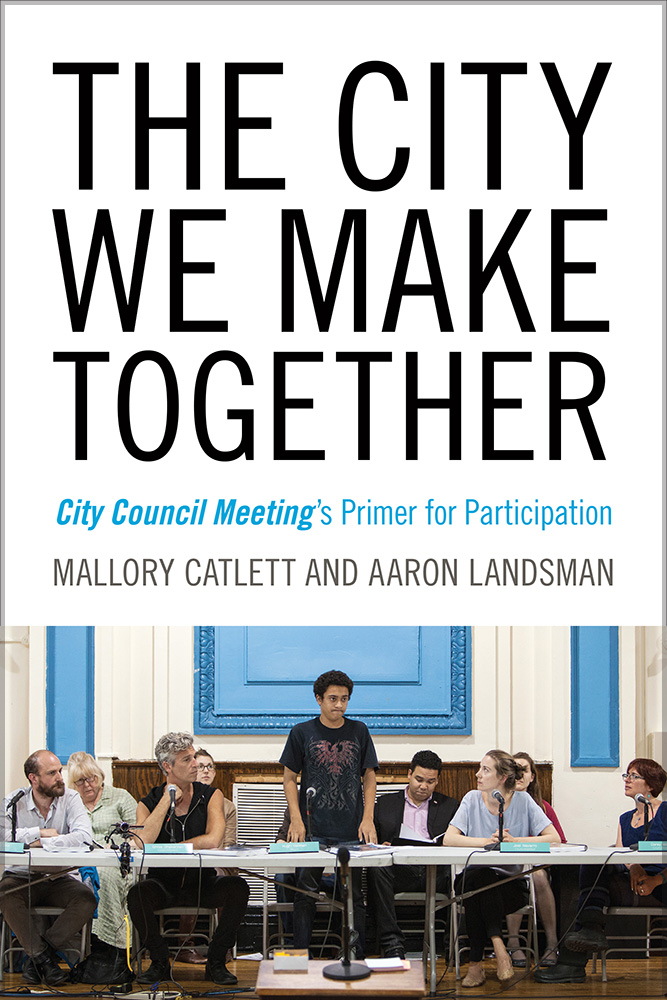

The City We Make Together: City Council Meeting’s Primer for Participation, is Aaron and director Mallory Catlett’s account of their engagement with city councilors and citizens, working together to understand how, when, and why democracy works. Aaron and Mallory created the show, City Council Meeting, so residents could participate in an artistic version of the civic ritual which is a municipal government meeting.

In Meeting the Moment: Socially Engaged Performance, 1965-2020, by Those Who Lived It, Jan and cultural activist Rad Pereira weave stories from over 75 interviews and informal exchanges, adding their own reflections. The book includes a chapter on theater makers collaborating with municipal government agencies and other civic partners to address local challenges and issues.

What follows are excerpts from Aaron and Jan’s conversation.

Aaron Landsman: I like being two artists conversing together.

Jan Cohen-Cruz: Well, I’m not exactly an artist but my practice is related; participatory research is a large part of my writing about performance and I still teach, too. How do you describe yourself?

Aaron: I’m a theater maker, teacher, writer, instigator…

Jan: Neat. We both have identities that situate our art selves in a cluster of other activities.

Non-exceptionalism: artists are humans responding to the world around them

Aaron: Yes. It’s been interesting to me as an Abrons Arts Center Artist In Residence to be part of Henry Street Settlement, which is focused on service delivery in several areas – literacy, food, shelter, culture, housing and work. During the pandemic, Abrons repurposed the main stage theater into a giant staging area for food delivery and served a thousand bags of groceries a week. They kept the production staff employed at a time when theaters were dark; since Henry Street already did food delivery and the demand for it went up during the pandemic, the turn served a lot of needs at once.

Jan: The theater literally built a giant fridge and participated in food delivery?

Aaron: Yeah. The first thing was to put Abrons staff to work in the food pantry because lots of people in the neighborhood needed food who hadn’t before, and other artists volunteered to deliver. Tylor Diaz, who’s a composer, and part of Perfect City–

Jan: Which is…?

Aaron: That’s a project I instigated at Abrons that includes performances, mapping exercises about belonging and avoidance, roundtable discussions, writing, and research on street harassment and gentrification. Tylor became manager of the food pantry when the pandemic hit, at another location. Then they needed that space back. So the tech staff literally built a fridge and coordinated the delivery. It was really deep. It’s rare that the arts are such a pillar of a large non-profit like that.

But Henry Street is still really focused on serving the needs of people, and those needs are often brought about by systemic inequities. If the world’s problems went away, there wouldn’t be a need for a Henry Street — that’s the world that many of us as artists want to think about. At the same time we’re so far from it. So of course it’s good that there’s a Henry Street.

Jan: What you describe busts the idea of exceptionalism and embeds artists in life. It’s part of the reason I like the civic turn so much, with artists and municipal staffers collaborating. There’s an uptick in artists who want to work with particular populations collaborating with municipal agencies that serve those groups. The Mayor’s office of Immigrant Affairs here in New York City, for example, brought in Tanya Bruguera to devise a project to instill more trust between the agency and NYC immigrants. Artists develop trust differently than people who spend most of their time working at desk jobs.

Aaron: Your chapter on the civic turn impacted how we’re thinking about the curriculum that we want to make out of our city council meeting project and book. I think, in Meeting the Moment, it was Rick Lowe talking about it– If you start making your work on your terms, and it’s firm enough, then you can go to a municipality and be, “This is what it is; you can hop on board.” That feels key to me.

Outcomes and Discovery

Jan: Rad and I encountered a number of factors that impacted municipal-artist collaborations. For one, city agencies often feel an enormous burden to prove that they’re using taxpayer money well. That is a challenging starting point for an artist who’s trying to collaborate. Some artists that Rad and I spoke with negotiated it better than others.

Another factor is how well the city liaison understands art. The tension we heard the most is that artists are about discovery and government staffers need to know outcomes up front. So in a way, these are impossible partnerships. But in fact, so many artists love when there are outcomes they can go for with particular projects, and so many people who work for cities love when things open up, and they can find what they haven’t found — or even looked for — before.

Aaron: “We know you need outcomes. We also need discovery.”

Jan: Rad was part of the Lost Collective, a little theater group working with the Administration of Children and Family Services in New York City. They were working with LGBTQ youth in group homes. There had been a number of scandals where children in foster care had been abused, so the agency couldn’t take any chances at all. They were under enormous pressure. I was meant to write about that project. I was talking to people from the city about something that Rad said, that I found so lovely; which is that, in a way, the artists were like aunties and uncles that the kids didn’t have, because at least two of the four company members are queer and very open about that. That mattered a whole lot to those kids, most of whom had been thrown out of their homes largely because of their sexual identities. And the city staffer said to me, ‘Oh, make sure you don’t include that in the report, that’s way too intimate. They’re not supposed to be aunties,’ because they were worried about anything that might appear like overstepping. They didn’t know where or how to make a boundary to keep the kids safe. I think that the impulse was very good; still, I don’t think they had to worry about Rad being like an auntie. But I understand why they did.

Constraints as Creative Opportunity

Aaron: We’re running into that a little bit. Perfect City is doing a project called Invisible Guides — Tiffany and Jahmorei are the two artists/working group members spearheading it. It’s a big project with residents at a shelter for domestic violence, survivors and their kids. Privacy is a huge concern, and that actually has become one of the focuses of the project – we isolate people to keep them safe. Some of the residents feel like ‘I’m trapped in this safety.’ There are so many responses like ‘No, you can’t include a picture of someone’s hand’ or ‘You can’t include a picture of the room.’

I’m curious if you’ve run into this in artists working civically– that the constraints become opportunities, as cliche as that is. We think about it aesthetically, like when I worked with Elevator Repair Service. It was like, well, we have these two staplers, and a book and an old office table. We can make a show, and how are we the perfect people to do it? That mindset is starting to kick in with this project now: we can’t take pictures of people, but we’re contracted to do a big outdoor mounted Photoville exhibit with this incredible photographer Destiny Mata; so what we can’t do is our constraint. We take pictures of places where they feel safe. We take pictures of a toy, and then we have them draw maps on it, or whatever it feels like. We do have that ability as artists.

Jan: And as Rad and I also write in that civic chapter, this work is not for everyone. Some artists thrive on those challenges, adore them, and others simply have a vision of something they want to do. They don’t want those obstacles. They want to do their vision. There’s nothing wrong with that; in another circumstance, an obstacle would be perfectly fine but sometimes they’re not going to want to wait, however many hours it takes, to get into the prison, and maybe they’ll get in or not, because really hanging out and watching what’s happening and talking to the prison guards. It’s knowing what you need in order to do a given project. And what the city can let you do. If it is a fit or not.

Would you say more about the project in the shelter for people who’ve experienced domestic violence?

Aaron: The goal ultimately is to propose that people who live in shelters who are the most marginalized by policy are the ideal people to advocate officially for better urban planning policy, better zoning, that kind of thing. Now we’ve been engaged with the shelter for a couple of years, and a couple have they have transitioned into their own homes, and they come back to do mapping workshops with us, and with the current residents. The hope is that some of them actually find career pathways into things like urban planning. We’re positioned for that, at least in theory, because Henry Street’s programming includes job training, so we have a way to ask a little more pointedly now, who should get what kind of job training? That would be my fantasy plan. If it doesn’t go that far, then maybe it’s just like, because you’ve done some mapping and photography with us, you can begin to chart a course to a different career than you maybe thought.

Avoidance Mapping

Aaron: Avoidance mapping has been the cornerstone of what we do. It came really organically; this is another one of my instigator things. I asked the Perfect City working group in an early meeting, ‘What are you an expert at in the city?’ And this guy, Jamel, said, ‘I’m an expert at not running into people I don’t want to see.’ Mallory Catlett was at that meeting, and she said, ‘Can you draw a map of that?’ And he drew this hilarious map of trying to get through Tompkins Square Park without being seen by certain people. There were all kinds of hints about why; some of it might have been safety related, but other [encounters would have been] just awkward, and everybody in New York City and many other places can relate. So we started doing workshops beyond just the group where we asked people to draw what they avoid in their day.

Tiffany and Jamorei had started by looking at street harassment and gentrification as a departure point. They were frustrated that Perfect City’s main activities centered men at first. Then transitioning to shelters, they were, ‘Wow, even for us, for young women of color, this is a different level of avoidance.’ They found that when they asked shelter residents to draw their avoidances, it was a whole bus line or a whole borough. So we’ve done avoidance mapping with, like, the Mayor’s Office to Protect Tenants, and we do it with college students. You can do an Avoidance Map in ten minutes, and different conversations emerge, especially in a group that is mixed in terms of levels of privilege or identity. Like we did one for the Architecture League of New York, and there were white architects who said, “Well, I take the nice bike lane and avoid the one with potholes to get from my loft to the coffee shop, and then to the architecture firm.” And then there was another person: ‘I am a small-bodied young woman of color. I avoid the whole city after ten pm.’ So it’s a tool, an interactive device.

Jan: What is it a tool for?

Aaron: I think for building conversation. A second step has become: what would the map look like if you didn’t have the avoidance? So there’s a kind of belonging mapping that’s come out of it, which I know is not unique to us, but coming from a different way there. Because it sort of lays out who’s in the room. And how do they see the same space differently from me? There’s lots of different ways of doing belonging mapping. From Mindy Fullilove’s work, the book Root Shock, I learned all of us are cartographers from like age three. And separation from a landscape we know leads to different kinds of emotional patterning. But we’re all really sophisticated at mapping.

Expanding Our Circles

Aaron: It brings up another question: What does it do for you, as a practitioner, artist, and/or scholar, to be in touch with the reality that people have who don’t normally intersect with theater or art-making in the way that it’s normally valued – as this separate entity from the rest of life? It does something for me aesthetically and that becomes complicated politically within the field. I’m curious how you’ve navigated that. I’m open to aesthetics that I would not have been ten years ago, because there’s something very valuable in people simply expressing themselves. Our job is to put a frame around that that lets an audience see the conditions and structures behind those aesthetics.

I feel like a lot of work becomes oversimplified. It listens to the community and stops there, which ultimately becomes patronizing. And I think that, both Mal and I, who really love theory, also just love listening to people. The utterances that people make that I understand, or don’t. Those things are really satisfying and beautiful. Bureaucratic language or childlike language or cliché language. It all has valence.

As an artist, one thing I love, I just discovered this yesterday. I was doing flyers for this amazing artist, Flako Jimenez. He’s doing this project at Abrons called Mercedes’ Healing Room, which is dedicated to his grandma, who raised him partly, and who passed from Alzheimer’s recently. And he’s doing all these workshops for caregivers and elders, and he said, ‘We have a couple of workshops to fill. Abrons has flyers. Can you help me?’ First, I emailed some people at different senior centers. But some of them are really small operations and they have a Gmail address, and so no one’s gonna write me back. So I just walked over there, and I dropped off some flyers and had the most wonderful conversations. One place said, ‘Well, all of our elders speak Cantonese,’ and I was, ‘we better do that next year.’ And then I said, ‘But they’re also for caregivers. If they speak English or Spanish, they can go,’ and it was just delightful. I talked to the guy at the front desk. That is something from making City Council Meeting – we had to do that kind of legwork in Houston, in Tempe, in Keene. We went to church services, we met with admin people at City Hall. Walking around chatting with people without necessarily expecting an epiphany or an outcome, and for me that does make it kind of absurd to go to a very rarefied performance, even though there are shows on Broadway and off Broadway that I’m happy to see. It just makes me question the whole way that the field is skewed, the way it operates.

Jan: I sure agree with you that the field is skewed. So many kinds of experiences can be rich for so many reasons, and because we’re so multiple, there are different things we seek in different contexts. As you were talking a couple of images flashed, and one was when I was a kid growing up in a small town and plays were the way I could go to these other worlds that I couldn’t go to otherwise. So I knew I wanted to go into theater because I wanted to get to these places. And then, at a certain point pretty early on, I realized I didn’t want to just go to them in plays. I wanted to actually go to them. There’s still something that happens if you get to reflect and make something out of it. I want both.

I learned something about how different people want different things from performance years ago, when I was teaching theater to fourth graders. I forget what prompt I gave but this kid went up to the front of the room and pretended to go to the bathroom. It’s like, Oh, he’s doing something taboo. Pretending he’s going to the bathroom in front of the class, and they were mesmerized. It was quite a lesson. So paying attention to what’s going on between the performers and the particular audience.

I’m all for people making the kind of work they are drawn to. I really miss performance studies pioneer Dwight Conquergood, because he was someone who, I felt, gave equal weight to the different parts of himself, and that was reflected in how he approached the field, and that was very inviting. Like the way he would go and advocate for gang members because he recognized gangs as families. He really made an impact on me.

Aaron: We are multitudes.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit our website TheCivilians.org.

Authors

-

Jan Cohen-Cruz wrote Local Acts, Engaging Performance, and Remapping Performance, edited Radical Street Performance, and, with Mady Schutzman, co-edited Playing Boal and A Boal Companion. She was Director of Field Research for A Blade of Grass, which supports socially-engaged artists, and directed Imagining America: Artists and Scholars in Public Life. A longtime professor at NYU, Cohen-Cruz initiated Drama’s minor in applied theater and received ATHE’s Award for Leadership in Community-Based Theatre and Civic Engagement (2012). Jan was evaluator for the US State Department/ Bronx Museum cultural diplomacy initiative smARTpower and for seven initiatives of NYC’s Public Artists in Residence (PAIR) t. She is writing, with Rad Pereira, Meeting the Moment: Socially Engaged Performance, 1965-2020, by Those Who’ve Lived It.

View all posts -

Aaron Landsman is a writer, organizer and performance maker . His awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Abrons Arts Center Artist Residency, a Princeton Arts Fellowship, and an ASU Gammage Residency. His projects have been commissioned and presented in New York by Abrons Art Center, The Chocolate Factory, The Foundry Theatre, EMPAC, and HERE and funded by Jerome, MAP, Mellon, Graham, NEFA, LMCC and the National Performance Network. Current work includes Perfect City, a 20-year art and activism collective working on gentrification, Language Reversal, a new theatrical work with collaborators in Serbia, Brazil and Nigeria and Night Keeper, a theatrical work about insomnia as a super power. He teachers at Princeton, has guest lectured at Princeton, ASU, Juilliard, NYU, Bennington and Bard, and co-created the Creative Capital Professional Development Program, was the first Development Director at The Field, and the first grants manager for the award-winning ensemble ERS Theater. He has performed with many artists, across the US and Europe, in Australia and on London’s West End. His book about participation, performance and democracy, No One is Qualified, co-written by Mallory Catlett, will be published by The University of Iowa Press in 2022. http://www.thinaar.com

View all posts