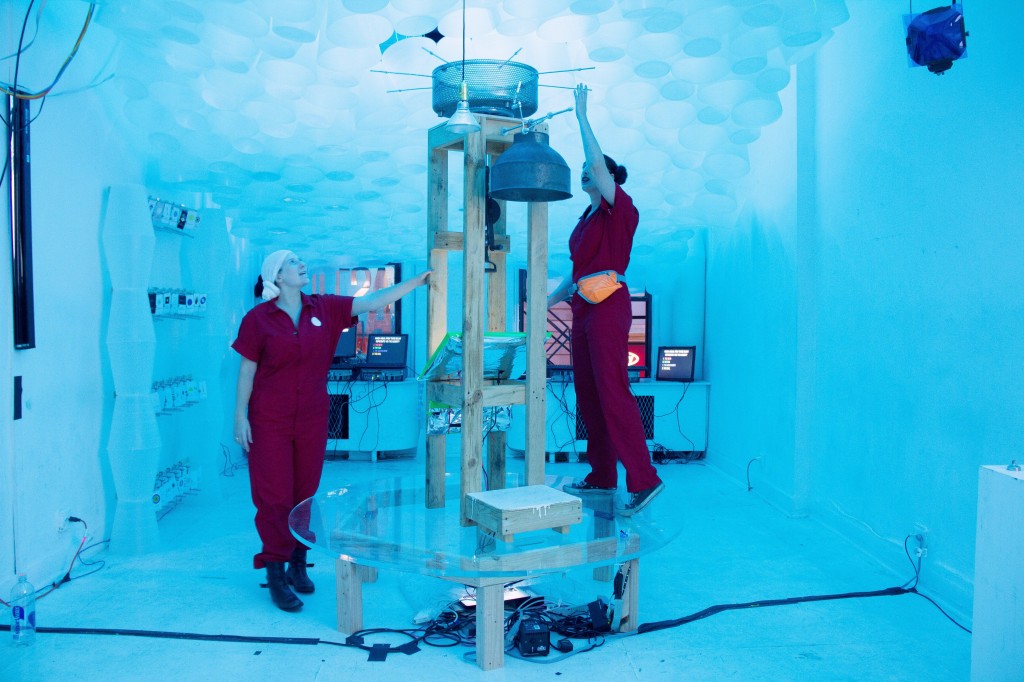

In his musical “The Universe is a Small Hat,” writer/composer César Alvarez invites audiences to build a society on a techno-utopian space colony.

Ian Daniel, Editor of Extended Play, attended César Alvarez’s new participatory musical set in outer space, “The Universe is a Small Hat,” at Babycastles Gallery in NYC. The show is set in the year 2114, when artificial intelligence, humanoid robots and Martian colonies are all real things. In this futuristic world, a group of humans leaves Earth to establish an entirely new society in space. The audience plays the colonists, and their choices shape the development of the new world.

César developed this project as part of the Civilians R&D group in 2013, during which time he was studying how to make a new and truly immersive piece of theater. He ultimately chose to use the form of a game, so that audience members could, as he says, “notice what role they might play within a complete redesign of reality.”

Ian and César spoke about the current state of participatory theater and how César’s piece is pushing audiences to get involved in boundary pushing ways.

IAN DANIEL: What is happening with this trend or sudden interest in participatory theater? As it becomes more common, how do theater makers go about creating an immersive piece that is meaningful and unique?

CÈSAR ALVAREZ: And not just as the apotheosis of consumer capitalism? Well, you’re right – there is this possibility with immersive theater that it’s just become this orgy of production. There’s a way in which this could lead to a failure of the imagination, but I actually think there is something really contemporary about the need people have to stand up. I think it has to do with the internet at large and video games. Pretty much anyone who was a kid during the advent of the internet has learned how to tell themselves stories and investigate the world through choice and through open-ended content stream. So the form of sitting down at a theater, facing in one direction watching a story play out — while I think that will never go away — I think there is a very big wave of interest in, “How do we tell stories that allow for the kind of choice-making that we experience in our day-to-day lives and in our social networks?”

Thirty years ago, when I wanted to learn about tornados, I’d go to the encyclopedia. And if the encyclopedia didn’t have it, I’d go to the library and look for a better source. There’s a sort of directional stream as to how you learn something. And now we learn to think non-linearly and it’s really exciting — there’s a story but there’s no one angle to explain the story, and I think what we’re trying to do is find a theatrical language that allows for an exploration of humanity with a different level of agency. We’re doing what theater has always done. We’re just using new mechanics and a new kind of mental architecture created by the internet video games and social networks.

IAN: Did you see the Ted talk about gaming by the game designer Jane McGonigal? Her point was essentially this: people spend 3 billion hours a week playing video games, and studies show that we are much happier working than relaxing. Given those facts, why not make gaming more productive by applying it real world problems? Games can be a powerful platform for change.

I see how the type of theater you’re making can do that as well. It pushes us to experience a heightened version of ourselves…looking at ourselves differently in a play space can inspire our imaginations for what’s possible in real-life space. When the experience of your piece was all over, I was sort of lost or discombobulated. I went out into the real world looking and hoping for more random, playful interactions. Your piece certainly made me want to push my real world interactions a step further, a recognition that it would be nice to play around with each other a bit more in life. Is that key to the interest in this type of work?

CÈSAR: People are desperate to play with one another. And I think in our culture, human beings are dying to play for their entire lives. But the rigidities of our culture as it emerged out of the dark ages created a sense of play as something for children. At a certain point, you have to stop playing. It’s also a societal survival mechanism. But we are definitely at a point now when we are realizing that it’s actually important that our adult minds not become rigid.

“Let’s come up with sophisticated ways to create safe spaces for adults to play with identity and societal roles. Ultimately that is what art is for: to help people be more human.”

The act of play is a sort of circulation of identity. It allows who you are to bubble and transform, and I think the idea of play is so essential to what we are trying to create in this piece. And again, it’s so essential to theater. The origins of theater are ritual and group collective play, and only recently in history did it become a specialized thing that only specific people would do and others would watch. All over history and our culture, we find ways to continue to play. What we are trying to do is take that to the next level. Let’s come up with sophisticated ways to create safe spaces for adults to play with identity and societal roles. Ultimately that is what art is for: to help people be more human.

In game design and video games in general, there has been this real struggle. Are games art? Can games be art? I think it’s really funny to look at the world of video games, because it’s very similar to the world of musical theater. The musical theater world is highly curated by economic interests, because they are so expensive to produce. Musicals are so expensive to produce that the people who have the money to produce them end up curating them heavily. Video games are the same way. They are very hard to produce, so we have corporations trying to create a sure-fire hit. What’s resulted is a limited exploration of a form, and… my interest is to take these fascinating forms that have very strong cultural reputations: video games for being violent and geared toward men — young men — and musicals for being cheesy and geared toward kids and people who like sappy love stories. I feel like taking these two, video games and musical theater, and trying to create a live-action social experiment with them is really fun. And what I’ve noticed, it feels like a thing people will want to do. It feels like a form that could be an option for social interaction.

IAN: I went to a benefit party for Rhizome at the New Museum where artist Ed Fornieles, who designed the party, asked guests to take on heightened personae inspired by film characters and pop culture narratives, from Patrick Bateman to Woody Allen, “Sex and the City” to “Girls.”

He called guests ahead of time and gave everyone their persona. I got “sociopath,” and it was my duty to define that character beforehand. That simple task made it easier for people to interact and let loose. It created a freer, wilder atmosphere, so much so that by the end, we were all breaking the furniture and lying on top of one another in an orgy of sorts. In what ways are you preparing your audience for the experience, and how is that important to the piece?

CÈSAR: We changed it a lot from when you saw it. The last show we had a really different set up. We gave people more information ahead of time, and the result was this really deep character work that the audience did. It was way more immersive in that way. People took on all these backstories, characters and narratives in a way we had never seen before. One thing that was really interesting I read in game design books, you can’t design play. You can only design a system. You can’t actually rehearse how something is going to play, how your system will get used. We’ve been continually ratcheting up the system to see how people are playing. When our piece fails and collapses and dies — when people start poking fun at it or go outside of it or feel embarrassed — that’s a failure of game design. When the piece is working really well, players are in an unselfconscious mode of total fiction where they are able to experience a whole other life. That’s the ultimate idea. And when they go back to their own life, they get to superimpose that other way of being of who they actually are. And out of that rub, there is transformation.

“How do you use theater as a way to sort of crack people’s brains open. How do you get them to practice making choices in complicated systems?”

Even if you are making someone play a sociopath, you are building the muscles of their emotional mind. I think that is really exciting as an artist. It’s about the most exciting thing I’ve ever done. I consider myself a Brechtian. He talked a lot about helping people practice the act of liberation, and I think that’s what we are aiming for, what he was thinking about, which was, “How do you use theater as a way to sort of crack people’s brains open. How do you get them to practice making choices in complicated systems?”

IAN: Some of the participants appeared so fully immersed in the game and committed to the world that I thought they were your actors you had planted in the piece. But I talked to one of them after and this guy said, “No, I’m just a nerd, and I get really into it this. I work at Google.”

CÈSAR: It happens every single night of the show. Every time, there are people who come in with incredible ideas and narratives, and we’re trying to make a piece that can absorb all of that. At the end, we’re all these actors sitting back watching all these people perform our piece. And we didn’t train them or rehearse them. We just created a system of play they were able to navigate. You feel like you’re surfing a wave in that moment. We’re using archetypal language that people are already bringing a lot of knowledge about, based on their reading of science fiction, based on their interest in technology, based on their engagement with political philosophies. People are bringing all this into the piece, and then it becomes part of the story.

IAN: The more emotionally moving moments for me were the times when you elucidated the fictional world of the piece through song. I wanted to ask you about the importance of using music in the theatrical environment and the fictional realm. Were you also using music as a bonding ritual?

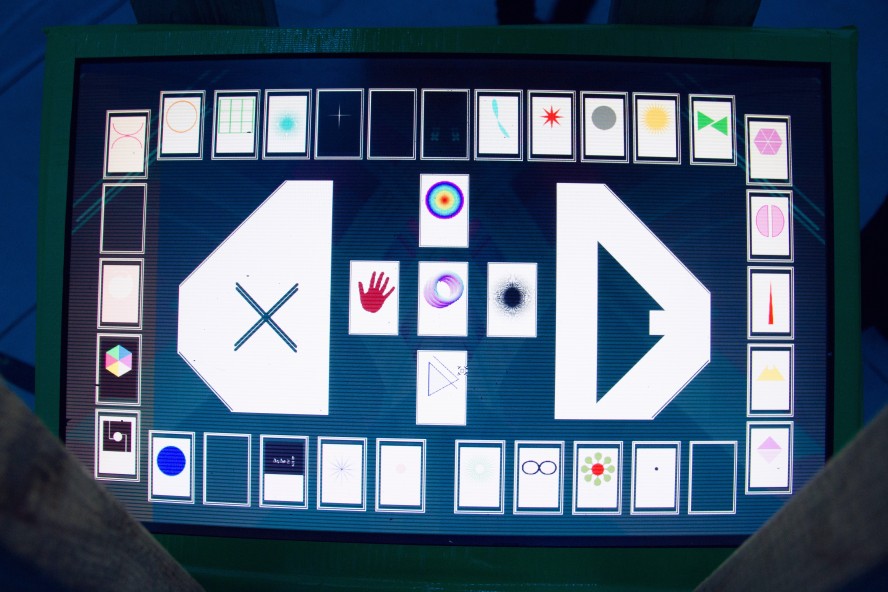

CÈSAR: One of the things I noticed when I first started researching video games is that the form of most conventional first person shooter video games is “game play, cut scene, game play, cut scene,” which totally mirrors for me the form of a musical, which is “song, scene, song, scene.” I thought there was something really connected there. Video games and musicals both operate on two completely unnaturalistic planes of fiction, each one serving its own different function in the narrative. And the line between them is totally fantastical, and you just sort of accept it as part of your engagement with the form. I wanted to use music as the cut scene. So the form of my piece is “game play, song, game play, song.” And what the songs do is they actually give you a break from having to figure out what to do. They give you information about the world. And they let you make new decisions about how you want to play and plan ahead. And they let you more passively strategize, and it’s kind of what you do in video games. It’s a different kind of engagement, but it’s also like the songs in musicals. They let you kind of marinate in the emotional landscape of the story. And they kind of alleviate you from things. But sometimes they push things forward… A lot of times in musicals, it’s really tricky to figure out how the song starts, and I’ve found the songs help me so much getting in and out of the game play. I turned this musical into a game to solve a problem.

Originally I wrote a musical… about two astronauts bored to the point of insanity. And I was trying to explore the human inadequacy to actually deal with what our universe is made of and how it’s so odd that we all are from space and floating in space. But if we actually go out into it, it’s incredibly harsh on who we are and hard to live and be. And that was the initial exploration. When I made it into a normal book musical, I wasn’t satisfied with it. It felt quaint, and I wanted people to feel the feeling viscerally, which is why I decided to create a world people had to step into and engage with.

IAN: How did you go about figuring out how to make this into a game?

CÈSAR: I started picking apart games in the ways that I’ve always picked apart music. And then I started figuring out that there’s actually a lot of information already available about how you create big multiplayer experiences. I ended up going to Scandinavia to research Nordic Larp, which is a progressive art scene where people are creating social experiments and telling all kinds of different stories.

IAN: What is Nordic Larp?

CÈSAR: Scandinavian progressive/experimental live action role play. It’s a 20-year-old tradition of creating these very complicated systems and stories. It’s an art scene, and there’s all this information about how you create player experiences and tell stories over a period of time. I realized I could just choose a lot of what has already been discovered about creating immersive narrative and incorporating that into a conversation about immersive theater in New York. In New York, there’s been a lot of headway made about how you make an immersive world, and so what I’m trying to do is say, “OK, let’s create the immersive world, but when you walk into the world, you’re going to be part of a very sophisticated system of play that can allow you to actually experience the consequences of your decisions.”

I’m trying to allow people to experience the consequences of their play, rather than having just an ambulatory experience where they are watching something unfold, which is also exciting. But I was trying to have a situation… where there would be consequences, which is how gaming works — which is how sports work, right? If you’re playing soccer, you experience the consequences of the way you play. That’s why it’s so immersive, and that’s why no soccer game is ever the same. It’s endlessly fascinating for people to play sophisticated games.

IAN: Right, something like “Sleep No More” is pitched as an immersive experience, but the audience doesn’t feel real consequences of play. They are not a character in the piece. So it’s a question of how “immersive” is defined. Is it about being a player that can activate a world or being an observer in a curated space?

CÈSAR: Have you ever played the game “Myst,” one of the earliest immersive video games? It’s from the 90’s. It’s a game where all you do is just walk around. At the time it was revolutionary, because it was a whole world you could explore. There were a few little puzzles in it, but why it was so exciting was because it was a whole digital world they had created. It was a foreshadow for games like “Bioshock,” which are these really radical and immersive worlds that also had very sophisticated gameplay. And I think “Sleep No More” is revolutionary in the way that “Myst” was revolutionary, in that it sort of set the bar for what is possible in terms of creating a world. And now I think everybody is starting to say, “OK, we know we can create these worlds. How can we start designing the play that happens inside?” We are at the very beginning of the evolution of a form. I’ve talked about “Sleep No More” to a lot of gamers who were frustrated, because they want to play and have an impact in the way that a video game or larp would allow. It’s the beginning. It sort of threw down the gauntlet of what was possible.

Photos courtesy Joe Perez for Babycastles and Jesse Untracht-Oakner

Authors

-

-

César Alvarez is a Drama Desk-nominated composer, lyricist, performer and writer. His Civil War sci-fi musical "FUTURITY" world premiered at American Repertory Theater in 2012 and was a co-commission of Walker Art Center. César's band, The Lisps, has released 4 albums and played hundreds of shows around the country since 2005. César is co-founder and resident composer of the LA-based dance theater company Contra-Tiempo. He has presented work at Lincoln Center, MASS MoCA, the Stone, Roulette, Dixon Place, the Tank, Joe’s Pub, HERE, La MaMa, Dance New Amsterdam, Ars Nova, Walker Art Center, ASU Gammage, Ford Amphitheater, RedCat, and CounterPulse, among others. César was a member of the Civilians' R&D Group for 2012-13, a visiting artist in the Sarah Lawrence College Theater Program and a Visiting Lecturer on Dramatics at Harvard University. He writes about theater, music and science at www.musicisfreenow.org.

View all posts