This piece, “Creating a Platform for Black-Palestinian Solidarity” by Jen Marlowe, was originally published on HowlRound Theatre Commons, on July 6, 2021.

It was October 2000. My seventeen-year-old Palestinian friend, Asel Asleh, had just been murdered by an Israeli police officer. I wanted to respond somehow, to ensure that Asel’s life and the injustice of his murder would have lasting impact. I asked Asel’s older sister Nardin if she wanted to partner with me in in writing a documentary play and began interviewing her about her memories with Asel. I never imagined that fifteen years later There Is A Field would become a framework for exploring Black-Palestinian solidarity.

In summer 2014, as my organization Donkeysaddle Projects was planning a university tour of the play and delving into re-writes, eighteen-year-old Michael Brown was murdered by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. Diving back into the details of my young friend’s murder at the hands of an Israeli police officer, and then watching the Ferguson uprising play out on the news… the parallels felt visceral. My colleague Nadia Ben-Youssef (founder of the Adalah Justice Project) and I began to explore the question: How might There Is A Field draw connections between the state violence and white supremacy experienced by marginalized communities in the United States with that experienced by Palestinians? How might the project strengthen intersectional movements for social transformation?

We reached out to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) for the upcoming tour, anticipating that themes of police brutality, impunity, and structural racism would resonate with students there. Attendance for our first event at an HBCU, Bowie State, was small—perhaps thirty students—but the response was raw. Among the one-word reflections students offered at the end of the performance were: “familiar,” “Baltimore” (where Freddie Grey had been murdered at the hands of police in 2015), “relatable,” and “Tamir” (referencing Tamir Rice, the twelve-year-old boy murdered in Cleveland by a white police officer in 2014). The audience at Bowie State—and later at Howard, Morehouse/Spellman, and Florida A&M—identified dozens of moments in the play that felt connected to their lived experiences, from the police killing itself and lack of indictments to the interactions laced with racism that Nardin had experienced in her university, the supermarket, riding the bus, and at her workplace.

It felt increasingly clear that There Is A Field could facilitate deeper solidarity work than was possible via a performance and talkback. We wanted to use the play with historically oppressed communities in the United States to build a deeper understanding about Palestine, to strengthen analysis around intersectional oppression and freedom struggles, and to solidify a commitment toward mobilization and action.

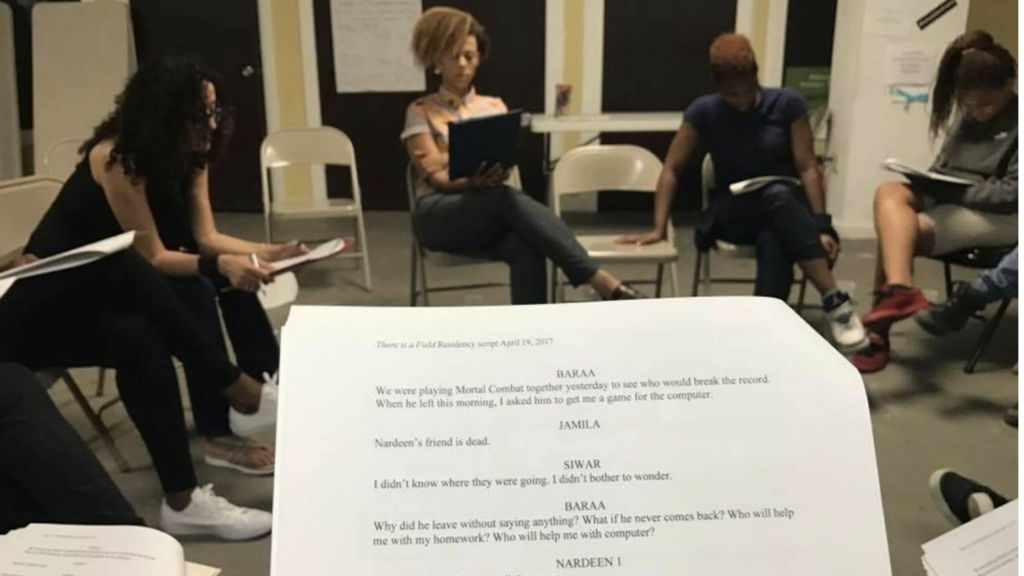

I reached out to Black and Arab artists, activists, and educators to develop a curriculum using There Is A Field as a basis for theatre-based community residencies. Over the next two years, our team led ten residencies in Poughkeepsie, New York City, Tennessee, and throughout Florida, and co-produced a series of staged readings in Washington, DC. In each community, we partnered with a coalition of local racial and social justice organizations. The participants, between ten and fifteen primarily Black artists and organizers per residency, were recruited from those organizations.

Each residency culminated with the participants performing the staged reading for an invited audience of family members, friends, and colleagues. Participants led the audience in a discussion of some of the issues they had spent the week examining, related to the parallels between the story in the play and experiences of BIPOC communities in the United States.

The events also offered an opportunity to elevate local social justice campaigns. In Poughkeepsie, audience members signed a petition, spearheaded by two participants in the group who were students, focused on punitive school policies targeting students of color; in DC, we co-produced a series of staged readings with GildaPapoose Collective as fundraisers for the Black Mama’s Bail Out initiative, raising funds to free six Black mothers from jail. Participants had already spent time discussing Palestinian civil society’s call for the international community to engage in Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS); at the culminating event, audience members were given information about BDS as well.

The residency curriculum was roughly divided into three elements. The first was community/ensemble building—a foundation of both theatremaking and movement-building. The time spent on community building created a space where participants felt safe in becoming vulnerable, both in sharing traumatic experiences of oppression with the group, and in performing. Many of the participants were seasoned organizers but had never been part of a theatre experience. Theatrical warm-ups and exercises offered the participants tools as they prepared to perform, and allowed the group to laugh and play together. We opened and closed each day with group rituals, which created a strong container for their process.

The second element was education around Palestine and exploration of connections between Palestine and experiences of Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) communities in the United States, and the third was rehearsing for the culminating performance-reading of There Is A Field. Each element informed the other: the deeper the participants immersed themselves in the text, the more connections to their lived experiences emerged. And the more the activists grew to learn about and relate to the oppression facing Palestinians, the more they brought their own realities to the characters they were embodying.

The program was at its strongest in achieving its goals when we integrated those elements into each activity. One activity was built around the “Four I’s of Oppression,” a framework sometimes used to analyze oppression as four intersecting forms: ideological, institutional, interpersonal and internalized oppressions. We typically engaged in this exercise on day three of the residency, after participants had read and discussed the script together, learned some context around Palestinian history, and done some Theatre of the Oppressed–inspired tableau work.

We’d begin by laying out four cards, each with an “I” written on it. Participants discussed each “I” together, coming up with collective definitions and examples. Then, the participants split into four small groups, each with one “I” card, and had to identify one moment in the play they believed best exemplified the form of oppression on their card. Then, they had to create and share a tableau that illustrated that moment. The spectators guessed which scene from the play they were looking at and which form of oppression that scene represented. Invariably, the interlocking nature of the oppressions would emerge. For example, a tableau of Nardin’s university classmate justifying the murder of her brother relates to interpersonal, ideological, and institutional oppression.

Participants were invited to share personal stories that came up for them as they watched the tableaus. A tableau of the moment Asel was executed reminded one participant of her friend Reefa, an eighteen-year-old Colombian immigrant and graffiti artist, who was murdered by the Miami police. Another participant, in response to a tableau of a Jewish Israeli shopper assaulting Nardin in the supermarket, told the story of an overtly racist interaction she had had with a gas station clerk.

With the storyteller’s consent, we asked the other participants to make a new tableau of their story. The storyteller offered feedback about whether the tableau captured their truth, made any changes they wanted, and expressed how it felt to look at the tableau of their story. The storyteller usually expressed amazement at just how accurately the tableaus represented the essence of their experience. Next, the storyteller got to share whether they had been able to resist the oppression they experienced in any way, either in the moment or afterwards, or if there was an act of resistance they wished they had been able to engage in. The young woman with the gas station encounter spoke about the song she wrote after returning home. The other participants then made a tableau embodying that act of resistance, and invited the storyteller to enter the tableau herself. Finally, we asked whether these tableaus of resistance brought to mind any moments from the play and, if so, which ones.

In this way, we went from a theoretical framework about oppression, to moments in the life of a Palestinian family, to personal memories about experiences of racial oppression in the United States, to exploration of resistance in the United States, to exploration of resistance in Palestine—all of which were embodied by the participants. This activity provided the foundation for connecting visions of liberation that we usually engaged in towards the end of the residency, where we created group tableaus and soundscapes around the theme of liberation.

Social justice organizers are often extremely clear on what oppressions they face and their preferred tactics of resistance. Far less often are they offered space to imagine what the liberation they are seeking could actually look like, much less feel it in their bodies. Moving from an embodiment of oppression to resistance—and then transforming tableaus of resistance into liberation—collectively nurtured the participants’ radical imagination, a critical tool of social transformation.

One extremely powerful residency was organized in partnership with the Eagle Project, an inter-tribal Indigenous performing arts company. Half the participants were Palestinian activists/actors based in New York City, the other half were actor/activists indigenous to Turtle Island. We adjusted the curriculum, anticipating that the parallels and connections that surfaced might be different than some of those that surfaced with primarily Black organizers.

The connections explored in that residency went straight to root of the oppression: settler-colonialism. The participants performed There Is A Fieldand two shorter pieces, one by Ryan Opalanietet Pierce, a Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape playwright and actor, and one by Ty Defoe, an interdisciplinary artist from Giizhiig, Ojibwe, and Oneida Nations. The participants spent hours educating each other on the impacts of settler colonization in their families’ and communities’ histories, including the traumatic legacy of the Indigenous boarding schools. The rehearsal process and the culminating event were themselves acts of decolonization. We hoped that through the learning and relationships gained, more decolonizing art would be created and a deeper vision of a decolonized future could be imagined.

In August 2018, we invited twelve activists from previous residencies to gather at the Peñasco Theatre Collective in northern New Mexico. We spent six days together, going deeper into script work, discussion, and analysis, and filming the performance. This became the basis of a There Is A Field documentary film that premiered on 2 October 2020—exactly twenty years after Asel’s murder.

Throughout this entire process—from the tour, to the residencies, to filming in Peñasco—I was keenly aware of my own positionality as a white, Jewish person. I am committed to anti-racism and decolonization, and I consider myself an anti-Zionist, but it felt complicated to me from the start to be leading a project around Black-Palestinian solidarity. Even so, it wasn’t until the film’s premiere that some of my blind spots were revealed to me. The play’s (and now film’s) critique of Israel’s violence is primarily through a lens of citizenship. And, though Asel did hold Israeli citizenship, his family’s struggle is not one of equal rights as citizens. It is a liberation struggle against settler colonization.

I also am only now investigating whether audiences come away from the film with a too-rosy view of the encounter-based peace organization that Asel was a part of. The project seeks to further solidarity between communities struggling for liberation. I’m concerned that those scenes might inadvertently reinforce a message about the importance of “coexistence,” which is part of problematically normalizing relationships between the oppressor and oppressed groups, rather than one of dismantling power and privilege.

Though it’s too late to alter the film in any significant way, I hope that post-screening conversations and accompanying resources can address some of those issues and sharpen framing.

The connections and conversations with the residency participants have continued long past the residencies. In response to the recent escalated violence in Palestine from Israeli military and settlers, the Palestinian Performing Arts Network (PPAN) put out a call asking for theatre companies in the United States to take a stand in solidarity with Palestine. Artists and organizers from the Eagle Project/Donkeysaddle Projects residency are now discussing the possibility of offering roundtable discussions for theatres that want to answer PPAN’s call, focused on how their art and collaboration is part of resistance to settler-colonialism. And a group of Black, Palestinian, and Indigenous artists and activists who came together in early stages of developing There Is A Field curricula created a new collective and have been crafting a performance piece of vignettes based on their families’ histories of settler-colonialism and its impacts. The vignettes are in their final stage, and a version of them will be performed virtually in the near future as a fundraiser for people in urgent need in Gaza.

There Is A Field is fostering connections and conversations, and is mobilizing action between activists and artists who are part of different communities engaged in liberation struggles. This is among the most meaningful impacts of Asel’s story that I could hope for.

To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, join our email list at TheCivilians.org.