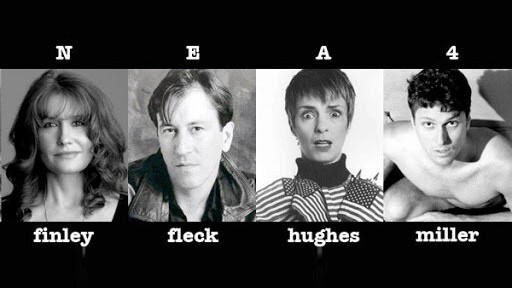

To scholars of queer 90s art, the name Holly Hughes will be a familiar one. Hughes, along with fellow experimental artists Karen Finley, Tim Miller and John Fleck, was part of the notorious “NEA Four,” whose Supreme Court case marked the end of individual artist funding. In light of recent struggles between artistic institutions and the NEA–and its attendant administration–Extended Play sat down (virtually) with Hughes to hear their thoughts about the intersection of practice, politics and personal identity.

Interview transcript has been edited for clarity.

Faith Zamblé

I suppose my first question is, when you were involved in the NEA case, what did that feel like? Did it come out of nowhere? I’m curious about the context of that moment in your life and your career.

Holly Hughes

Well, I mean, it didn’t come out of nowhere in the sense that, about a year before then, Senator Alphonse D’Amato was tearing up catalogs of Andres Serrano on the floor of the Senate. You could see what was brewing, and you could see that for a long time, the right wanted to get rid of the NEA and public funding in general. Ronald Reagan tried, but he didn’t get very far because a lot of well-off people–even Republicans–were art patrons and they blocked it. But [eventually] the right found a great sledgehammer by weaponizing all of the homophobia and [cultural] anxieties of that time.

How did it feel at the time? I mean, it was a pretty isolating and upsetting experience. None of us were part of any institution, and the conversation in the public often turned to, “Well, these artists aren’t very good anyways.” And it was brutal. It was like a bad review every day, hate mail, death threats. I kept thinking when the press would approach me, I would be able to say something that might change things. But, you know, all the questions were framed to support a different narrative, one about what had I done wrong. To put it into perspective, at the time that this happened—1990—the New York Times would not say the word gay or lesbian in the paper. They would say homosexual, but reluctantly. So, I was like, “This is about homophobia. That’s all it’s about.” They didn’t even know my work, not that I thought they would like it, but I knew their narrative was fueled homophobia, and I just couldn’t get that story out. People were so rabidly anti-gay at the time, and there was this whole hysteria that came out of AIDS. I see a different version of it now with the conversation around trans rights which is just terrifying.

Faith Zamblé

And so heartbreaking. It’s wild to watch people go through this again. It feels like it always comes back to “gender ideology”–which is a great punk band name. Maybe some of these people should be making punk music instead of running the government…

Holly Hughes

I have thought that “gender ideology” would be a fun name for something,

Faith Zamblé

Right? I mean, it writes itself (sort of). Were you a part of a larger artistic community that supported you during the time of the trials? How did you get through that experience in one piece and then continue making work?

Holly Hughes

Well, I had started making work because I was part of a lesbian theater company, the WOW Café, which still exists, on E 4th Street. I went to something at the Club 57 which was this, like short lived club on St. Mark’s Place in the basement of a Catholic church, and it ran for a couple of years. I mostly didn’t go there because it was more of a boy’s scene. But I did go a few times, and we had some events there. And I realized, “These are my people!” I wasn’t as much involved in WOW by 1990 as I had been in the early 80s, but I still had a circle of friends who had my back. But the hardest thing was seeing myself or other people being attacked in what you would think of as alternative media. Not so much the Village Voice, more like The Nation. And that led me to feel extremely isolated. There was a small group, I think, who fell prey to the idea that there’s no such thing as bad publicity. And yeah, my name was in the press a lot, but it’s in the press as, I’m a pedophile, or I’m connected to these undifferentiated charges of some kind of moral failing.

Faith Zamblé

Isn’t that libel?

Holly Hughes

In England, it would have been. There was a thing in U.S. News and World Report by this columnist David Gergen who used to be on CNN a lot. I think he might have retired. He said that during the piece that I was doing when all this happened, I stuck my hand in my mother’s vagina on stage. And I mean, the piece was about my mother, who was dead, and I did talk about her sexuality, but the idea that in my solo show, I stick my hand in my mother’s vagina is just absurd.

My lawyers reached out to U.S. News and World Report, and they printed a retraction the next week. But the same kind of thing would happen again and again. In some ways, it was a little comical. There were moments of comedy in it, but it honestly was very scary. We were lucky to have legal representation from the Center for Constitutional Rights and the ACLU; they were very involved, and it was pro bono. But, lawyers aren’t social workers. It’s not their job to make you feel better while you’re falling apart. You could have just had some devastating moment, and they’re like, “Oh, you were so great. You were so great in the deposition.” So, it was a bad time for me personally.

At the same time though, the whole thing was so impersonal. Nobody cared about my work, per se, other than the fact that it had queer content in it. It was about attacking the arts as a whole and making an example of us. And, they really took a sledgehammer to the NEA, and [there’s] certainly no more individual artist funding. I think in general, the entire amount of artist funding is greatly reduced. And part of the reason why it happened is between larger cultural institutions and public intellectuals, nobody banded together to say, “This is terrible. Stop!” The only way that that happened was with writers, who still have funding. There are still fellowships for writers, and it took a bunch of people in publishing, including people that had probably never gotten NEA money, like Stephen King, John Grisham, taking a stand on the NEA. Meanwhile, the silence was so deafening from major cultural institutions and the little ones that spoke up usually got smashed like Franklin Furnace.

Faith Zamblé

You’re saying that major museums and galleries said nothing?

Holly Hughes

They said nothing. They really were silent during it. There were some Hollywood types who were kind of involved during this time like Christopher Reeves. But they didn’t talk about the work that was under attack. They wouldn’t defend the real issue: that we have to support art that’s provocative and raises questions as art has historically done. I’m seeing the same things play out with universities.

Faith Zamblé

How do you think the cutting of this funding has created the arts landscape we have now, and considering your position at a university… What is that like?

Holly Hughes

Well, I mean, I think the universities have been in the sight lines of the right wing for a long time, and they’re just ramping it up. The biggest parallels that I see is that they’re weaponizing certain ideas, some of which are entirely made up, like the idea that there’s this glut of trans women ruining college sports or women’s sports. And you know, anti-Semitism is definitely a real thing, but the meaning of it has changed so that any critique of Israel is considered anti-Semitism.

Faith Zamblé

Which is not the case.

Holly Hughes

No, but they’re using that to support these cuts that they’re proposing… which are devastating. I mean, the Ivy League… Columbia is still going to exist. I don’t know what’s going to happen to the medical research though. The universities are not quite the hotbed of radical thought that the right imagine, but they are a home, or more of a safe place for people who are asking big questions. There’s money at the university for me to do my work, and I look in the world outside, and there’s just not very little money.

At the same time, I don’t think the universities have always been very radical. I mean, they were pretty horrible in the 60s with, you know, anti-war protests; they were pretty bad with the anti-apartheid movement. You know, my partner is quite a bit older, but she was a red diaper baby. And when she was an undergrad here at the University of Michigan, the Red Scare was in full force, and there were entrapments in public bathrooms, and people would get their names published, some of them lost their jobs, and some of them killed themselves. The university is mostly interested in preserving itself, and at a place like Michigan, which is like a pretty well funded public institution, it’s really run by the Board of Regents, who are elected wealthy people for the most part.

Everybody’s waiting on bated breath to see what happens with the funding from the NIH and the NSF, which doesn’t just go to STEM fields. That’s primarily where it goes, but the school takes a portion of that to support things like me doing a performance piece that’s not going to be patented.

I have a colleague here who is in the medical school. She researches and does gender affirming care and all her funding just went away. So, I get that people have a reason to be afraid. But I keep thinking, perhaps if universities had any solidarity with each other, if there were university leaders pushing back on some of this, they could actually make some changes. I’m lucky to be here at the university and appreciate things about it, even if it is in the middle of a cornfield.

Faith Zamblé

What do you think it would take to get universities to band together and engage in some sort of collective action? Do you think that’s something that could happen?

Holly Hughes

It could happen, but I don’t think that it’s going to happen. The only university leader that I’ve seen who’s pushing back on this is Michael Roth—the president of Wesleyan. The mode seems to be “put your head down, save what you can.” I don’t agree with that, but in conversation with some staffers, they’re saying, “I’m a single mom. I can’t lose my job.” So that kind of fear, which is real, doesn’t lead to bold action.

I also think people are so demoralized from the return of Trump and the fact that that could even happen. Despite all of this activism that happened in 2017, we’re back worse than ever.

Faith Zamblé

I find myself both demoralized, but also confused at being demoralized, because when I think about the response to the AIDS crisis and or even the Civil Rights Movement… There are so many moments in history where things have been very bleak and people were willing to take a stand of some kind and make work from that place: it feels like many people are too demoralized to do that, even though we have access to more information than people ever have. So, I’m wondering: what do you think has changed? Is Trump really that bad? Like, worse than Reagan?

Holly Hughes

Reagan was really bad, but Trump is really taking apart the country. I really didn’t participate in the civil rights movement; I was too young, but I was around for the fight against AIDS, and it took a while. It took a while for people to get themselves organized. ACT UP happened six or seven years into the epidemic and was unpopular when it was going on. It was really a Vanguard movement that didn’t try to be something that everybody wanted to join. So, even living in New York City, lots of gay people were like, “I don’t like ACT UP and blah, blah, blah.” They were really provocative, and I don’t think everything that they did worked, but I think in the long view, it was incredibly effective.

Faith Zamblé

With that, I also was going to ask you, how are you navigating your own artistic practice now? How has it shifted? Are you excited about making things?

Holly Hughes

I am excited about making things! I just got some funding at the university to develop a new performance piece with Katie Pearl, who’s half of the Pearl Damour theater company. There was a bee in my bonnet a while ago with the Christine Blasey Ford testimony and I was doing tons of research about what I could say that’s new about this. I couldn’t find my way in, but now I’m working on this piece. The conceit of it is that I am both myself– Holly Hughes, a septuagenarian lesbian performance artist–and a private detective who’s been hired by Christine Blasey Ford and Anita Hill to investigate all the crimes of the patriarchy. And they picked me because of my devotion to BritBox mysteries, believing that I would finally be able to crack the case. I wanted to deal with difficult material, but I also wanted to inject some humor and into it, which is really tricky, but I’m having some fun working with Katie on it. That and going to see live weird shit; nothing makes me happier.

Faith Zamblé

There are so many people who actually would like “weird live shit” and just don’t know it yet. But I also think conservatives have been able to exploit the fear of difference as well as, the confusion that people have about what performance art is and what performance artists do. They’ve used the fogginess of it all to say, “See, while you’re working your nine to five, these so-called artists are covering themselves in peanut butter!” How you would argue for the importance of experimental work—for the importance of weird stuff—to somebody who is not in the arts?

Holly Hughes

I would start with the fact that human beings are hard wired to like novelty, to like new things. We’re always balancing some sense of safety and stability in our lives versus looking for new things.

Unless you’re living in an ultra-orthodox community, or something of that nature, there’s out of the box, weird, edgy stuff coming at you all the time through your phone, on the TV, in movies, certainly in popular music. I think human beings and human culture is always changing. It’s never static. And some of the ideas that we see as commonplace and almost cliche today were new and shocking ideas a few years ago. One of the powers of the arts is to raise questions, to move us, to get us out of our comfort zone, so we can consider something else.

I think people are wrong when they say they don’t like experimental art, because mainstream art is always cannibalizing and co-opting stuff that bubbles up from the margins and maybe shaving the edges off a little bit. It’s always happening.

There isn’t a one and done persuasion point to get across to somebody who feels weird art is useless and terrible. Life is full. It’s full of a lot of things that you can’t even comprehend. I’m never gonna climb Mount Kilimanjaro. I’m not gonna go to most places. But I’m glad they exist, right? ✦

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.