Faith: I’m really excited to talk to you about your work and [your] Next Forever thoughts! My first question is… How you would describe yourself and your writing? Which is such a big question..

Kate: Well, I have, in just the last few years, started using this tagline of “countercultural plays for fun-loving audiences.” That captures something encompassing about what I do, which is that I’m interested in rebellious characters who are, in some ways, just not in sync with the mainstream and super capitalist values, and who are maybe a little rough around the edges. Characters who are in some way or other marginalized, but who find their way through it. And I’m definitely someone who’s very playful and interested in trying new things with form. I feel like a millennial writer who’s been trying to write theater [that] appeals to her generation where so much of the theatergoing audience is typically much older, of retirement age. I’m trying to write in a language that’s current and has a hip sensibility.

Faith: What I find so compelling about this description is the emphasis on fun and fun-loving audiences, because I think sometimes plays are written for audiences who really need to learn something. Was that always part of your artistry and worldview? And with that… how did you come to writing?

Kate: Oh, no, I hate that question, because that’s a really long story, and I somehow haven’t figured out how to tell a short version.

Faith: So… we’ll just skip that. One day you started writing, and then…

Kate: I do think fun-loving has always been important to me, it’s just part of my sensibility. My sense of humor is a huge part of how I process the world. I also grew up in a military adjacent family, so I grew up in Germany, and my mom worked on a US military base in a tech capacity in the world of IT. So she’s not military herself, but I always had one foot in the military world and the other foot in this very small, remote German village that I grew up in. So, I mean that alone…

Faith: Yeah, that that’ll do it…

Kate: Honestly, both of those worlds were very hierarchical and not fun. And the military also… There’s an officiousness to it, an official mission tone that’s so serious, and every bit of communication that you encounter is about maintaining this official tone. It’s funny that that’s where my family ended up because my mom is also an extremely rebellious personality. So, I think there’s family reasons for why I am the way I am. But, yeah, I definitely think growing up in these two very hierarchical serious cultures activated the rebellion in me, and that’s never going away.

Faith: As it should have. I think we need that in a very big way. And it’s funny, because Germany is pretty hierarchical, but I do feel like they have a love for weird and chaotic things. Do you feel like that influenced your sensibility at all?

Kate: I mean, I went to German kindergarten through ninth grade, so obviously, German culture has played a significant part in shaping me. But I do think there’s this sort of funny thing that happens where I say I grew up in Germany, and then people in the arts have all these associations of Berlin and, you know, wild and crazy artistic experimentation, and that was not my world. I really grew up in a very remote village in the woods where, I would say, playing in the forest informed my imagination more than seeing theater, which I saw very little of. As a teen I did see a lot of German Expressionist painting. I actually wanted to be a visual artist before I wanted to be a theater person. I was seeing more expressive, very color rich, strong point-of-view paintings. But, yeah, living more rurally, I experienced more of this other side of German theater culture where, like, for example, there’s a town, Bochum, where the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical Starlight–

Faith: Express. Oh, my God. I’ve just been reading about this. So wild.\\

Kate: I’m gonna misquote the number of years [it’s been running]. I’m gonna guess 20?

Faith: I think it’s like 20, 30 years.

Kate: I feel like that is the kind of theater world that I had any exposure to growing up—the occasional Andrew Lloyd Webber musical.

Faith: Starlight Express being a hit in Germany is so mind boggling to me. Starlight Express existing at all is mind boggling to me, but it seems fun so I don’t know…

Kate: A family-friendly show, yeah.

Faith: Trains on skates… fun for everyone. What a time. Okay, so I’m curious about your writing process, and how that has come to bear on your proposal for The Next Forever. The real question here is: what is Topia? What is Topia about?

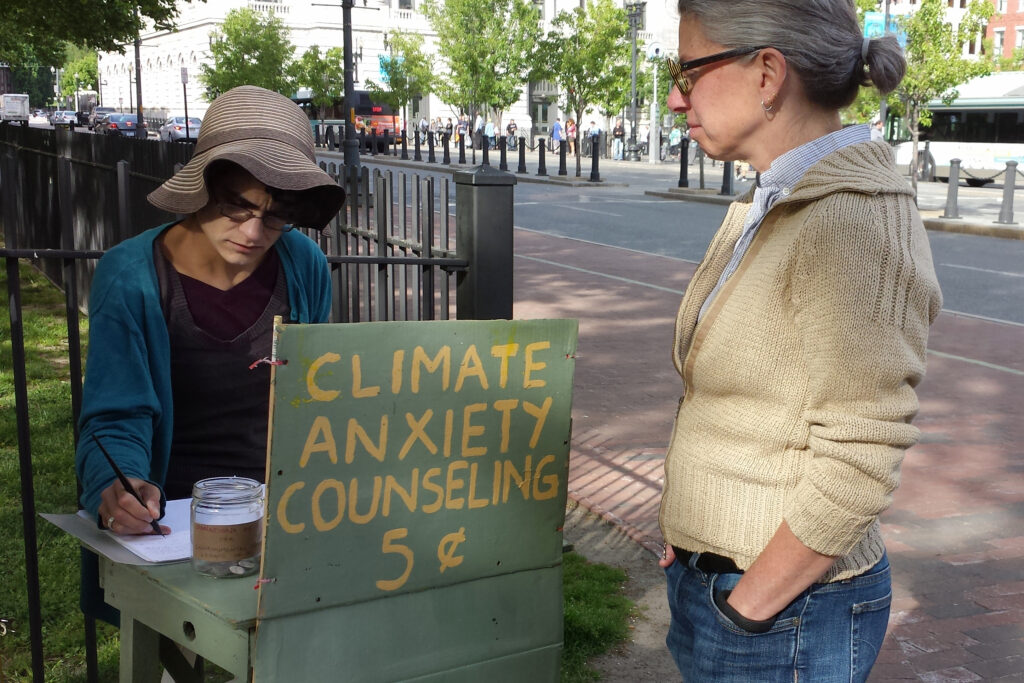

Kate: I don’t want to do spoilers, and I change things as I’m doing research, but the things that won’t change are that it’s a multi-generational story about climate transition set in Providence, Rhode Island. It looks at both [a] best-case scenario and a worst-case scenario for a climate future, both a utopia and a dystopia, and at the center of it is a… This is where I don’t want to give too many spoilers! But, it’s about two women searching for each other across rapidly shifting realities, and is really interested in: How much can we save? I think [the] animating question for me is: How good of a future could we still have? And also, [as] a challenge to myself, a desire to imagine forward into something positive and ask some nitty gritty questions about, how could we get there, because it’s inevitable that we need to have an energy transition. My question is, how much loss and pain and destruction will we tolerate on the way there? I’m very interested in something that was actually articulated within The Civilians’ call for proposals as well, with a Naomi Klein quote around imagining and about how the stories we tell ourselves around climate are foundational to how we address this crisis. I’m very interested in how what we allow ourselves to imagine shapes what ultimately becomes possible in the real world. Which we just saw so intensely with Biden and Harris, where we had all these pundits saying, “It’s a West Wing fantasy to move to another candidate!”

Faith: [And] A week later…

Kate: We did it. So that’s something that I’m really interested in–how we imagine. And I think however I ultimately structure my play, it’s going to really emphasize imagining, and the actual characters trying to conceive of futures and pasts and [shifting] their own worlds by doing that.

Nobody knows the future and that is one of the things that does still give me hope.

Faith: I am really interested in this idea of utopia, because I think that is not something that we see a lot on stage. I don’t know if it’s because of the Greeks being like, “Here, we’re going to show you the worst-case scenario every time.” I’m curious on your thoughts [as to] why we don’t see more utopias, but I’m also wondering what Utopia means for you.

Kate: My fun-loving, down-to-earthness is going to give this play a different flavor than a lot of sci-fi tropes we have around what a utopia is or what a positive vision is. I think one of the pitfalls of dreaming forward is that imagining perfection can easily become cloying and deadly in its glossy vagueness, and fundamentally unreal in its depictions of human behavior. And I don’t think I’m actually interested in perfection, per se. I’m just interested in a world in which we don’t go–

Faith: –extinct. That would be nice.

Kate: [A world where] we do transition off fossil fuels, adapt our cities to a changing reality, and enact policy changes that benefit more people. Part of this process has me wrestling with what is a utopia, and what is dystopian? What are our tropes around this? What are our lazy habits of imagination around this? In terms of the theater, you know, I do think there has been a bit of a shift. I feel like I have been seeing more playful, joyful, “searching for a positive vision” kinds of stories. But yeah, I mean, it’s hard, I think because the stakes feel so high and just so many aspects of public life are in crisis in the United States. We have eroding civic institutions, and obviously with this election coming up, we’re facing a coin toss of what world are we going to be living in? I don’t want to be Pollyannaish either. But, culturally, often we don’t trust joy, we don’t trust pleasure. Certainly, we don’t fully trust it on stage yet. Just think: We too could have Starlight Express.

Faith: I also think that finding the balance between joy and escapism is hard in these times, and I don’t know, I do wonder if that’s why sometimes people don’t trust joy because they’re like, this is just a distraction. Also, I don’t know, I like the idea of Utopia not necessarily being this trope where it’s like, flying cars and everything’s great. It’s like, no, maybe we’re gonna get rid of prisons, or, we’re just gonna have reparative restorative justice.

Kate: Or, affordable childcare. Like, hello. My vision of American utopia, it’s just… having the essentials of what we need. Just the basic things, you know? I mention childcare because [I’m] interested in trying to imagine a future that you would want to have a kid live in. It’s become its own sort of trope, of people not wanting to have children because of global warming. I think it’s actually more complicated than that, or nuanced than that. People are people. It’s economic calculations, plus climate uncertainty and fear. It’s: “Am I really gonna put a kid into this world where they can get shot in school, and I don’t know that I can afford childcare, and I can’t afford a house?”

There’s a global phenomenon too. It’s not just the US that we’re having this decrease in reproductive rates. And there’s obviously conversations to be had about [why] that’s not necessarily all bad, either. But also, but also an invitation to [ask], why is this happening? What are all the whys?

There’s a certain danger in having one person put forward a vision of utopia.

Faith: Absolutely. So now, I’m wondering, had you been thinking about Topia for a while? How did this idea come to you?

Kate: I have been thinking about it for a little over a year, I would say. It came out of me asking personal questions about where we’re going and whether I want to opt into having children, whether I can afford to opt into having children, or… less ambitiously: [a] child. And like I said, I grew up in the woods, and in a country, Germany, where an environmental sensibility is a more central part of the culture. I’ve written or worked on plays about climate change and climate crisis since college… not continuously, but it’s a topic I keep coming back to. Even in my plays where it’s not the foregrounded topic, it still gets woven in, typically, in some way or other. At this point, I want to dive deep into this subject, and I’m really excited to do it in this with the support of this grant, which is going to let me be so much more ambitious about it. I’m really excited to kind of just submit to the research. There’s this question often as a writer of, how much research is too much research? And my answer for this play is: I’m doing all the research, all of it. This is the time. Generationally, this is a crisis point and we can’t keep kicking the can down the road. Culturally, we need to get real about climate, now, and make big, hard, scalable changes. We have to give up a lot of comforts and conveniences. How are we going to make this happen? Because it needs to happen. So, I just want to contribute in the ways that I can to that conversation and base it on solid research.

Faith: With all of this, the concern with climate and the very real impacts that it’s having on people’s livelihoods, it makes complete sense to me that you would apply for The Next Forever. But why did you apply? Are there specific things at Princeton that you are [wanting] to dive into?

Kate: [At the] most basic level, it’s really helpful having support when you’re trying to do something ambitious. As I was starting to work on this play, I felt this wants to be big. Also, I personally am not independently wealthy and it really helps to be paid to do work.

And it really helps to feel the community side of it, to feel like there’s a theater company, and in this case, also a university that is invested in this project happening. I feel like, with all powers combined, I can realize this play at the level that I want to realize it. On the research front, I’m already deep into the research, and I’m actually teaching a course at MIT on climate representations in the media this fall. So, [I’m] currently re-prioritizing what research I need and want to do at Princeton. I’m actively engaged with that right now. I’m really excited that I will have a research assistant to help me organize the things that I’m working on. We’re still figuring out how to make this happen, but I’m also very eager to interact with students, especially as… It feels like there’s a certain danger in having one person put forward a vision of utopia, right? So, I’m really interested in having conversations with diverse members of the next generation around what is your idea of utopia? What actually sounds and looks and feels good to you? Being in contact with more minds than my own to imagine the future is a big part of what drew me to applying to this. I also really respect The Civilians.

Faith: It’s so true that utopia at best is a collective dream, as opposed to one person’s architectural project. Especially if we all have to live in it. I am really interested in what you’re saying about how this project wants to be ambitious and big, and it makes me want to ask, what does ambitious look like for you? Are there experimentations with form and language that you’re looking forward to? It seems like language is such a big part of your work and your practice.

Kate: Yes. I do think it’s gonna be ambitious on the level of form. And it just feels really important to me to actually know what I’m talking about, in a nuanced and detailed way. There’s been so many deeply intentional and powerful misinformation campaigns around climate coming from the fossil fuel companies and the political right for four plus decades now. I want to be writing from a deeply informed place and synthesizing an understanding of where the science actually is at. I have another play that I’m working on concurrently that has zero research so I don’t lose my mind, but with this subject matter, for this particular project, it’s important to me to not contribute to further misinformation or clichés around this subject.

Faith: What research have you done so far? Or is there anything that you have read that is really exciting to you right now?

Kate: I’m looking at the corner of my home office that has like, I don’t know, 35 books on the subject that I’ve been reading this summer. Okay, I’m just gonna pick one of these books. If you want a book recommendation, I recommend: Don’t even think about it: Why our brains are wired to ignore climate change by George Marshall. It’s kind of an amazing compendium of obstacles, psychological and cultural, to getting accurate climate messaging out into the world.

Faith: Okay, I think that this is my last question: what is making you feel hopeful these days?

Kate: Kamala Harris. Also, in my reading, I have been alternating one depressing book with one optimistic book. That’s my reading pattern. So, every other book, I’m really hopeful.

Faith: And then every other other book, it’s like, “Oh gosh, it’s over for us.”

Kate: More often it’s: “This is gonna get really bad if we let it.”

Faith: Wait, I have something else: what does really bad mean? I feel like my understanding of climate is perhaps more limited than it should be.

Kate: I will say, nobody knows the future and that is one of the things that does still give me hope. This is a science based on modeling. Climate scientists make predictions based on what will most likely happen if we continue the path that we’re going down, if we don’t make big changes to our carbon emissions and don’t transition off fossil fuels ASAP. There’s a range of likely outcomes for each possible degree of global warming. I do want to be really clear there’s scientific consensus around climate change. No one who is paying attention could conclude that global warming isn’t real or extremely serious or caused by humans. The key uncertainty is what will we do with this knowledge in the present.

How do you maintain a sense of humor and find moments of beauty in awful circumstances regardless?

Climate affects everything. Viable human habitat, the part of the globe that we’re able to inhabit, has the potential to shrink dramatically, which will leave to lead to mass human migrations, which leads to greater political instability. At the same time, we’re looking at mass animal migrations and even plant and tree migrations. Violence tends to go up when it’s hotter, the ability to concentrate goes down, test scores go down. Continuing down our current path probably means more wars, more food insecurity, more draughts, more hunger, more “sacrifice zones” where the health and lives of marginalized people get intentionally abandoned (as they currently are, for example, in “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana). We’re looking at the potential massive infrastructure failures, both physical and digital, as computers need to be kept cool to function… if you want a high-level overview of this kind of stuff, I recommend David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth, both the annotated article and the book. If this kind of reading spurs you into action rather than despair, have at it, though I know many people can feel paralyzed when we zoom out like that. It starts to get too big for your brain to hold.

What I’ll be trying to do in the play is tell this story in a granular and grounded way, looking at the hyperlocal effects of climate change in one very specific city. Looking at visceral experiences, like the experience of a main character with asthma trying to survive intense episodes of lowered air quality. Or looking at the fact that higher heat means more frequent miscarriages, so what’s being pregnant really like as this gets worse? What do you do when there’s a heat island effect in your city and there’s no shade at your bus stop for your commute? And: how do you maintain a sense of humor and find moments of beauty in awful circumstances regardless? I want to use storytelling to help people get this on the micro level, on the level that affects our ordinary day to day.

I won’t sugarcoat that the situation is dire and we are currently not doing remotely enough. Even so, part of the messaging that needs to get out there is that it’s not, “Either we do everything right or we lose everything,” it’s: “Everything we can do to move in the right direction is a win and could help save something worth saving for the next generations. Big changes and mass movements often start with small first steps.”

Faith: Do you think that there are things [we] can be doing that are accessible for people who are not necessarily climate activists?

Kate: I would recommend following Katharine Hayhoe on Substack. She’s one of our best climate communicators right now and often talks about everyday things you can do, such as talking more about climate change and strategies for doing so. We’re still at a “raising awareness” stage for so many people. If you own a house, make use of the tax credits you can get from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act to lower your household emissions and start electrifying everything. Whether you rent or own, you can put the effort into getting to know your neighbors, so you can take care of one another in the event of a disaster and collectively advocate for your needs on a local level. But I would say the absolute most important thing is to vote for climate-prioritizing leaders. We have to act at unprecedented speed and scale to get off fossil fuels, we can’t skip that part, the hardest part, we really can’t, and that has to involve our governments and policy-making at local, state, and national levels. The affordable alternative energy options are there; the political will is not. I’ll just be specific about it. Former President Trump said his day one priority, if he gets re-elected, is “Drill, baby, drill.” So number one right now is, we can’t let that happen. Also, write your representatives more often to express that this is a priority for you, that you’re a climate voter. Hold them accountable.

The stakes are really high, unfortunately. But there’s a lot of good that’s possible.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

The Next Forever is a partnership of The Civilians with Princeton University’s High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI) and Lewis Center for the Arts.