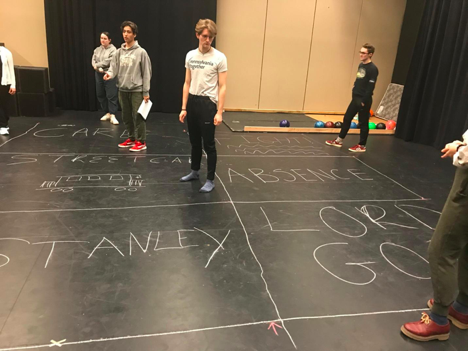

With six weeks of rehearsal in the balance, in March an ensemble of actors and production team members at Wesleyan University took a break from moving out of their dorm rooms to discuss the future of their show amid a rapidly developing pandemic.

“We were at that prime moment in rehearsal where we were tipping over into the show blooming around us,” said director Katie Pearl. “We were so invested in it.”

Ten student actors, led by Pearl, an Assistant Professor of Theater, began rehearsals in January as part of a theatrical experiment: could The Method Gun, an inventive and challenging piece of devised theater, have a second life? The play, created by Kirk Lynn and the Rude Mechs, an Austin-based theater collective, had never been performed by another theater company. In the face of a global health crisis, without an on-the-fly pivot, all of the Wesleyan team’s work stood to be lost.

Devised theater is a method of building plays from games, exercises, and rehearsal improvisations, rather than starting from a written script. Because this work is created collectively, devised pieces are often directly linked to the performers who originated the work, making these shows more challenging to revive than typical plays.

“All of these incredible pieces just stop when the companies stop doing them,” said Pearl. “So the question was: ‘What if, to a certain degree, we peeled the play back to the original prompts and a new company devised around those prompts?’”

[The May 1 and 2 performances of The Method Gun are available to view for free at the Wesleyan University Theater Department’s YouTube channel.]

In the original production, The Method Gun followed the Rude Mechs’ investigation into the Stella Burden Company, a (fictional) theater company with an intense commitment to Method acting. After Burden abandoned her ensemble, the actors she left behind embarked on a nine-year rehearsal process of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire without any of the main characters. The show alternated between the Rude Mechs’ present-day presentations of their research and re-enactments of Burden’s Company’s rehearsals, culminating in an epic ten-minute performance of Streetcar while swinging lights swooped across the stage.

Over nearly 100 hours of rehearsal, Pearl and her ensemble created a new vision of The Method Gun, reconceiving the Rude Mechs’ characters as Wesleyan student actors and swapping the obstacle of bowling balls rolling down a raked stage at the climax for the Mechs’ swinging lights.

The team’s plans, however, soon encountered a major hurdle. As the University headed into spring break, colleges nationwide began closing their doors in response to the coronavirus pandemic. On March 11, in the middle of break, Wesleyan President Michael Roth suspended in-person classes for the rest of the semester. So instead of coming back to resume classes, students returned to campus to move out of their dorm rooms. It was in the middle of those quickly shifting circumstances that The Method Gun team faced a day of reckoning for their show.

The meeting was emotional. Those present in the Theater Department lounge sat a socially-distanced six feet apart from one another, while others joined from their homes on Zoom. “I remember just wearing this hoodie and sinking into this hoodie and wanting not to be seen by anyone,” said actor Max Halperin, class of 2020. Before spring break, the actors would cuddle and lay on the floor together. Suddenly, “we couldn’t hug goodbye.”

“Artists are always expected to be exceptional in the worst of times,” said Esme Ng, class of 2022. “I said this to the group, ‘I’m really tired of that.’ We should be allowed to mourn and not have to jump back into this productive mindset.” For Ng, an Asian American actor from Staten Island, “one of the things that was always on my mind was the rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans. I broke down crying in front of my friends saying, ‘this is a really stressful time.’”

Many options were on the table. In the eyes of Pearl and the Theater Department, the students had rehearsed enough hours to conclude the project and receive full course credit for their work. Public safety permitting, the team could return to the show in the fall and invite the sole graduating senior in the cast back as a guest artist. Or, they could experiment with presenting their work online.

Opinions varied as to what to do. Actor Elijah Comas, class of 2022, was reluctant at first to continue. “To me,” he said, “it felt like we were dragging the corpse of this play through the mud.” On the other hand, Miguel Perez-Glassner, an actor from the class of 2021, “was very desperate to keep going in any way.”

Walking away would mean saying goodbye to hard work and a tight-knit community. Bringing the production back in the fall could limit future students’ opportunities to partake in a mainstage Theater Department production at Wesleyan. An online version might turn into a pale imitation of what the team had worked so hard to build.

Ultimately, Pearl said, “Okay. We don’t know what it’s going to be and we’re not sure how we feel about it. But I think what we need to do is come together and start by reading through the play again. We have to see what the play is.” The team adjourned for a week and agreed to explore bringing The Method Gun online.

For five weeks and eighty-plus-hours, they rehearsed and teched on Zoom, figuring out along the way how to unlock the artistic potential of a platform designed for conference calls in advance of livestreamed performances on May 1 and 2.

At first, it was challenging to maintain focus online. “Rehearsing for three hours over Zoom feels like a year,” said Halperin. Juggling time zones was also difficult: members of the cast lived everywhere from Singapore and Macedonia to New Hampshire.

But as time went on, excitement for rehearsals grew. Spending time together meant the team could stay connected to one another and had the space to process their feelings. “Going to rehearsal became a way to sit in the sadness of what’s happening but also continue to produce something exciting,” said stage manager Betsy Zaubler, class of 2021. The challenge of making work on a digital platform was invigorating. “Everybody is working from a blank slate,” said actor Liz Woolford, class of 2021. “It doesn’t matter if you’re Yale MFA folks, you have no idea how Zoom works as much as we have no idea how Zoom works. So it’s a fascinating time to be trying to put up theater.”

Creating this piece within an educational context gave Pearl the permission to experiment and the drive to persevere. “As a director, this is making me realize more and more what a deep value it is to create a community of my actors and my ensemble,” she said. “Now it’s right up front. That is what I’m doing, and that matters to me. And the way I make community is by making something together.”

I think we were in the 1% of most engaged college students right now.

Max Halperin, class of 2020

For Halperin, that commitment to community paid off. “I think we are in the 1% of most engaged college students right now in this process because no one’s actually on their phone and no one’s doing anything else. We’re all constantly engaged and acting and working through it.”

When Pearl first approached Lynn and the Rude Mechs to ask if they would let her revisit The Method Gun, she received permission to adapt the play as she saw fit to her Wesleyan community. That carte blanche proved essential to fit the play to Zoom. The ensemble rewrote the script extensively, incorporating isolation as part of the Stella Burden Company’s acting technique to make sense of why the show would be performed on Zoom. A prologue was added to prepare audiences to experience the retooled show online. A scene that originally involved the Stella Burden Company engaging in “Kissing Practice” with one another was reimagined as a scene where isolated performers kissed the nearest objects they had at hand.

Slowly, the process of making The Method Gun began to parallel the story of the company they were portraying. “In both situations there was this keystone that we took for granted. For them, it was Stella Burden,” said Perez-Glassner. “We took for granted that we were physically together in the same place, that we were going to perform on a stage together. When that goes away suddenly, and you don’t know what to do, you have to come together and figure out on the spot how to move forward.”

Even Kissing Practice felt relevant to their new realities. “For the students in the cast, one thing that’s very real for them is they can’t have sex with their people,” said Pearl. “Kissing practice became a way for them to try to, in a tongue-in-cheek way, feel sexuality and intimacy using objects in their room.”

One discovery was crucial: by choosing the order in which actors entered into a Zoom meeting, Pearl could control the actors’ positions on the screen. This allowed for creative scene compositions, with key characters being placed at the center of the screen or far away from the action, depending on what a scene called for. In some scenes, actors “passed” objects from their box on Zoom to their neighbors’ boxes, aided by duplicate props that had been shipped to the actors’ homes.

Many findings were exciting. For scene transitions, actors would exit the meeting while a title card filled the screen. Each actor was shipped a green screen that allowed for creative backgrounds at a few pivotal moments. Giving each performer a real plant added scenic cohesion between their individual Zoom frames. Adjusting camera angles allowed for dramatic point of view shots and clear differentiation between scenes of the cast members as themselves versus scenes portraying members of Burden’s company. PowerPoint and FaceTime added additional flavors to the show. Dramaturgs even built a website that delved into the history of the Stella Burden Company for interested audience members.

The cast had personalized lighting and scenic design meetings for their stages: childhood bedrooms, dining rooms, and living rooms that quickly grew littered with spike tape and prop tables. “I have banned all members of my family from my room so they don’t accidentally move things,” said Woolford.

“I have banned all members of my family from my room so they don’t accidentally move things.”

Liz Woolford, Class of 2021

Not all technical experiments were successful. The actors were shipped sheets of gel filters to adjust the color of their lighting, only to be foiled by an actor’s color-correcting camera. During the final dress rehearsal, the stage manager got kicked out of the conference call in which she called cues, pausing the show. Late in the rehearsal process, the team realized that, on Zoom, every user’s screen has a unique arrangement of speakers, potentially ruining weeks of blocking. But the team soon discovered software called OBS to broadcast Pearl’s screen and ensure that viewers saw what she saw. It also allowed for the kind of color correction the team aimed for with gels.

After months of preparation, it was finally showtime. In live chat next to the YouTube broadcast, viewers said hello to friends from around the country and responded enthusiastically to the performances. At one point during the closing performance, Lynn, the original playwright, asked in the chat if the actors were using real beer in violation of the performance agreement with the Rude Mechs. (Answer from the Assistant Director: no—the set designer shipped custom beer labels to the students to use on soda cans.)

Minor glitches occurred: occasionally, the internet slowed down; one performer’s computer broke midway through the first performance, and an assistant director, serving as a swing in case of internet lags, briefly stepped into his role.

The overall experience, however, was thrillingly live. Actors livestreamed monologues and played instruments, burned letters, danced erratically and dressed in tiger costumes. In one particularly moving moment, the actors watched footage of themselves rehearsing before the pandemic.

The Rude Mechs maintained a text thread during the show, “saying how much we were honored by the students and loved what they were doing,” Lynn said. “In some ways the greater the obstacle, the greater the beauty of it. Because they had to do it in a way that was so difficult, it might be the most beautiful production of Method Gun.”

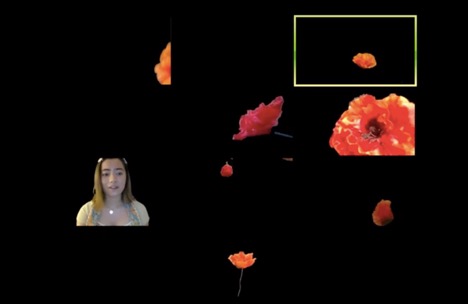

Stills from the final Streetcar performance.

Of course, there was still the question of what the Streetcar performance would look like online. “Because a large part of the audience knew how it ended, it was definitely building toward the final production and, ‘how will they pull this off in this medium?’” Lynn said. While reading stage directions against pitch-black backdrops, the actors performed a haunting dream ballet that leaned on audience members’ imaginations, surreally depicting Streetcar with images of flowers, puppets, and hands suspended in space while also acknowledging the bowling balls the performers had been forced to leave behind.

To close the show, just like in the original Method Gun,the ensemble engaged in a final Burden exercise: two minutes of “Crying Practice,” while the names audience members submitted at the top of the play of important mentors were projected on screen. The experiment completed, the actors’ faces slowly turned to grins.

The team’s pride in what they had accomplished was obvious. “Three weeks ago, if you told me that the rest of the theater I was going to make was going to look more like this than what I’d previously made, I’m not sure that I would still do it,” said Comas. “Now I feel less sure.”

“I hope one day people write a play about us,” Perez-Glassner said.

Author

-

Daniel Krane is a Brooklyn-based director, playwright, and arts journalist. He was the Civilians' Editorial and Social Media Intern for the 2019-2020 season. In addition to his work at the Civilians, he served as the Artistic Director at Princeton Summer Theater for two critically-acclaimed seasons, and has worked for the Public Theater's Public Works program and the Brooklyn Arts Exchange. His writing has been featured in American Theatre Magazine, Exeunt NYC, and Extended Play. He received his B.A. from Princeton University in 2018, where he studied Portuguese and Theater. DanielKrane.com

View all posts