Rehearsals are fast approaching for The Civilians’ newest show, Sex Variants of 1941. To say that this day has been long-anticipated would be an understatement. Artistic Director Steve Cosson first came upon the book Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns in the 90s. Since then, there has been a 2014 Joe’s Pub concert, a Princeton class, a workshop at the Mercury Store, a PS21 Residency, a 2024 Joe’s Pub concert and finally, on November 14th of this year, the show will premiere at NYU’s Skirball Center.

Like all Civilians shows, Sex Variants of 1941 is a piece of investigative theatre. It combines archival research and verbatim material with music, theatricality, and what theorist Saidiya Hartman calls “critical fabulation” – the combining of the historical-archival with fiction in order to fill history’s gaps.

Critical fabulation, a term first coined in Hartman’s essay “Venus in Two Acts,” is more than a filling in, however; it is a problematizing of the filling in. As Hartman says, critical fabulation is “to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.” In the context of Sex Variants of 1941, critical fabulation is a means of grappling with the gaps left in in the archives both of this specific work and of queer and trans people.

Since the later 90s when the project was originally conceived, to the 2010s, to 2024, American culture has seen a great change//not change regarding attitudes on the queer and trans identity. Discourse is more public, but issues of legislature and medicalization more politically explosive. (As in the 1930s when the book was written, marginalized people are being scape-goated, “politicized” in the stead of larger, more dangerous social-economic and political failings.) It is this which intersects most explosively with Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns, which (devised as a strictly sociological study by lesbian reporter Jan Gay) ultimately sought harm-reduction via the medicalization and prevention (rather than criminalization) of the queer body. How do we come to grapple with the legacy of such a book in 2024? How do we think about the voices of the study’s 80 queer participants knowing all that remains of these anonymized lives is a medical study? And how do we come to tell the history of this artifact without sentimentalizing, absolving, or condemning its players?

In different ways, it is this fabulation with which myself, Jessica Mitrani and Attilio Rigotti have been tasked. I sat down with them recently to talk through Sex Variants, their work, and the ethics of historical imagining.

Excerpts from our conversation below:

***

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

James La Bella

I’d love to start with your names and what you’re doing on Sex Variants of 1941.

Jessica Mitrani

My name is Jessica Mitrani. I am a visual artist. I’ve been a bit of an interlocutor for Steve for conceiving the piece. I’ve been also doing, with Attilio, visuals.

Attilio Rigotti

Yeah, and I’m Attilio Rigotti. I’m a technologist, theater maker, and video game designer now with my MFA in my pocket. My role is associate projection designer. Really, it is a role both of creative support and creative collaboration with Jessica to construct the visuals and plan how those visuals happen.

Jessica (Co-Conceiver/Video & Projection Designer) has been involved with the project for several years now, joining Steve during Sex Variants’ residency at Princeton. I joined the team in the autumn of 2022, first as a dramaturg and then as co-writer. Attilio (Associate Video and Projection Designer) came on during the Chatham residency, which saw an increased emphasis on the visual elements of the show.

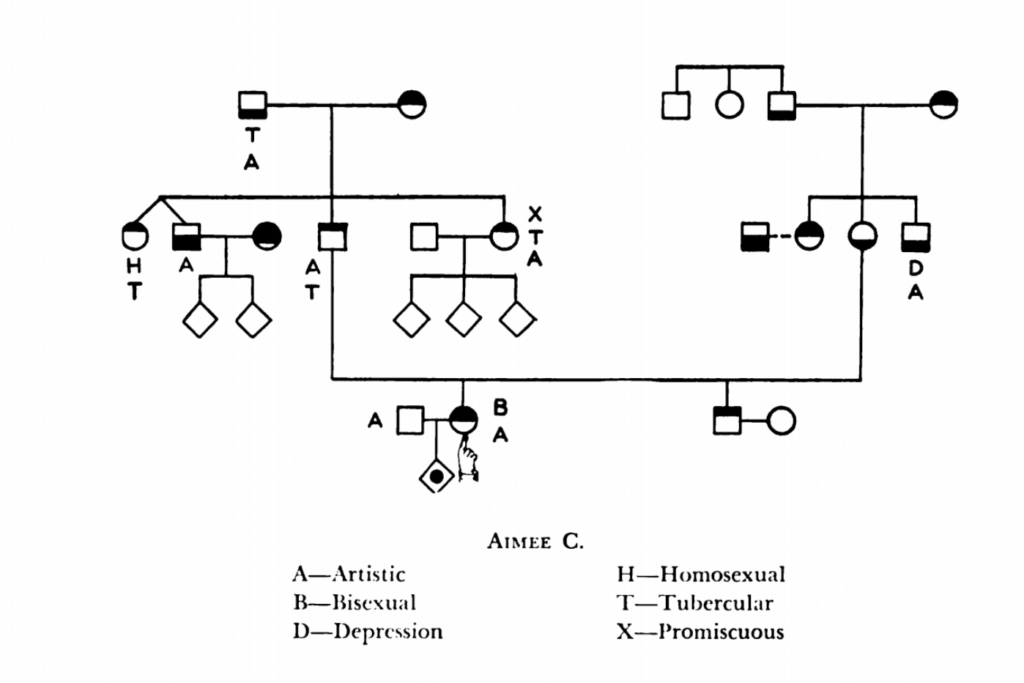

Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns is a book containing myriad visual components. Each of the 80 case studies include (along with a long-form verbatim interview) a genogram of familial deviancies, and diagrams from the medical examination. The appendix of the book contains x-rays, naked photos of participants, and numerous illustrations.

James La Bella

The illustrations in the book are a primary part of this artifact. I’d love to hear you talk a little bit about what they are. What kinds of illustrations are in Sex Variants?

Jessica Mitrani

Yeah. So, we have the illustrations of…well a few dildos, but mainly vaginas, breasts, and one particular image with the doctor’s fingers positioned around a vagina. We [also] have comparative nipples – like in sizes, widths, and textures. We have comparative vulvas – large vulvas, small vulvas, average vulvas, atypical sex variants’ vulvas. The doctors want to really insist in “what are the differences or the similarities” to try to find out if there’s any pathology or maladjustment. They’re black and white, and they’re beautiful and disturbing at the same time. That’s part of the appendix of the book.

Attilio Rigotti

I remember in our initial conversations what struck us was the sheer overwhelmingness of [the drawings] and how detailed they are and how artistic they want to be.

And that is very interesting-confusing-exciting-moving-complicated in contrast with what, I think, is a series of images that are way more abstract: these genealogy charts. [They are] all these abstract sorts of tracking down pathologies according to other types of deviancies in the genealogical tree.

And they’re both such a dehumanizing visual effect – one with the sheer amount of detail and the other one with the sheer abstraction of it all. I think we were always just shocked by that.

[An example of a Genogram in the book, from the case study of ‘Aimee C.’]

Jessica Mitrani

There’s something very calming I feel, unfortunately, about those charts. You have this geometry. Genograms. They’re still used today to map diseases and family connections and patterns. It’s all about patterns. So, the genograms in the book were used to really understand the homosexual as a pattern. And maybe, they’re trying to say, maybe [you’re homosexual] because you had a musical mother or like, you know, an alcoholic father. They have a tiny hand to point out where the subject is. It is really an opportunity to be quite playful in this geometry.

So, you have the genograms, you have the illustrations, and…I guess we might as well jump into these naked bodies. It took us a few attempts to get a volume that had the naked pictures. At the time, I guess, people were very excited to see naked pictures and they stole them. So, a lot of the volumes don’t have the actual naked photographs of the subjects.

Attilio Rigotti

I mean they are just so delightfully, beautifully confusing to me. Again, there’s a lot of them. There are some that are very medical, I would say, and then there’s a series of them that are posed with like…costumes? It’s this spectrum of how theatrical, artistic, aestheticized some of these images get. Right?

Jessica Mitrani

Totally. To protect the subjects, they blurred [their faces.] It’s pre-Photoshop so the blur feels quite ghostly and aggressive. So, you know, one of the conversations was “How do we present those images?”

When we were doing the workshop at Princeton, I collaged geometric figures on top of the bodies to kind of do a reduction of the reduction. It was an experiment. It was, for me, important to experiment. How can they come alive? How can we say “Okay, these are historical photographs?” Is there a way to approach this that is not diminishing? They’re questions that are not resolved, but they’re interesting.

‘Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns’ was printed in two editions. The first edition, printed in two volumes, contained the aforementioned naked photos. The second, in one volume, did not. The naked photos in the book are unlabeled and there is no key indicating which case study each body corresponds to. Within the archive, little has been found to explain this oddness – nor why some of the naked figures are posed with props and costumes.

James La Bella

That brings me to the next thing I want to talk about: All these images are of real people. The material deals with real histories. Everyone in the book was a real person. Something I’m grappling with and want to talk to you about (because I feel it’s a commonality our work shares) is: How do you narrativize the history of a marginalized people you don’t have comprehensive documentation of?

How are you grappling with that in your work? How are you tackling it? What are you curious about? What are you having problems with? I know it’s a conversation that’s pretty ongoing in this project.

Attilio Rigotti

I think what I find pretty remarkable [about] this piece and [about] a lot of the work of The Civilians do is the idea that the stuff we’re doing is a manifestation of the archive. I think what we’re really grappling with, in a way, is the archive and the artifact of this book.

Any time we narrativize it’s us being like “we’re trying to fill in these gaps that exist.” But I think it’s more a deconstruction of this book – of how it got made, of the minutes, of a lot of things. And I think that’s interesting, because then we are grappling with the stories but are also grappling with how people constructed history, how they constructed a scientific text. And I think you learn of these stories and these communities through how people spoke of them – both with the good and the bad. I mean we use a sort of lens that avoids, I think, appropriation or sentimentalization or too much, you know, fiction. It rather, sort of, talks constructing. It’s a little abstract, but it’s the idea of like…in understanding how knowledge is constructed, we understand ourselves.

Jessica Mitrani

And there are some anchors, right? Like, for example, there’s the burning of the Hirschfeld texts. I think we will take some images that are iconic and weave them in with these blurrings, with these reductions, with idea of the film negative that is both cinematic and medical.

That sort of textural palette – of an x-ray and the negative of the film – that’s where the fictionalized 1930s and the medical can intertwine. We want to make it visually appealing and also grounded in archival images and texts.

The Nazi burning of the Hirschfeld Library (one of first and largest libraries of material documenting queer life) is one of the most photographically recognizable book burnings from the era. It is at Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexology that Jan Gay learned of Hirschfeld’s psychobiological questionnaire, which she would adapt to be used for Sex Variants. By the time the study was published, most of the works that had inspired it were gone in smoke.

May 6, 1933 – the burning of the Hirschfeld Library.

James La Bella

Yeah, Attilio, I feel like it’s such a perfect encapsulation of this project to say that with this fictionalization, what we’re grappling with is the archive and the artifact of this specific book. Filling in those gaps is more of a grappling with absence than it is us trying to create a new story.

Early on, Steve had me read Heather Love’s amazing book Feeling Backwards and she says something in that introduction that I’ve thought a lot about with this project. She says that, specifically with queer history, we can’t rescue people from the past and we cannot seek rescue from people of the past. In engaging with these archives, we need to be finding a third way of being. That’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about.

How are you grappling with some of the abjection of this book? You talk about these nude photographs, these drawings of vaginas – what are you thinking about in terms of how to put them on stage?

Attilio Rigotti

It’s interesting how much of this project is this focusing on what’s absent. Like, where’s Jan Gay? What happened? What is that absence? Who are the people who all we have of them are their vaginas? Who are these people? You know, I think what Jessica always says so beautifully is that we’re trying to reframe them and highlight the beauty of them as much as [the doctors] were trying to not do that. It’s about somehow, in whatever we have, trying to capture these people. Right? Like, who was this person with that specific vulva? Who was this person who wore this fabric in a certain way? I feel that those people are trying to push through. And we’re trying to capture that.

Jessica Mitrani

I think once the script is tighter that will give us a north [star] of “What is it we want to show a little bit of…or not?” A lot of these things, even these illustrations, can be blown up, can be made almost like galaxies. So, there is a way to visually approach this material in a way that can be both literal and a little bit cosmic.

Attilio Rigotti

And that’s something you’ve always charged me with, Jessica.

Jessica Mitrani

And also, we think about how data – whether it’s text, numbers, measurements – can form a human being. You have all these landscapes, curves, charts, measurings, words, that constitute bodies. That’s an interesting material, how that text and those columns and charts can be used aesthetically to convey “All of this is supposed to articulate a human being and at the same time we know we’re more elusive than that.” So, I think that’s an interesting thing to play with…the concrete and the elusiveness of being.

Attilio Rigotti

I think we still are figuring out – I don’t know if the ethic is the right word – but “what does it convey to bring up those images and put them on a huge projection screen?” I don’t think we know. We’re trying to navigate that. And I think it’s something that a lot of people are navigating, even in archeology.

I’m thinking now of conversations around mummies. People being like “Should we be doing this? Like, aren’t we just showing the dead to everybody?” So, we are still navigating that. That’s part of the delicious complicatedness of the project.

James La Bella

Yeah, absolutely. There is such a complicatedness to this project. Something I’m thinking about is: We have all this data on these people, and we know they were real people, and there’s a chasm between those two things. And thinking…what do we do about that? What do we do about that chasm? How do we fictionalize it? I feel curious about that because I think whether we’re actively wanting to engage with that question or not, we are. Particularly with, I feel there has been a recent invigorative trend of reexamining history and digging out these figures that have maybe not received a lot of narrative representation. And what does it mean to represent these people?

Jessica Mitrani

[Earlier] you said the word “abjection.” But for me, part of what is really interesting about this is that there is a lot of…it’s not about joy, but so many of the personal stories are filled with this criticism of society and this rebelliousness and this “Why is homosexuality a problem? Why is it that that that society has to look at this like that?” Some people are very content with their personal choices, despite the challenges. An integral part is to recognize that even in this narrative where we don’t know many things, we can also see certain voices that are very contemporary. That’s nice. It’s not for me to be sentimental about, but I’m attached to that the same as I’m attached to the abjection.

I want to see people not judging with our knowledge and our vocabulary and also recognizing that in another time there were spirits that are contemporary. They could come right now and speak to us in the way they thought about family, the way they thought about society, the way they thought about capitalism.

Again, this thing is not about recuperating or saying, “Those doctors were evil.” The easiest thing would be for us to look out either in a totally derisive way or totally trying to uplift. I think both of those things are trap.

James La Bella

There are so many moments of the sublime in this book. And also, it’s amazing how contemporary-I mean, thinking about this decision Jan Gay made right at the beginning of the formation of the committee, which was the medical codification of identity as a means of harm reduction. Like, what is it to make that decision? And it’s one she made in the creating of this book and we see how it pans out and what happens.

You’re both great. I think something I’m super excited about, Jessica as you talk about galaxies, is the galaxy of people working on this play. Steve has been working on it since the 90s. We have work from Michael Friedman. We have the two of you. The amazing musicians Ada Westfall, Stephen Trask, Martha Redbone, Aaron Whitby. I think just as this book exists as a constellation of a bunch of different people coming together to make an artifact, so does the show Sex Variants of 1941. I don’t know. Is that trite? Is there anything left you’d like to say?

Attilio Rigotti

I’m just pumped. It’s such a delightful experiment. It’s an artistic experiment. And it’s the idea of capturing a human being, right? I think we, all of us, are trying to capture in every single aspect we can these people – we go visual, we go fictional, we go literal, we make songs – because human being are all those things. And somehow in between all those versions the truth exists.

Jessica Mitrani

What I love about this project is that, while it definitely was not what Jan Gay envisioned, it gives us an opportunity to demystify this idea that queerness or transness is a thing people are being brainwashed into. It’s historical texts like this that continue to counter the fear narrative that we encounter in today’s politics. It says, “No. This has existed since the first person.”

Sex Variants of 1941 runs November 14-24th at NYU’s Skirball Center.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

James La Bella (he/him) is a writer and performer from New England. He earned his BFA from Emerson College, with additional coursework completed at Harvard University. Jameslabella.com

View all posts