For the R&D In Process series, members of our 2019-20 R&D Group write about their investigative processes as they develop new shows. Jason Tseng wrote this reflection on “Sanctuary” back in February 2020. It will receive a work-in-progress showing at a later date when we can safely gather in person again.

When I started out working on my play, Sanctuary, I thought it would be fairly straightforward. The play focuses on the lives of the members of New Sanctuary Coalition (NSC), an interfaith community organization resisting the detention and deportation system. Conduct interviews, transcribe them, massage those interviews into monologues and arrange those monologues into an evening-long piece. Simple, right?

What I didn’t expect was how deep and immersive the sense of community would become during my investigation. The first thing that my first interviewee encouraged me to do was to attend a training for their accompaniment program, an operation where NSC arranges for citizen volunteers to accompany “friends”—the term NSC uses to describes the immigrants they work with and support—to their various appointments with immigration officials, such as I.C.E. check-ins or immigration court dates.

At the training I attended, I was surrounded by people who had the same concerns and fears that brought me to this project. Wanting to help in what seems like an impossible struggle to keep the families of immigrants together, fearing that you’ll cause more harm than good, worrying you’re inserting yourself into a conversation that isn’t yours to engage in. I was fascinated by what brought all these people who were unaffected by the threat of deportation together to devote their time and energy to something that they would never directly benefit from. That’s where I started at the beginning of the training. By the end, it was a completely different feeling.

New Sanctuary Coalition is fundamentally different from so many “non-profit” or “non-governmental organization” kind of spaces where the model of intervention is paternalistic and centered on those with power. Where I was used to hearing immigrant rights organizations talk about “clients” and “success rates,” NSC used language that not only centered immigrants, but prioritized their agency. I have never been to a training where the volunteers were told, outright, that they are not the heroes of this story. It was a radical inversion of the normal orientation so many of us in the non-profit world are trained to think. We are trained to believe that we are the long-suffering martyrs of the movement. Without our precious contributions, programming, protest, etc. how many lives would be measurably worse? The self-centered kind of charity is the very thing that NSC seemingly wanted nothing to do with.

That’s the kind of charity that maintains the status quo, that presupposes the security of the unaffected over the well-being of the one in need. At NSC, we were asked to take our lead from our friends, to give power and agency to people who are disempowered and coerced at every turn by our government.

By the end of the training I knew that it wouldn’t be enough simply to dramatize the stories of these people; I needed to implicate the audience. Suddenly my play was transforming from something familiar, expected, and comfortable tucked behind a proscenium, to something entirely different—immersive, interactive and vital.

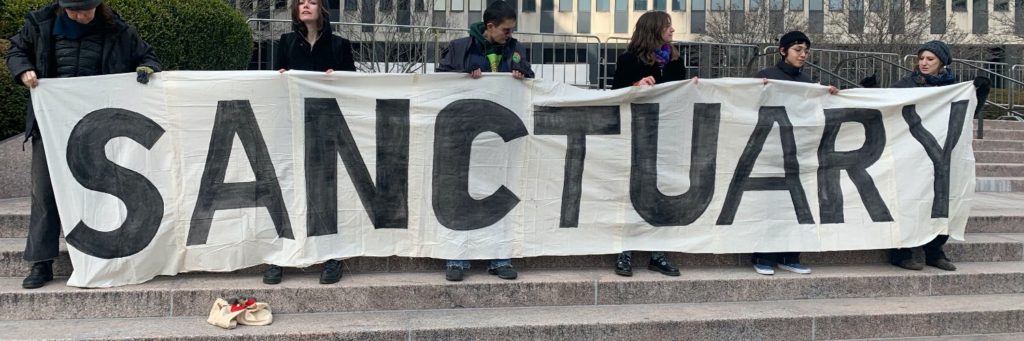

I began to envision an experience where an audience member could enter a performance as I did, gleefully ignorant, and emerge transformed into a part of the movement for immigrants’ rights. I wanted to walk every audience member through the experience of participating in this movement: sitting with a friend at an accompaniment, waiting to hear if their life as they know it will end or be allowed a few months of reprieve; standing shoulder to shoulder in the wintry crisp air at a protest rally; putting their bodies in the way of injustice, desperately attempting to stop what can feel like the inevitable.

I worried that this pivot to immersive was just me chasing a trend. Immersive theatre is, by all accounts, de rigeur nowadays—maybe even played out. It fits in with the instagrammatization of the museum and the elevation of the “experience” over the “presentation.” After all, the once revolutionary productions like Sleep No More now play out as a sort of Westworld-ian romp for the wealthy. I became concerned that my play would cheapen the very stories that I was trying to tell. However, where Sleep No More invites its audience to be voyeurs—revelers in scopophilic delights—Sanctuary invites its audience to be collaborators, conspirators—comrades, even. And that’s something that I can live with.

The other projects in this year’s R&D Group will be presenting work-in-progress showings of their work from May 29-June 29. To attend, RSVP here.

Author

-

Jason Tseng is a queer, non-binary Chinese-American playwright based in New York City, originally hailing from the suburbs of Washington, D.C. Their plays have been presented and developed by Flux Theatre Ensemble, Judson Arts, Mission to dit(Mars), Theatre COTE, Inkubator Arts, Second Generation, Downtown Urban Arts Festival, and LA Queer New Works Festival. They are a Creative Partner of Flux Theatre Ensemble, a member of The Civilians’s 2019/2020 R&D Group, a member of Mission to dit(Mars)’s Propulsion Lab, and their plays have been honored as Semi-finalists for the New American Voices Playwrights Festival and the Eugene O’Neil National Playwrights Conference. Jason’s full-length plays include Rizing (World Premier, Flux Theatre Ensemble), Like Father, Same Same, Ghost Money, Fear and Wonder, and The Other Side. Find more at www.jasontseng.co

View all posts