Hello! Welcome back to this series of essays on eco-dramaturgy. In this episode, I pick-up the question of how theater might help us re-think the assumptions that underpin mainstream white environmentalism, this time by taking a deep dive in the historical waters of Eco-Theater. Before we dismiss this history as boring or unhelpful (after all, the climate did get worse despite all these plays getting made) I want to make the case for the usefulness of looking at what came before. It can be tediously detailed work, proven by the fact that this essay is the longest of the series, but it can also help us make sense of a field –eco-theater– whose entire task is to make sense of what’s happening to various groups of people contained in “us”.

In my previous essay I argued that Eco-Theater shouldn’t be a megaphone: to treat audiences as the recipients of loud and simple messages is too blunt an approach. I also argued our primary duty as artists isn’t to raise awareness: theater is more than a medium of communication. And I also argued that as theater artists we should not assume that “we” don’t know how to deal with the crisis: to make theater from that assumption erases all of the communities that have experienced environmental devastation for centuries. The task at hand is to think what Eco-Theater can be and I think a good place to start that process of imagining is to look at what Eco-Theater has been.

And so, I turn to think with the Eco-Theater of yore. The perspective I take with me is one offered by the One and Only Suzan-Lori Parks. In her essay Tradition and the Individual Talent, Parks argues that there are three traditions at work inside of us theater-making people: The Great Tradition, The Personal Tradition, and The Next New Thing. She argues that all three help and hinder our making, but that they all deserve our attention.

Here, I try to unpack a few Great Traditions of Eco-Theater in an effort to help us map the challenges of making the Next New Thing for Eco-theater. Hopefully, they can inspire you to reflect on your Personal Tradition. I offer them to you less like a guide and more like a menu: which ones do you like and why? What would happen if you tried the ones you haven’t tried before? What might we discover?

The River of Eco-Theater

I think that an easy way to conceptualize The Great Traditions of Eco-Theater is as a river. Rather than some sentimental “let’s-preserve-nature-for-recreation” reason, I like to think of Eco-Theater as a river because rivers leave a mark that is hard to see and understand over time, but it is there nonetheless. Rivers change shape over periods of time so long that we can’t see those changes, but they happen nonetheless. Because of these long-term dynamic changes, a river is essentially a process that leaves physical marks on the world.

Generally speaking, we can identify at least three parts in rivers: tributaries (flows of water that unite or contribute to a broader river like the many tributaries of the Rio Grande), a riparian meander (the winding flow of a river that can change shape over time but tends to remain on a single place, as illustrated in these gorgeous maps of the Mississippi River by Harold Fiske) and distributaries (places where the river breaks into smaller streams as it does in the Deltas of the Ganges, the Amazon, or the Nile).

If I had to describe Eco-Theater as a river, I would say it has at least four tributaries, at least 15 contemporary distributaries, and a wide riparian meander of practice/research/development. Normally I like to play with linearity (because linearity is so often colonial and normative) but in this case, it’s less confusing. So today, we will start at the beginning and go to the tributaries! These are plays (mostly) from before 2000.

For cultural and environmental reasons, the new millennium feels like a good point to break from “the long past” to the “recent” past. Most of these plays are from before 2000, but two are not: Métis playwright Marie Clements’ Burning Vision (2003) and the musical by Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis (2001). These are both important and influential for my purposes, so I place them as tributaries. Feel free to disagree. Without further ado, let’s go to some beginnings!

Starting with the local: The Grassroots Tributary

Writing for American Theater in 1992, Lynn Jacobson set out on a mission to discover a “green” theater across the United States in what she called “Operation Theatre and Compost”. The artistic choices she encountered blend themes and messages –”plays dealing with some aspect of our failing ecosystem”– with a macro dramaturgy of place – “productions grounded in a specific landscape or locale”. Her task was to try to articulate what Eco-Theater was being made across the U.S. and to share that with the readers of American Theatre.

The plays Jacobson found invariably encounter a dramaturgical tension: one between the material realities of environmental issues (cancerous waters, logged forests), and desires that conflict with those material realities (a desire for clean waters and for pristine forests but also the desire for economic development from industries that pollute and log). The conflict between environmental issues and local industrial activity is evident in all three productions Jacobson profiles: In Lowell, MA, Merrimack Rep stages an An Enemy of the People in a town with a history of polluted rivers; in New Orleans, LA, the Center for Contemporary Arts adapts Heiner Müller’s Despoiled Shore/Medeamaterial/Landscape with Argonauts to reflect the plight of the Black residents of Cancer Alley; and in Blue Lake, CA, the Dell’Arte Players’s Redwood Curtain Trilogy: The Scar Tissue Mysteries, was staged against the backdrop of logging and overfishing.

All three productions pursue the dramaturgical purpose of making eco-theater as a means to “do something” about a highly localized environmental issue, although two of these belong to the next tributary, the Grandaddies. Because their audiences are implicated by virtue of living in the places where environmental injustice is happening, the violence of representing environmental injustice is infused with the (already very messy) ethical considerations of representing a town back to itself.

This challenge is not palatable to all artistic leaders. For example, the artistic director of Merrimack Rep chooses allusion: he eschewed the decision to make Enemy explicitly about the Merrimack River, instead setting it in a vague New England town. Likewise in Louisiana, director Julie Hebert wondered whether the play may just remind the audiences of the plight they face as it happened in New Orleans. Jacobson captures this dilemma quite well:

So although it’s easy for theatre professionals and other outside activists to condemn what’s going on, the people who live there “have a very difficult choice to make: Is my son going to go without food today, or is he going to die of cancer when he’s 18?” [play director] Julie Hebert knows firsthand about difficult choices: Her father works for one of Louisiana’s oil companies; both her mother and aunt have had cancer.

This tension between preservation and economy is a defining feature of the Grassroots tributary of Eco-Theater. As they pursue the dramaturgical goal of “doing something” and they pursue it through locally-rooted productions, they rehearse the activist purpose of “raising awareness” while also anticipating the difficult aftermaths of raising awareness: anxiety, anger, fear, but also hope, energy, and enthusiasm.

Crucially, none of the plays or productions in this tributary have entered any kind of theatrical or literary canon. They also are part of a group that’s hard to study or encounter. Because of the artistic and scholarly bias against taking “community” theater seriously, the works are rarely archived or studied, so I imagine these likely serve as tentpoles for what is a much bigger group of plays that were not archived.

Stylistically, plays in this tributary tend to use very DIY aesthetics, summed up in the mid-90s by theater artists/scholar Downing Cless:

“Rough Style” (or low production values), “Episodic Structure” (or breaking the unity of time to cover as much exposition as possible), “Audience Contact” (or implicating the audience directly), “Documentary References” (or referencing actual statistics or stories about the issues they’re about) and “Activist Protagonists” (or stories built around people actively trying to change the environmental issues).

Here’s a synopsis for an unwritten play –let’s call it POWER & THE PEOPLE– that might come from this tributary. It is about the ice storms in Austin, TX in 2021 and 2023: ‘In the aftermath of Winter Storm Uri, and the dozens of Austinites who were left without electricity, gas, water and food, a young graduate student organizes citizens to create legislation that would require winterization of the Texan electric grid. The play is composed of vignettes from the 16th of February, March, April, May, and June of 2021, focusing on how long and delayed the access to service was in the wake of Winter Storm Uri. At the end of the play, the audience is invited to brainstorm which representatives need to be reached out to or voted out for the policy to take place. The snow is represented with packing peanuts and shredded paper, and the play is staged in the round with minimum costumes. It uses (unauthorized) playbacks of pop culture songs about snow in between scenes.’

With this example, I hope to demonstrate the dramaturgical agreement that these kinds of plays create. To be clear, I don’t think these plays are “bad”. They achieve an important purpose in bringing together different real times, peoples, and places – a key task in trying to make sense of a problem that is diffuse in space and time, like climate change. These plays and their makers recognize how difficult it is to make meaning about environmental issues by taking an individual or micro-perspective. They can, however, run into the ethical issues described above –“am I traumatizing my neighbors by making a play about an issue that was traumatic and deadly?”, and therefore the change they want to perform may be impacted by this re-traumatization.

In doing so, this tributary of eco-theater performs and embodies the work of many (largely white) environmental thinkers –Rachel Carson, Bill McKibben– that shaped the modern environmental movement. However, by adopting the environmental ethos of “doing something” that is rooted in Morton’s “ecological information dump”, many of these plays focus on education, exposition, and (perhaps most crucially) an attempt to shape their audience’s minds. Although they are influenced by explicitly political elements like Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed, they do not always* critically encounter environmental injustice or re-compose it for their audiences, and in foregoing the importance of aesthetics, sometimes they lack the dramaturgical reflexivity to think about the audience experience.

*I have not seen or heard all these plays, so take this statement with a grain of salt.

I would begin a list of plays in this tributary by including:

Seattle Public Theater’s Timber (1991)

The Ukiah Player’s Theater upROOTED (1991), and ReROOTED (1994)

Dell’Arte Players’ Redwood Curtain Trilogy: Intrigue at Ah-Pah (1979), The Road Not Taken (1984), Fear of Falling (1991)

The OTESHA Project’s A Reason To Dream (2003)

Kalamu ya Salaam’s The Breath of Life (1993), and

Martha Boesing’s Standing on Fishes (1991)

The structures of attention championed by these works are all rooted in a transparent dramaturgical intent to address an issue. Their key verbs are documenting, an attempt to influence their audience, and an emphasis on audience political participation after the performance.

These plays have had productions by various theaters, but they do not form part of a canon of U.S. theater that is presented in LORT regional theaters, or taught commonly in U.S. drama courses. So they are an interesting corollary to the prestige of the global western dramas that we will look at next. Crucially, I imagine these plays can (again, I haven’t seen them all) embody the Artist As Megaphone model. In some ways, it makes sense, right? Megaphones are often used in grassroots protests. If you are making one of these, how might you use fresh dramaturgical structures? How might you play on the fact that your audience expects your play to behave like these Grassroots plays and use that in your favor?

A Global view: the “Granddaddy” Tributary

In the latter part of her article, Jacobson wrote about the beginnings of an Eco-Canon, and listed several plays that I included in the list above. But she said all of them pale in comparison to the “granddaddy” of all Eco-plays: Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People.

I pick up that name to designate several plays – many of them written by white men of whatever we mean by “the West”– that were written long, long ago. In fact, many of these plays preceded environmentalism as we know it today, but over the 20th and 21st-century theaters have produced them with an environmentalist ethos. Scholars, too, have used them to think about the relationship between theater and ecology: since the mid-90s various theater theorists have located an environmental ethos in these canonical dramas, helping establish the academic field of Performance & Ecology. The Western canon has power, including the power to legitimize an area of study or practice that otherwise already existed independently.

These plays are not issue-driven. Consider Enemy, even though the dramatic tension is fueled by the pollution of waters of Stockmann’s town, unlike the Grassroots tributary, the play does not place tension on the protagonist or audience to “fix” or clean the waters.

Because of how the environmental “issues” function in these plays, an interesting dramaturgical question arises when we compare both the Grassroots and Granddaddy tributary. What, exactly, counts as an eco-play? Does it have to have some kind of environmental degradation as the central conflict (as Enemy) or as background (as in The Cherry Orchard)? Does it have to involve a natural disaster (as The Tempest)? Does it have to be a drama? Or can it be funny like Aristophanes’ The Birds?

I would begin a list of plays in this tributary including:

Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (1882)

Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya (1887) and The Cherry Orchard (1903)

Aristophanes’ The Birds (414 B.C.E)

William Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1610-11)

Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days (1961)

If I had to characterize these plays as a set (again, I have not seen productions of all of them), I would say they create dramatic conflict with varying degrees of relationship to environmental issues. Because they are sometimes obliquely environmental, they don’t necessarily point to a solution to an environmental issue as we understand it today, but they can help audiences make meaning about the relationship between (some) humans and the natural environment.

How? This is where context is key!

For example, The Tempest is set in the aftermath of a great storm, and was written at a time when it was commonly believed that the damaging cold and wet conditions prevailing during the Little Ice Age were man-made and the product of witchcraft. At the end of that play the colonizer protagonist Prospero, who appropriated “native” magic to cause the play’s titular storm in revenge, renounces his powers and asks to be set free. So maybe the play back then was an instigation to not mess with the weather if you were a water witch? But the play now can help us to think about the impact of knowledge and technology over the natural world. I also want to caveat that unlike many of the other authors in this essay, we can’t know or ask them whether their intentions were or were not “environmental”. All we can do is use what they left behind to make sense of the mess we live in.

Might there be something in between the Grassroots and the Granddaddies? And where are the other women and other people of color theater-makers? Perhaps there is something that is just as committed to the craft of theater-making as an artform as it is to responding to a specific political issue affecting the playwright’s community?

I think so. And those are the plays I group under what I call the Global Majority Tributary.

This is a group of eco-plays that, like the “Grandaddies”, may not have been written as eco-plays as we would understand today, but their dramaturgical impetus certainly includes environmental issues because they affect the communities that the playwrights belong to. Aesthetically, these plays are quite divergent from each other –in some ways I am centering a white patriarchal gaze by grouping them all together– but I could not figure out a different way to group them given that I am not as deeply versed in the broader canons of these plays as I would like to be.

These are plays written about issues that affect specific communities by virtue of their identities or geographies. They uphold the plight of those specific communities, while experimenting with theatrical conventions and use those conventions themselves to constitute specific relationships to the audiences. If the Grassroots plays imagine their audiences to be potential activists, and the Grandaddy plays imagine them as maybe attending the play for the environmental issues or maybe attending them as entertainment, the Global Majority tributary imagines its audiences as capable of adopting the perspective (racialized, gendered, postcolonial, or otherwise) of a group of people under many kinds of duress, which include environmental duress. If the Grassroots plays try to mobilize activism, and the Granddaddy plays try to offer meaning-making opportunities, the Global Majority plays are an act of resistance against the systems that create environmental issues alongside racism, sexism, and colonization by mobilizing the perspective and voices of those most affected.

Because these playwrights mediate many kinds of oppression, many experimental theatrical forms, and far from uniform audiences, they practice micro- and macro-dramaturgical precision. Like some Grassroots tributary plays, they understand that the play’s dramaturgy and its dramaturgical mechanics have to align, but they go beyond raising awareness because they don’t assume their audiences are ignorant about the issues. All of this is a round-about way of saying that this tributary practices aligning its dramaturgical choices and its political purposes. Their choice of narrative structure, character composition, and “environments” are aesthetic as much as they are political. And in aligning aesthetics with politics, the key verb for this tributary is the re-articulation environmental issues from culturally and geographically-specific points of view.

In this group, I would include:

José Rivera’s Marisol (1992)

Cherríe Moraga’s Heroes and Saints (1992),

Teatro Nuestro’s La Quinceañera (1990);

Marie Clements’ Burning Vision (2003 )

Coatlicue Las Colorado’s Open Wounds on Tlalteuctly (1994)

Wole Soyinka’s The Swamp Dwellers (1958)

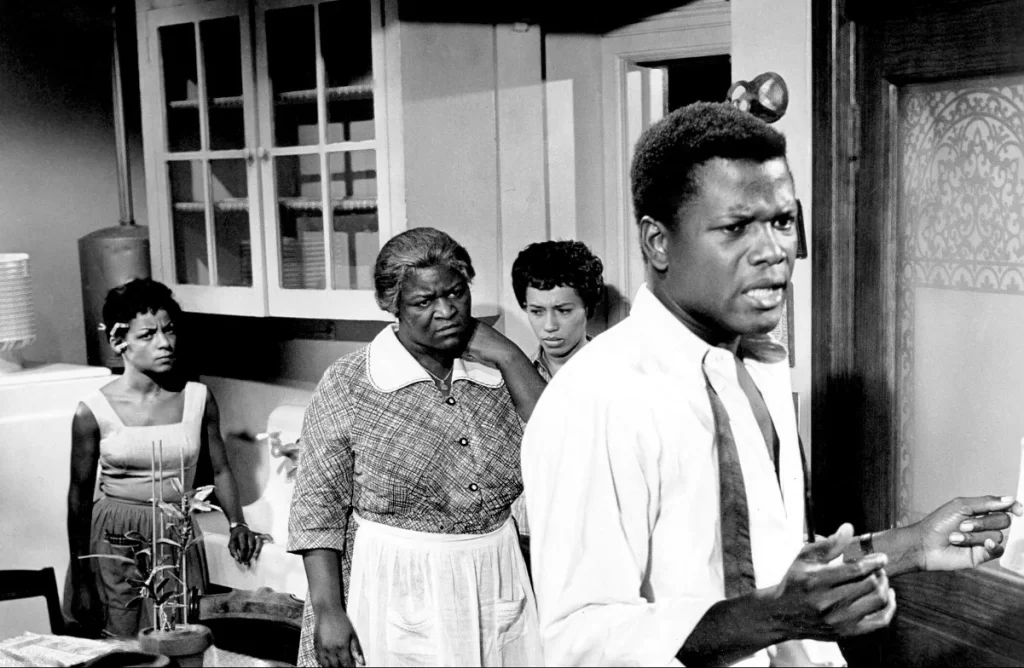

Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (1959)and What Use are Flowers (1972)

Caryl Churchill’s Fen (1983), and Far Away (2000)

There is much to unpack by contrasting any one of these plays to the other ones, which would take me too long to do here. However, there are dramaturgical questions we can unspool by considering the Global Majority tributary alongside the Grassroots and the Grandaddies: what role do a playwright’s identity and positionality play in influencing how they/we tell environmental stories? What if we subjected the relevance of the messages in the Grandaddy tributary (often deemed universal) to the same scrutiny that we subject Global Majority playwrights? Or vice-versa? How might eco-theater contend with the histories of conservation and environmentalism (at least in the English-speaking Global North) that cater to a white gaze?

From that alignment between dramaturgy and politics, I use this tributary in the river of eco-theater to locate a reflexivity that will serve us downriver and in my next essay. This reflexivity indicates an awareness of place, people, and practice and how they intermingle with each other. Of this group, Burning Vision is perhaps the piece most studied in academia (studied by a whopping 12 peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, and many more essays), because the play’s purpose of resisting extraction is embodied through the play’s dramaturgy, not only in its story. In fact, the concept of eco-dramaturgy, which I will explain in more detail in the next essay, was coined by white scholar Theresa May while she directed that play.

Having established some interesting questions and briefly sketched the inter-relatedness of place, people, and practice in a process of Eco-Theater, I now turn to the wildcard: the The Musical Tributary.

This is perhaps the least-known, least-studied tributary of Eco-Theater. But in its difference may lie its ability to be effective to help re-think environmentalism. The works in this tributary account for affect, not just thought, as a way to engage audiences and think with them. Both plays and musicals tend to an audience’s emotional experience, but perhaps musicals as a genre more happily embrace their role as form of entertainment. Its key verb is to pleasure and entertain as they create stories that embrace their constructed and subjective nature. They may contain political messages, but they are also made to be enjoyed: sung along, danced to, felt with. In this adoption of emotions and feelings alongside thought and sensorial experiences, musicals can help audiences understand the contradictions in environmental issues and –crucially– embody or release those contradictions through song or laughter. It is hard to make a genreal statement for how these musicals imagine their audiences, but I think it is fair to say the makers in this tributary do not ignore sense of humor, and the audience’s capacity to listen and participate collectively without implicating them in a specific political action.

A good example is the musical Urinetown. I raise eyebrows when I consider it a piece of “Eco-Theater”, but it feels just as environmental as The Tempest, or Uncle Vanya. It is set in the aftermath of a drought that leaves water in the control of a private company. The musical is satire, but it contains an environmental problem –drought and water management– while critiquing an approach –overzealous and profiteering water privatization– while perhaps suggesting some kind of management is necessary. All of these ideas could be explored in a drama –we will take a closer look at British Climate Dramas in the next entry– but Urinetown uses laughter and dramatic irony, and in that allows its audiences to take pleasure in this intellectual debate.

Many of the other Eco-Theater musicals are lost to time and have not been archived, so I can’t divine too many other dramaturgical interpretations. But perhaps the very fact that musicals are not the form we first think of when we think of Eco-plays carries insight. The fact that musicals are questioned for their effectiveness in environmental issues, maybe says that we’ve unconsciously assumed that an Eco-Play is supposed to be a certain way. Serious (as opposed to emotional), real (as opposed to stylized), and factual (as opposed to fictional). The dramaturgical question becomes, what if we write a piece of Eco-Theater that is emotional, stylized and fictional? Could that still be effective?

This is where a contemporary play like Anne Washburn and Michael Friedman’s Mr. Burns, A Post-Electric Play is interesting. It’s completely fictional, and does very little in the way of explaining to us what happened in this fictional future world. It draws attention to the nature of its composition, and I would argue highly emotional and stylized –especially the 3rd act.

Other examples of plays, musicals and cabarets in this tributary include:

Don Richard’s and Thomas Vincent Cantor’s The Soul of Sequoia: The Forest Play (1919)

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma (1943) (… think about it, who belongs to the land? And who does the land belong to?)

The 21st Century Radio Hour, or Atlantis Calling, presented by Seven Stages (1991)

Ryan Cheyney’s La Boda, featuring the group Sandunga (1989)

Water Theater’s Eco-RAP (1991)

Underground Railway Theater’s The Cristopher Columbus Follies: An Eco-Cabaret (1992) and InTOXICating: An Eco-Cabaret (1994)

Conclusion: Cliff Hanger

I will end here briefly by, once again, hoping that the broad overviews I have provided above help you situate yourself among this Great Tradition. I don’t have a great conclusion, yet, because there is a bit of more contemporary context to look at, which I take up in the next essay. We will spend some time untangling the many distributaries, and offering a brief overview of the riparian meander of Eco-Theater, to continue re-thinking Environmental Justice from the perspective of the theater.

Also, if you want to read more about these tributaries, look up the work of Downing Cless, in particular his book Ecology and Environment in European Drama (2010), and Theresa May’s book Earth Matters Onstage: Ecology and Environment in American Theater (2020), as well as the very accessible volume 100 Plays To Save The World (2023), by Elizabeth Freestone and Jeanie O’Hare. The 2nd edition of 100 plays has a foreword by Annalisa Dias and Tara Moses which is *chef’s kiss*. I used all three of these books, plus my own research and practice to assemble these categories.

***If you’re curious to read more about how other people have thought about Eco-Theater, I sat down to catalog at least 100 peer-reviewed sources, 100 HowlRound essays and over 100 productions, all of them are listed in this fairly messy database. I have identified just under 50 terms, but I will return to why I stuck with Eco-Theater and Eco-dramaturgy in the next essay. Until next time. And feel free to contact me through my website or IG if you have thoughts about any of these ideas!

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

Khristián Méndez Aguirre (he/él) is an artist/scholar working at the intersection of Latino performance and environmental justice.