Seeing a queer immersive Romeo and Juliet in a Bushwick club was not on my bingo card for March 2025. Seeing said club filled with invested–albeit bemused–audience members, on a Thursday night no less, was equally shocking. For all the hand wringing about the state of the American theater, this recent experience revealed to me that while the non-profit theater model may be in jeopardy, theater itself—as a feeling, as an artistic phenomenon—is not. Perhaps, it simply needs a location shift.

Ergo: the club.

I am not convinced that the club itself is the answer. There are certain politics of nightlife that can make it tenuous, dangerous, ableist, or downright unpleasant. The crush of sweaty substance-d bodies, the dark rooms, the late hours, the beauty politics: there’s a reason Pentheus didn’t like Dionysius. There’s a reason Donna Tartt’s novel The Secret Histories must end in misery and chaos once its characters partake in a Bacchic ritual. Losing oneself to the Great Unknown never goes well. However, the opposing Apollonian axis can, if unchecked, lead to a calcification of spirit, a worship of order and unity that starts to ring false in a 21st century globalized world. Therefore, club as physical location or as a site where specific feelings occur is closer to what I hope to explore here.

Philosopher, historian and bathhouse denizen Michel Foucault wrote in “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias”:

We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed. We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.

His words ring especially true in the age of the internet where our past selves and the selves of others continents away constantly confront us. We live in a rhizomatic world, not one of fixed temporal lines. Foucault goes on to suggest that the primary existential tension of the 20th century is therefore between the “pious descendants of time and the determined inhabitants of space.” I read this as a tension between narrative and experience, between thinking and feeling, between the institutional and the organic. But what does all this mean for us now? And what does it mean specifically for the theater?

My theory is that Foucault’s assessment of the 20th century still applies to us in the 21st, especially those of us committed to the practice of telling stories. Theater, which should reflect the times—chaotic times, unstructured times, unstable times—is instead clinging to narrative, proscenium and what has worked in the past. This isn’t to say that no one is breaking the mold, but considering the moment we’re living in, it’s surprising that there isn’t more theater in bars, more theater at the club, more theater that lives outside the limits of so-called respectability or immediate clarity. With questions around funding swirling in the air, partnering with community spaces seems not just logical, but formally meaningful, and an assertion of solidarity with the underground.

Spaces that celebrate the “fugitivity” madison moore writes about in “DARK ROOM. Sleaze and the Queer Archive,” eschew mandated veneers of decency, revealing something true and potent about society. moore quotes writers/theatermakers Alyson Campbell and Stephen Farrier who suggest that “queer dramaturgy [. . .] is fundamentally connected to performance that is often hived off from literary traditions in theatre.” They note that “much queer performance takes place in other spaces like cabarets or nightclubs,” but that these spaces are seen as the “poor cousin” of literary minded performances. With this in mind, what I am arguing for, and what I am seeing a push towards—especially in the wake of work like Anne Imhof’s DOOM: House of Hope—is a celebration of performance that spills outside of fixed, literary, dare we say, straight theater.

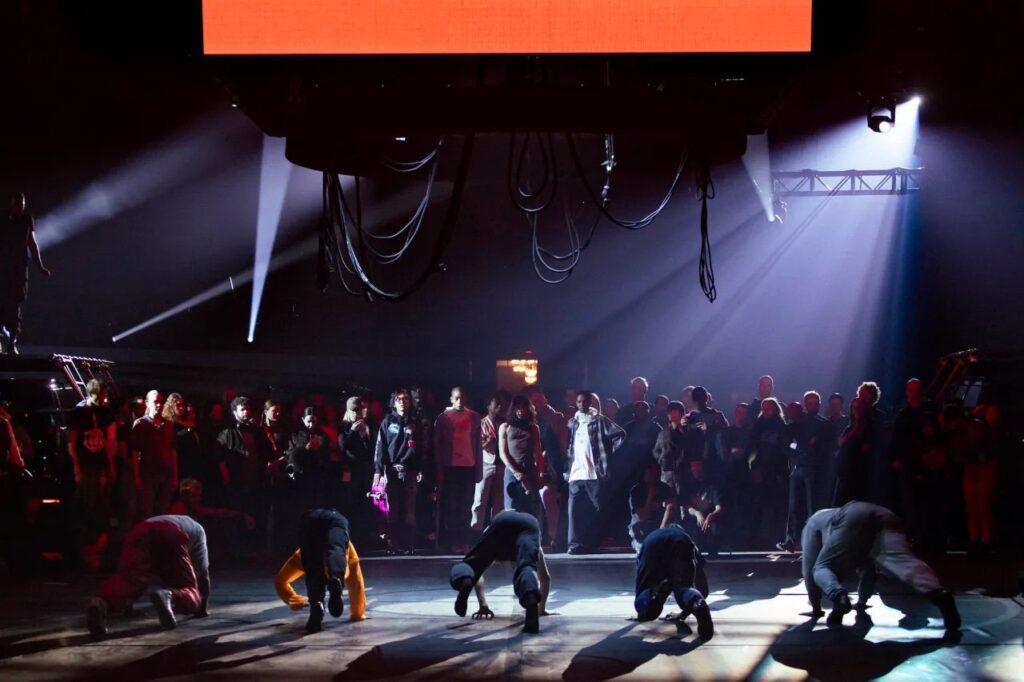

DOOM: House of Hope, Imhof’s commissioned takeover of Park Avenue Armory, featured, among other notable bits and bobs: bored looking models on their phones, a giant countdown clock, harsh industrial anti-rhythms, and dance of all stripes. Though I was not present for these performances, the reviews hint that the unwieldy nature of the drill hall became a feedback loop for Imof’s unwieldy, and occasionally (often?) unclear, ideas. As a lover of big ideas that don’t always land, I won’t feign objectivity in saying that there’s something valuable in being a little defeated by a space. And alhough the Armory is not a club, Imhof’s work is operating at the same temperature as club life, vacillating between red hot chaos and cool detachment, ultimately creating an experience that feels large in scope, spatially and emotionally.

The queer Romeo and Juliet I saw last week did not create a big experience, nor was it grappling with big questions. It was immersion on a small scale and generally struggled to find its center. It had, as the kids say, lost the plot, and not in a good way. Even so, attempting something large enough to hold the many mysteries of this moment was commendable and a reminder that even when it feels like we may have lost the plot as artists and citizens, there are always new ones to be found.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

Faith Zamblé is a writer, culture worker, and artist at large, originally from Waukegan, IL.

View all posts