, but I’m an interloper. And they’re living with this story all the time., That’s something I’m really coming to terms with now, the responsibility of parachuting into a story and taking.

Michael: Do you feel like you’re combating that by having been in relationship with Cincinnati for nine years now? Do you still feel like in that situation the longitudinal nature of your work avoided that pitfall?

KJ: Absolutely. You have to get to know the story in a deep way. With the piece I was just talking about, I only knew that story in that community in a superficial, interloping way. For Cincinnati King or ReEntry, I spent so much time on those plays. Years and years. Now I’m pretty happy with the idea that my plays take so many years.

Michael: Yeah, I ended up writing a first draft of a documentary piece in about four months, but now I’m looking back on it and thinking that there are a lot of holes. There are a lot of people I didn’t talk to. For me to actually tell this story in a way that feels authentic, I need to spend more time and go back to these people. I was interviewing them about events that had happened a month prior, which is, I think, a good time to talk to people. But it’s also interesting to talk to them again with greater reflection. Looking back on this subject, the protests related to Breonna Taylor’s murder, and the continuing search for justice… The perspective surely has changed.

KJ: My favorite part of this kind of playmaking is going back because that builds your natural arc. You don’t have to force a narrative if you just go back to those people and hear where they’re at later.

Sometimes it is useful for documentary theatre to be a mirror of society, and sometimes it should be a bridge, and sometimes those purposes are at odds with one another.

Michael: I’ve been thinking a lot about what you said, in terms of false equivalencies. I’m also coupling that with what we’ve been talking about in terms of story ownership. So I think it is very white of me to be focused on telling the right story the right way and then to wash my hands and go away. I’m thinking more about who documentary theatre is for in terms of the audience and who it’s dedicated to. You’re talking about how Need Your Loveis for Mable. And I’m kind of wondering, like, who is my play for beyond myself?

KJ: You’re on a quest, personally.

Michael: Yeah.

KJ: That’s the right place to be.

Michael: But it is tricky to engage in a personal quest that very much involves the lives and stories of other people, recognizing that it can’t just be for me or about me. It has to actively partner and be in relationship with all these other people, which true of theatre in general.

KJ: Now I’ll ask you a couple questions. If you were to make a brochure on the ethics of representation in plays based on real people, real things, what are your bullet points on that brochure?

Michael: Acknowledge that we’re talking about three-dimensional, flesh and blood people, not caricatures or stereotypes. We can simultaneously honor someone while including their idiosyncrasies and the aspects of them that we would not want to bronze. Sometimes it is useful for documentary theatre to be a mirror of society, and sometimes it should be a bridge, and sometimes those purposes are at odds with one another. And it’s important to make a list of non-negotiables about how the story is told. If you’re telling the story of Little Willie John, it’s non-negotiable that he’s played by a Black man. That’s a key part of who he is and the time that he lives in the story. But then you have flexibility in your missing pieces, in the details. What would be in your brochure?

KJ: Very similar. The three-dimensional thing. You cannot go in with an agenda because then people become props for what you wanted to say. Have questions that you want to figure out answers to and things you need to figure out. You have to be ambivalent about it. Even if that grant is going to give you a whole lot of money to write a piece about something, you have to be personally, deeply, truly interested in it, and you have to have the time to invest in that community. Two last things. The audience needs to understand the rules of engagement: when is something actual, and when are you representing it fictionally? They have to know what’s true and what’s not true. Last, we have to always question the notion of documentary or investigative. All of the words we use to represent what we do suggest a certain level of verisimilitude. We always have to question how true that is. I am just really inspired about the way that documentary filmmakers have become much more adventurous than we are about how all these lives and experiences are represented.

Michael: What do you mean?

KJ: Bless theatre people, we love rules. We love following rules. But there’s a dourness to documentary plays, like it’s got to be one way. It can’t have imagination. I’m so hungry for ways we can make them more imaginative and playful. Imagination can–and should–be paired with transparency. There are plenty of ways to creatively let the audience know which parts are real and which are fiction.

“This piece, “Amplifiers and Takers: Approaches to Interview-Based Playmaking” by Michael DeWhatley and KJ Sanchez, was originally published on HowlRound Theatre Commons, on January 6, 2022.”

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.