Jan Gay’s life defies easy categorization. Born Helen Reitman in 1902, Gay was the prolific interviewer and queer ethnologist whose research and connections made the Committee for the Study of Sex Variants possible. Despite this, she was erased from the study and received little to no credit for her work. In the following interview, I talk with Michael Waters–a writer and historian–about Gay’s role in shedding light on American queer communities, the perils of credentialism, and whether Gay would have liked Chappell Roan (short answer: yes).

**********

First question: what brought you to the work of Jan Gay? Was she someone that you’d always known about, or did her name just pop up somewhere?

I first found out about her through the work of Hugh Ryan, the historian who wrote When Brooklyn Was Queer. She’s mentioned on a couple of pages of that book. Hugh had always kind of told me that Jan Gay is someone he’s always wanted to look more into and hadn’t had the time. I was really interested in her because I think… One thing that fascinates me about queer history is the ways you can find queer community in these eras where you don’t necessarily expect it. Like, the 1930s when Jan Gay was doing her research was not a time of formal queer organizing or formalized queer organizations. But through studying Jan Gay, you see that she had this established network of queer people that she was working with, and she herself is doing research on and trying to make sense of queerness. [She thought if] we could tap into community knowledge, maybe we could legitimize ourselves in some way in the public consciousness. And so, I think what really drew me to her is that her work is driven by a desire to understand, but also it’s like community organizing in a way. There were a bunch of queer people in New York City, especially queer women in New York City, that Jan Gay knew, and a lot of her work is about tapping into, “How can we use this to some kind of political end?”

I’m really drawn to the fact that Jan Gay is a queer identified woman who is doing work on the queer community when so much of the history of medical research of queerness is awful. And especially from this era, non-queer people were the ones pathologizing and sensationalizing different aspects of the community. And, you know, with Jan Gay, there’s this element of reading between the lines, because we don’t actually know the full extent of what her research even said. So, to some extent, I’m extrapolating a little bit based off glimmers.

There are so many interesting avenues I want to explore in what you just said. One of the things coming to the forefront of my mind is this idea of finding community with queer figures from the past, and how that forces us to extrapolate and make assumptions because so much is lost to history. How do you approach those gaps as a researcher and as a writer? Balancing that tension between wanting to project our fantasies onto people, or wanting to project our dreams onto people that we feel a kinship with versus going, “Okay, this is what the archive says. And, I guess that’s what’s ‘true.’”

Yeah, I think that that is a difficult balance to strike. It’s really important to separate out what we know for sure versus, potentially, what is a little bit speculative. When you read Jan Gay’s letters, when you read the excerpts from her work, and the way that other people and other sexologists were talking about her work, I think you can read between the lines and guess at what she was trying to do. But I also think it’s important to acknowledge when you are reading between the lines a little bit. The reality is that for a lot of early queer figures like Jan Gay, and especially a queer woman in this era, there was no formalized attempt to save her records. Institutions didn’t see her work and her life story as valuable the way a lot of us see it today.

Ultimately, the work of the historian is piecing together a bunch of disparate sources, really, whatever you can find on her and trying to build as much of a picture as you can. But I think ultimately, to say why she matters requires just a little bit of reading between the lines and [hypothesizing], “It does seem like she was trying to do this.” And, you know, no one has found her missing book, so we can’t really know for sure, but I do think a little bit of speculation based on evidence, as long as it’s demarcated as such, is also meaningful.

How would you describe her life and work, in terms of what drove her and maybe what her dreams were? When you talk about how she gathered people to sort of legitimize queerness, it makes me wonder also if, in a way, she was also providing a community service for people to actually be able to speak about their experiences. The sheer number of interviews that she did begs the question: what would motivate somebody to talk to this many people and try to collect their stories at a time where it seems like… it wasn’t safe to openly admit that you were queer? I’m just curious to know if you got a sense of what drove her.

I think what you said about her doing a community service is interesting, and I think it’s certainly a strong possibility. I mean, she had access to this incredibly rich queer community in New York in an era in which [queer people] weren’t being talked about or acknowledged or written about in any kind of thoughtful public way. I think this is probably why she worked with Dr. Henry in the first place. There’s some usefulness to having nuanced accountings of queer community that can be used to change how scientists and psychiatrists were talking about queerness. I do wonder to what extent this was also a service for the community itself, to sort of show how varied the fabric of queer women’s experience in the 1930s. It’s hard to know what audience she saw for her book. But, I also think that it’s valuable for queer people themselves to be able to see the fabric of who we are, and the vast range of people and experiences and gender and sexual relationships that are possible.

I mean, it’s something that I think I have on the brain, that question of: when you are studying a marginalized group that you yourself are a part of in some way, who is it for? And is it extractive? Just trying to make sense of that, because I think what you brought up about audience is really valuable and interesting. Like, who was this research for initially?

That’s the kind of thing we could try to answer more clearly if we could read her book, ex., what is the language she’s using? What is the implied audience? How academic is it versus sort of public interest?

Did Jan Gay ever train as a sociologist, or was she kind of a street sociologist?

That’s a good question. I mean, it seems like her background is really linguistic. Her resume says she did language study in Mexico City, Paris, Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires throughout the 1920s and 30s. It does seem like she was mostly a writer who sort of took on the field of sociology in order to best articulate the work she wanted to do. I do know that she studied with Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin before she did her own study so she certainly had an exposure to academia.

There’s something very interesting to me about legitimization and… Her research not necessarily being considered legitimate because she didn’t have the right degrees. It seems like she had a wealth of experience in many things that are potentially more useful even than purely academic training. I don’t know if you have thoughts about that, i.e., how can we re-conceptualize what research is and who is allowed to do it?

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, that’s just an ongoing thing with the way academia is structured. Jan Gay was the foremost expert of lesbian life in America in the 1930s. No one was trying to take that throne. But she, by happenstance, probably spoke to more lesbian women in America during that period than anyone, and yet, her work and her knowledge is not considered legitimate until she’s working with this more experienced male academic who ultimately stymied her research and sensationalized it. And, I think an important story to think about in that time period, and then also today, is the way in which Jan Gay had every credential but a PhD in sociology or something like that, especially when we’re talking about people from marginalized communities telling their own community story.

I’m wondering now where her legacy lives on in that respect. I mean, now there’s so much queer theory and queer history, but I do feel like there are stories that that are still not being told. And, I just find myself hoping that as more people encounter her work, they will feel empowered to go into their communities and collect knowledge. With that, do you have a hope that of what people will take away from learning about Jan Gay and interacting with her work and her life?

I have two different takeaways. The historical takeaway my mind goes to first is that Jan Gay’s work shows us just how rich and sophisticated and sort of interlocking the queer community—and especially queer femme community—was in the 1930s. In the historical records, we really only see glimpses of this. When you’re doing queer history from this period, you’re looking at arrest records, you’re looking at court judgments, you’re looking at tabloid magazines that would have funny, sensationalized headlines about, “All these pansies in a club.” But you don’t really see, from a queer perspective, how this community is interlaced. And I think what we see from Jan Gaye’s work, the fact that she knew hundreds of women who have all kinds of different careers and backgrounds and sexual experiences… I think it shows us that we only know a tiny portion from what has been published recently. And I think I have a broader belief that we are only seeing fragments of what was a much more expansive and interesting queer community, especially pre-WWII. To my original point, this was an era when there weren’t gay organizations formally. There weren’t gay newspapers. But there is this ecosystem of queer life that was happening. And I think from what we see of Jan Gay, we can see how much more there is to uncover about that community and how queerness has changed. I think that’s one sort of historical takeaway.

And then I think I think your point is a really good one about how Jan Gay took it upon herself to say, “These are stories that matter, that I want to put into context, and I want to gather together to just show how wrong everyone else is about queerness.” If anything, her story tells us just how fragile sometimes these community stories are. And you know, when we’re living in it, it is really hard to remember how easily forgotten it might be later. Institutions are not going to document everything, and especially when we’re talking about certain marginalized communities or some kind of recurring space that potentially deserves its own documentation, that brings together a bunch of different people with meaningful experiences. And I do think that a lot of this stuff does get lost, but just because Jan Gay did the work that she did, even if it was never formally published, we are able to think much more expansively about lesbian life in the 1930s than we would have if she hadn’t. And I think there are always versions of that in the present too, of documentation work that any individual can just do to help remember and make sense of communities and organizations that they’re a part of. I hope people do that work for future historians too.

I think it’s important to break down the tools of research too, so that people can feel like, “Oh, okay, this isn’t so scary.” Like not only could they document their life and the life of the people in their community, but those stories are worth documenting. There’s also something about reading about Jan Gay’s path through life and all of the many jobs that she held. It feels like she lived a very queer life, a life that was not defined by trying to fit into any social norm or any defined path. She did whatever she felt she wanted or needed to do. And I feel like, as we’re in our late capitalist doom era, that lives like that are so rich and so valuable and worth knowing about so that people can feel less alone.

When I was reading about her life, there was a point, after the study took place and the credit was stolen, that she had… it seems like a mental breakdown? Do you get this sense that this was due to the trauma that she had experienced? I mean—and this is the sort of counterbalance to living this amazing life that involves moving around a lot… While all of that is really beautiful, I do imagine it takes a toll on you at a certain point. So, I was curious if there’s anything about her mental and emotional state after this study came out.

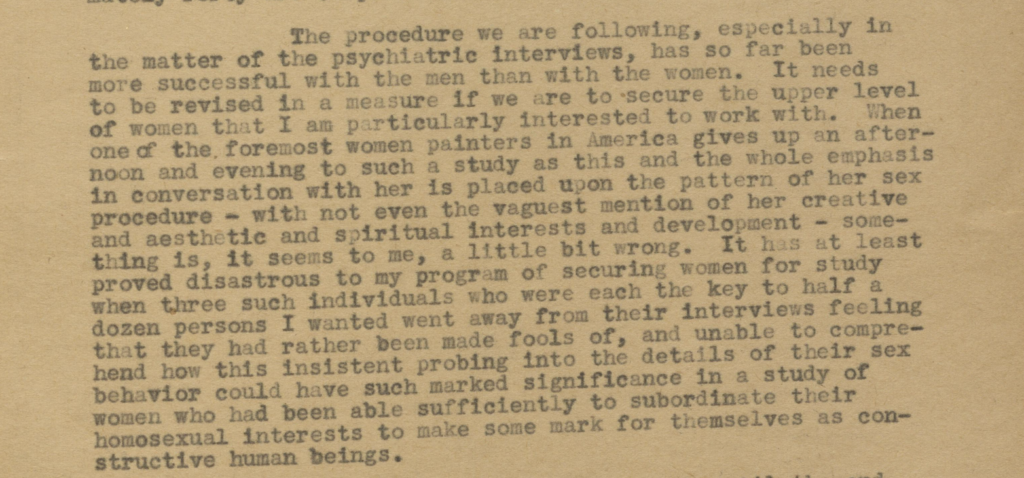

There’s this letter that she wrote the Sex Variants committee that is pretty scathing, considering it’s written to academics where there’s often this manufactured politeness, right? She was clearly incredibly hurt, not just by being written out of the book, but also by the ways she felt her research was being abused. As she says in the letter, she gathered together queer women from these different walks of life who had all these rich experiences, and the fact that the ultimate study that was published just attempted to pathologize them missed the entire point of the work. And I mean, this was over a decade of her life that she had spent working on this, and to have the research to be taken from her, then used to sensationalize her community is really devastating.

Ultimately, I don’t know what her mental state was. We just really don’t have many records of that. But when you map out her life, I mean, it is an incredibly resilient one and it is also one filled with trauma. From when she was born, her mom being put in this psych ward really early on, her dad abandoning her mom… she had a lot of personal trauma. I would imagine that that takes a really big psychic toll. But, it’s hard to know.

The late 1930s is when we see those traces of her fury at the Sex Variants committee. And then the other glimpse we get of her is when she’s living with Andy Warhol, which is in the late 1940s when she does seem to have been having some kind of psychic turmoil, like really intense psychic turmoil. It’s hard to know how much that was a one off versus how much that was a whole decade of experience. But I think certainly she went through a lot, and then she was mistreated and erased; it’s not the happiest ending to the story. I wish I knew more about what she was thinking and feeling in that time.

I suppose this might also lead us into the realm of speculation, but do you get a sense of her personality through the letters that she wrote? Does she seem like a fun person to hang out with? Would she like Chappell Roan? These are my very official academic questions.

I think she seems fun. She has such wild, varied interests. The fact that she was deep in the nudist movement, alongside researching lesbian life in New York… She was juggling a lot of different social worlds. I’m sure she was kind of a fun hang in the 1930s. I mean, she had so many friends, clearly… Many of the letters that were saved of hers are not personal, so I was seeing letters that she wrote to her agent, to the Sex Variants committee, to women’s colleges where she was asking about incidents of homosexuality. But even from the professional correspondence, you see this boldness and stubbornness simultaneously in her work, and in the way that she talked about her work. And you know, she’s getting some dismissive answers, but she’s also being really open about her questions. Those would have been somewhat controversial questions for a woman without a PhD to be asking at this time.

I wish I had her personal letters. I do think she would be a fun girl with great music taste, hitting the dance club. I imagine a sex researcher is probably at the club all the time.

Although sometimes, those people are the ones who are like, “I never go out and I’m gonna be nude at home.” You never can tell…

The last question I wanted to ask is about something you said earlier. You were talking about how our understanding of queerness and queer life has changed since the 1930s (I would assume, for the better), but I’m curious about some of those shifts that you’ve seen. What has changed? And what is your assessment of where we are now #InTheseTimes?

First of all, in the 1930s, Jan Gay was working with a really different set of understandings about sexuality and what we would call gender today. The concept of homosexuality was very much a conflation of gender; there’s this idea of a third sex as being an amalgamation of these identities that we have now separated out. And I think it’s interesting always to study the queer past, because I also think you see familiar questions and familiar ways of being that are categorized and classified and talked about fundamentally differently. I don’t necessarily think there’s a better or worse way to talk about these things.

Also, obviously, in the era in which she was working, it was nearly impossible to get research published about queerness that would have been very sympathetic to queer people. This was an era in which there’s was censorship of the mail. Overly positive writings about homosexuality could be demarcated as obscene and be confiscated by post office inspectors, which is why a lot of writings about queerness are in these tabloids that are taking a winking, sort of negative stance, being like, “Stay away from this club because it’s marauded by these homosexuals!” Certainly, at the other end of that, gay people are reading this and thinking, “Oh, I have to go there!” To even write about queerness in that era, you have to do some linguistic trickery. So obviously, there’s not the same level of that institutional resistance. But honestly, there’s some lessons from Jan Gay’s experience of queerness from the 1930s that we can apply to today, which is this idea of academia publishing these really sensational accounts of queer life.

What went wrong with Jan Gay’s research is that there was this deferral to male academic authority. And I think similarly today, especially when we see newspapers publishing about trans healthcare and trans kids, you see the same deference to academic “authorities” who don’t necessarily have much experience in the community or are not of the community. And a lot of the more localized, grassroots community-based research and experience is not taken as seriously. Direct testimony from queer people, and especially trans people, is not taken as seriously as a PhD who might have their own agenda, but might couch their analysis of trans childhood in the language of science and academia. And so, I do think there is a broader lesson here that we still need to learn of valuing different forms of knowledge making and knowledge production, especially when it comes to queer people making sense of their own communities that are all around them, versus always trusting the most credentialed person in the room, because they all have their own agenda too.

Today, Jan Gay probably could publish her study. But I still think that there is that same kind of headwind of prioritizing scientific and academic authority over the people who are actually affected and harmed by different policies. I think we’re still fighting that battle.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

Faith Zamblé is a writer, culture worker, and artist at large, originally from Waukegan, IL.

View all posts