Hi! We’re Eric Marlin and Lila Rachel Becker, and we make plays together as Portmanteau. UNTITLED JEWISH PIRATE PLAY is our third full-length project together, and the first that we’re co-generating. We interviewed each other about the process we’ve undertaken as part of the R&D Group, and how this work is new and different for us.

LRB: What drew you to 15th century pirates and this specific moment in history?

EM: I think you were the one who first found a tweet about the Jewish and Muslim pirates working together to battle their enemy, Spanish Catholics. That description was irresistible! Who doesn’t love that story? Before encountering that tweet, I didn’t know there were Jews who became pirates after fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. Part of the pleasure was the not-knowing, that there was this rich historical moment that didn’t fit in with the usual Jewish narratives I heard growing up. I’d also had a somewhat longer interest in the Convivencia, and the history of the conversos and crypto-Jews in Spain after the Inquisition began. I’m fascinated by the sense of upheaval in this time period. Kingdoms are shifting, religious identities are shifting, power centers are shifting. A crypto-Jew is not the same as a converso or a New Christian, and none of these identities would’ve made sense 300 years prior when there was a more fluid cultural exchange between Muslims, Jews, and Catholics in Spain. Piracy is itself a fluid and fragile identity. Legality, national alliance, sexuality – all are in flux for pirates, which makes them an intriguing parallel for the larger cultural and religious shifts happening across Europe and the Ottoman Empire in this time.

LRB: Can you walk me the steps that you went through in the writing of this play? How did it evolve from idea to script?

EM: First there was a fairly wide-ranging research process. We looked at the history of Jewish pirates, piracy more broadly, the Inquisition, converso & New Christian identity, and pirate movies. When it came to the writing process, there was a lot of iterating. This play needed to be maximalist, playful, physical, which is all very different from what I usually write. And as wonderful as all the research is, I found it difficult not to get weighed down by it in the early stages. The first pages felt self-conscious, wanting to put down all the ideas we were discussing and facts we had found in this very deliberate manner. This approach killed the looseness and sense of fun the play really required. So, I scrapped that version and tried three new approaches. One focused on everyone but the pirates, and was about the currency of myth and storytelling. One was tightly bound to life on the ship, and used a conceit of skipping ahead in time every few pages to create momentum. And the third was a kind of pirate vaudeville that riffed on cliche and stock imagery in a crude manner. Once I got those ideas out of my system, I took some of the most interesting kernels from each one, and began crafting the play we have now. Those abandoned versions of the play were crucial; they helped me find dramatic language for the research.

LRB: How does writing a play based on historical research differ from writing a play without research? Do you usually do research for your plays?

EM: I rarely do formal, intensive research like this for my work. However, I almost always have a text or article or image that I’m bouncing off of for my play (a poem, a Biblical story, an essay on globalization). I like having something concrete to work with; then writing becomes more like a game rather than trying to drudge something out of my own soul. But since I’m usually not bound by what I’m adapting or responding to, I only have to use what is fruitful. For me, this process was unconventional in the intensity and breadth of the research process before I’d even written a word. I had to muck with the research in a way that made it feel less overwhelming, to get it to a place where it felt like something I could play with. I wanted to be respectful of this world and time period, but I could only do that if I wasn’t working from a place of dutifulness.

EM: What’s been your experience through the research? Both in terms of process and what you found out?

LB: Researching this project was a lot of fun! Who doesn’t want to watch a bunch of pirate movies? Lots of what we found was surprising. For example: a bunch of the pirate movies I remember with fondness are actually really boring! I learned that a lot of my cultural touchstones for pirates are actually pretty different from the pirates of the period we’re focused on. The 18th century English pirate ships of Treasure Island and Pirates of the Caribbean are structured much more like the English military of the time than the pirate ship that we’re writing about would have been. 15th century pirate ships resembled early democracies, with many languages and cultures aboard. It’s been a real pleasure to have so many of my assumptions upended and complicated.

As for the process, it hasn’t looked all that different from the kind of research that I do for other plays I’ve directed. I often immerse myself in the world of a play I’m directing: reading articles or novels, listening to music, and looking at photographs and paintings. The major difference is that often I’m working with a playwright who has a bunch of research done already, and that becomes the seed of the research that I conduct. On this project, we embarked on the research from scratch, together.

EM: How does this project align with your previous work? Where does it intersect and where does it diverge?

LRB: I’ve directed many plays that were set in a specific period from the past, but I’ve rarely been strict about being accurate to the period. I don’t have anything against period productions, but for my own work, I’m often interested in the rules and manners of the period only so far as they have something to say about the time and place in which I’m directing the play. With this play, we’ve been very deliberate about trying to understand the traditions and society of the characters that we’re writing about. One of our goals with this project was to create a play with Sephardic (Iberian and North African) Jewish characters rather than Ashkenazi (Eastern and Western European) Jewish characters. There’s a strong bias toward Ashkenazi culture in American depictions of Jews, despite the significant cultural differences between these two groups. There’s a ton of diversity within Judaism. We’re both Ashkenazi, and our past work that engages with Judaism has intentionally focused on Ashkenazi Jews. So with this project, we’ve been rigorous about troubling our assumptions about how 15th century Jews practiced, and tried not to read our contemporary Ashkenazi Judaism onto the characters. Being accurate in our research feels important to the project of the play.

EM: You have been involved in the generation of this project, which is new for us. How has your directing practice informed your work here?

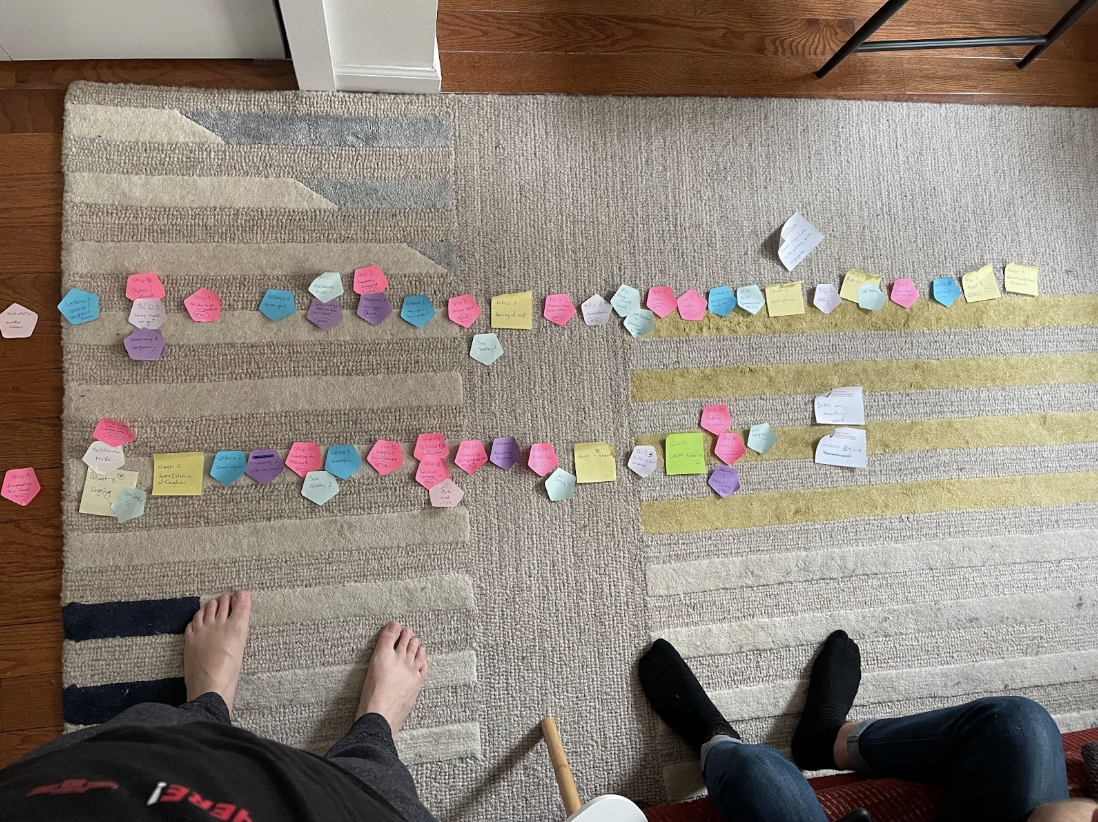

LRB: Overall, this process has felt to me somewhere between a devising project and traditional script-based play. We’ve figured out a lot of the big picture ideas in the play together, but you’ve been the person doing the moment-to-moment work and figuring out who is in the story. For me, it’s been really exciting to be able to participate in the play at the storyboarding level. For example, recently I had a lot of fun working with you to figure out the pacing and how the different storylines intersect and overlap. (See photos below!)

As a director, I’m always thinking about production. The script is only a piece of what I’m imagining at any given moment when I’m working on a play. There have been some really interesting moments in the process so far where questions that you’ve flagged as script questions feel more to me like production questions–the script actually cannot answer them because we won’t know quite what they are until we can collaborate with actors, choreographers, composers, and designers. At the moment, all we can do is articulate what needs to happen at each moment in the play to move the story to the next moment and add a piece to the larger puzzle we’re creating.

I’ve been pushing for some questions to remain unanswered in the writing process, because I think that this is going to be a play that finds itself in the rehearsal room. UNTITLED JEWISH PIRATE PLAY has swordfights, shipwrecks, music, intimacy–a lot of storytelling that will happen non-verbally. These dynamic movement sequences and adventure montages are quite different from anything in the projects that we’ve created together before, and that’s very difficult to capture on the page. I’m excited to get into the rehearsal room in June, because even though we won’t be rehearsing a full production for the Findings Series, I think we’ll learn a lot from what actors will bring to the project.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Authors

-

Eric Marlin (he/him/his) has been produced and developed by the Public Theater, Theatertreffen Stückemarkt, Ars Nova's ANT Fest, the Civillians, Edinburgh Festival Fringe, The Tank, Dixon Place, Samuel French, HOT! Festival, Exquisite Corpse Company, PTP/NYC, Tennessee Williams Festival, Play Date @ Pete's, and Wildclaw Theatre. Winner of the Samuel French OOB Short Play Festival. Finalist for SPACE at Ryder Farm, the Jewish Plays Project, and two-time finalist for the O'Neill National Playwrights Conference. Current member of the Civilians' R&D Group. Former Resident Artist at Montclair's New Works Initiative. MFA: Iowa Playwrights Workshop. BA: Bennington College.

View all posts -

Lila Rachel Becker is a DC-born, NYC-based director and one half of the theatre collective Portmanteau. She has directed and developed work with theaters all over the country, including Actors Theatre of Louisville, Woolly Mammoth, Portland Stage Company, Williamstown Theatre Festival, The Tank, Folger Theatre, and the Source Festival. Recent productions: and come apart by Eric Marlin (Portmanteau + The Tank); THREE SISTERS by Anton Chekhov (University of Iowa); bad things happen here by Eric Marlin (Portmanteau + Edinburgh Festival Fringe); CLARABELLE, 86 by Anna Fox (Cloud City). Member, LCT Directors Lab, Directors Lab North. BA Wesleyan University. MFA University of Iowa. Associate Member, SDC. lilarachelbecker.com

View all posts