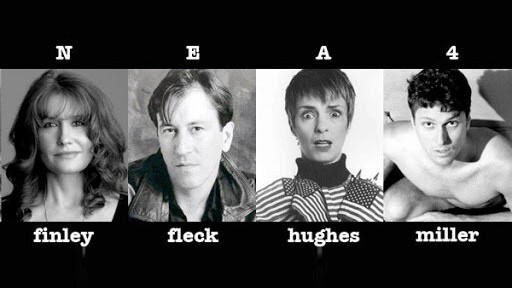

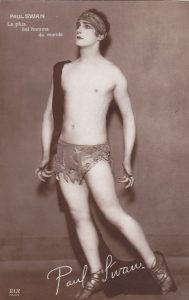

Janis and Richard Londraville are a husband-and-wife team of literary scholars. Together, they have published numerous biographies, including the 2006 book, The Most Beautiful Man in the World: Paul Swan, from Wilde to Warhol, the first comprehensive biography of Paul Swan’s life. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you get interested in Paul Swan?

Richard: I found out through Jeanne Foster (American poet and journalist, 1879 – 1970). I found out about her when I was doing research for my thesis on W.B. Yeats. I saw her quite a few times before I understood the depth of her connection with Paul.

Janis: She actually met him in 1917. Well, we know they knew each other in 1917. But she never really talked that much about him to Richard. And then she left these two photographs of her bust – you can see Paul’s signature on it – to Richard in her will. And Richard was saying, “Who’s Paul Swan? Why did she leave these things?” He loved Jeanne. He knew Jeanne very well and figured, “Well, if she left them to me, it must be important,” but he had a lot of other stuff going, didn’t you?

Richard: No.

Janis: Heh, so then I came along and my middle name is Swan. And I thought, “Gee, well this might be interesting,” because we were doing a lot of work together and I have a friend who was the director of the library at the Ringling Museum of Art at the time. And the two of us got cooking on it to find out who he was. And one thing led to another, and here we are today.

So, it’s kind of like Jeanne gave you the next project to do?

Janis: It was kinda mystical in a way. She had given these things to Richard for some reason and no one knew, so we just got curious and it was really fortunate. It took a lot of years for it to be the right time for a Paul Swan biography. Gay studies had to come about a little bit, and the Whitney started saving Warhol’s films, and everything just kinda clicked. There was a PBS movie on Jeanne Foster’s life just before we did her biography. Everything just sort of mystically came together.

Richard: The other thing that’s important is that she knew so many people, that a lot of people would come to see her. Of course, at that time, Paul Swan wasn’t known as much anymore, but they would see her about Joyce and Yates. I particularly liked talking to her, that’s why some of this stuff came out.

Janis: And her letters to Paul, or, Paul’s letters to her, I forget which way it goes, are at the New York Public Library. Around the early sixties… like ’62 or ’63, you know, he asked her to write his biography. But, Jeannie was eighty-two at the time and she was wise enough to say no. He did write one. It was really… bad. There were great glimpses in it, but he didn’t know how to tell the story of himself. Few of us do. This is in his autobiography – it’s Paul talking about himself, and this is kind of funny: “He recorded stories of his conquests… because they made him look powerful… Once, when Fred Bates called him a gigolo, he reminded him that he did not have sexual intercourse with these admirers. Fred, who often acted as Paul’s conscience during the years they were together in Europe, which was about ten years, added that, ‘Other men are not as clever as you. You give the ladies what they ought to have. Real gigolos give them what they want. With you they talk of Christ, Greek gods, and lots of saints. They become ashamed of their desires.’”

What do you know about his dancing in Europe? How good was he?

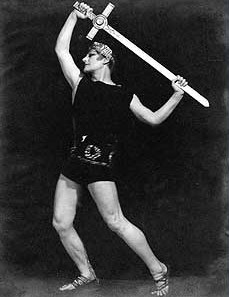

Janis: When he was young, he had a lot of attention and he had a fan club. But how good was he? Well, you saw the film. It was that kind of aesthetic dancing that Isadora Duncan did.

Richard: If you know Lily Fuller and her troupe of dancers, that’s representative of what was happening at the time. I think most of those shows would look kind of forced to us now. One of the difficulties he had, for example, working with Cecil B. DeMille in The Ten Commandments, was that he was in charge of some of the dances there and he and DeMille had a real falling out. He wasn’t ready to compromise.

How big was he in America?

Janis: When he was younger, he did draw some crowds early on. I think that was around the Chicago area and there’s some article that says he drew more people than a Russian ballet that was coming. I think his type of dance was more suited to a European audience. When he came back from Paris he was a nobody.

And he had to abandon all his artwork in Paris. No one knows where it is.

Janis: Once in a while, pieces turn up. At least with the biography being out there, somebody googles Paul Swan and they’ll either get our guy or a current Irish artist named Paul Swan. We were contacted by a cardiologist in Ohio a bunch of years ago. He had an incredible life-size painting of Ophelia on burlap that Paul had done in Greece in the early part of the 20th century. Somebody saw it in Virginia, and then this cardiologist found it in an antique store in Kentucky. He bought it, and he spent a ton of money having it restored properly. I’m glad so many of them are saved now. One of his family members, not a family member by direct blood, but, the wife of one of his relatives had a painting of his and she decided to cut it up and decoupage it. So, this wonderful Paul Swan painting, she cut it up into pieces and she decided to make a decoupage.

Why?!

Janis: Why not? I mean nobody knew who he was at the time. You know, he was just an eccentric man. Dallas Jr. [Paul’s nephew] told us these stories about how he would go walking down the streets of New York City, and everyone wanted to know who this old man was, like he must be some retired movie star.

Richard: There was a Hollywood Reporter review on our book that goes through a great deal of detail about how Swan is important to people of his time, because he was able to go through life relatively unscathed at a time when it’s hard for us to even think of it now. What he was doing would make him liable to be in prison at any given time. He was able to walk through the world much more freely than most homosexuals would at the time. He was very lucky to have a wife that he could fall back on, and if someone ever said, “You know, are you homosexual?” he’d say, “Are you serious? I’m married and I have two children.”

Janis: He always talked about Helen. That was just a beautiful, loving friendship. She was very supportive of everything. There are very few examples of a gay person moving through that much of life in that part of the 20th century. As he grew up, he found more and more who he was as he went through this whole century. And I hope he was able to find a place of peace.

How did the idea of the salon performances come to Paul? Was that something people normally did at that time?

Janis: It wasn’t unusual for those old artists who lived in Carnegie Hall, or, even at the Van Dyke, after they got kicked out of Carnegie Hall, to try to hang onto their art. But I think with Paul, from the time he was very young, if you put him in a room, he started to perform. He was always a performer, and he fed off it. He had some very interesting people come to see him, and they saw him as a curiosity when he was older, but they still came. I think it was not unusual for the Carnegie group. There was a number of artists there. Charles Avery Aiken, who was quite an artist of note, ended up poor. Paul actually borrowed money from his brother, Dallas Sr., which he was always doing, but he helped to support Charles Avery Aiken. So, he was a generous man, but he was sometimes generous with other people’s money.

Richard: Yeah, the relationship with Dallas is an interesting one, because Dallas would buy his paintings to support him. And then Paul would go to visit Dallas, assert that he hadn’t been paid enough for a particular painting, and he would try to take it back.

Janis: And the irony of it is, because of Dallas Sr., some of Paul Swan’s paintings exist that probably wouldn’t exist, even though there was a lot of angst between the brothers.

Do you know if Paul ever saw the Warhol film? What was he expecting going in?

Janis: He never saw it. When Paul finally got the check from Warhol, he had become senile. He didn’t remember the film and didn’t know what the check was for. I don’t have a specific answer [about Warhol], but to make icons out of trash. You know, like the Campbell’s soup can. And my feeling is, it was basically the same thing with Paul. He put that camera lens on him, Paul said, “You’re going to edit this out, right?” and, of course, Andy was never going to do that. Paul didn’t know what to say. In the film, Andy says, “Just do something or other. Read one of your poems.” I have a friend who knew Warhol very well. She said, that’s just what he did, he found these interesting pieces of trash – I don’t want to call Paul Swan a piece of trash, but, you know what I mean – and make them into art. Paul Swan the artist became the art.

Anything else?

Janis: This is kind of a private thing, but it made me feel so good. Dallas Jr. flew me up in 2006, just before the book came out, to be at a big Swan family reunion, and one of the grandnieces – she was a lesbian – she came over to me and we sat and talked about Paul. And she said, “You know, for the first time, knowing about Uncle Paul, I feel like I’m a part of this family.” And she didn’t mean that anybody was pushing her away, it was just… her place in the universe of it all. And it made me feel so good that he had done that for her. Would you also tell Claire that we applaud her? There are so many people who are attached to Paul Swan in one way or another, and we’re so happy that this play is being done. Appreciate it far and wide.