Is This A Room stages a taut 70-minute conversation based on the declassified transcript of the FBI interrogation of Reality Winner, a former intelligence specialist currently imprisoned under the Espionage Act for leaking information about Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. Created by the downtown theater company Half Straddle, known for its “focus on feminist and queer dynamics” in shows like In the Pony Palace/FOOTBALL, a play about football and cheerleading performed by a female and transgender cast, and Seagull (Thinking of you), a deconstruction of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, Is This A Room is both an urgent, drawn-from-the-headlines show about whistleblowing and an acutely-observed portrait of a woman whose life is changing permanently in front of an audience’s eyes. As theater scholar Jessica Del Vecchio puts it, “through the weird banality of the dialogue, the audience gets a compelling picture of the life and psychology of this young woman who is struggling to figure out who she wants to be.”

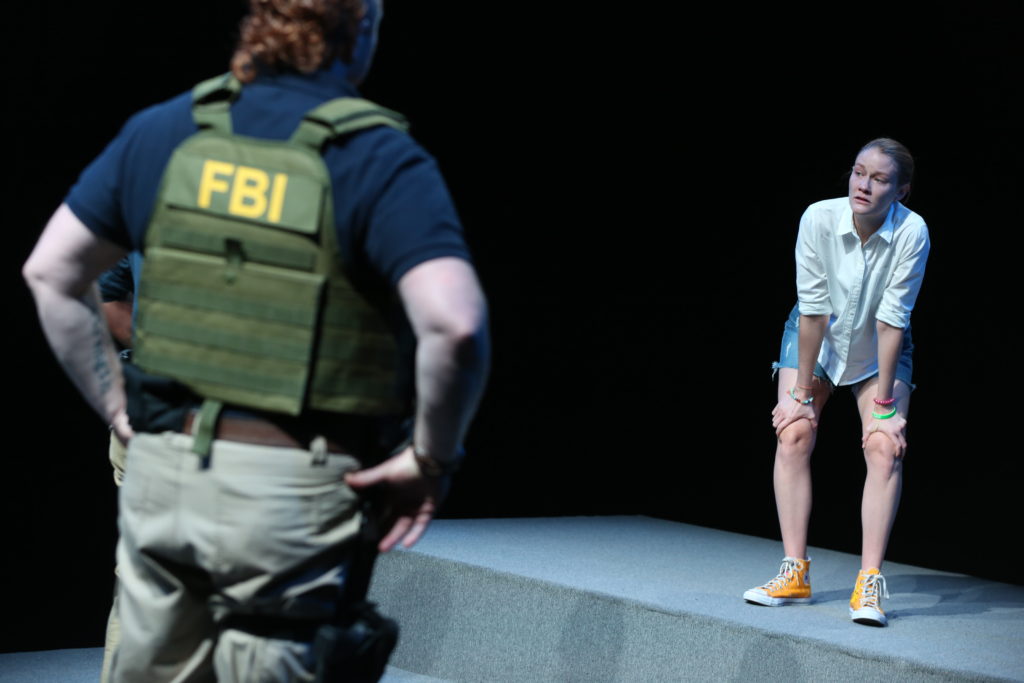

In contrast with the actors’ naturalistic performances, which stay true to every cough, “um,” and redaction on the page, director Tina Satter brings a lean aesthetic to the production: its set consists of a bare gray runway with a small platform and almost no other scenery; performers move in and out of finely-tuned, non-realistic stage pictures that underline the characters’ shifting relationships while abstractly grounding the location of this conversation. Eventually, the play moves into a heightened theatrical landscape, with stark, angled lighting in haze, moments where performances descend into slow-motion, and increasingly-stylized staging of an isolated Reality set against these three agents.

Extended Play’s Daniel Krane spoke with director Tina Satter at the end of the show’s run at the Vineyard Theater about how she and Half Straddle brought this verbatim transcript to life.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

— — —

DANIEL KRANE: You’ve spoken in interviews about cracking this transcript open by breaking it down into three acts, very much like a play. What did that discovery allow you to figure out in this production?

TINA SATTER: We were working on it for several months probably before the idea of the acts cracked into it as a helpful dramaturgical way into it. From the first read I’m like, “This is like a thriller. This is fascinating. The play with language is amazing. The dramatics of this conversation and the fact that this woman’s life is going to be so different in an hour is all there clearly.” But it always felt challenging because of the inherent nature of an interrogation: it repeats itself over and over, like a rhythm. I was always like, “Can we keep all of this?” The goal always being to not cut any of it, which, ultimately, we were able to do. The transcript offered amazing language and offered barks and coughs and overlaps, all this incredible script information, but it didn’t offer stage directions. Obviously, it’s staged on this extremely stark set, but for logic for the actors and for me as a director, it started to become important: just where is she now? We finally figured out, “Oh, that’s when they actually take her.” She goes inside, they put the animals outside and they take her to this room that she says she doesn’t want to go to in her house. The real slipperiness of what those guys are up to doesn’t really start till they take her to the room, because they re-introduce themselves to her at that point. Agent Garrick says, “I’m Agent Garrick” again. “You probably don’t remember who I am. I’m going to take notes.” The logic for us is, that is when the real interrogation starts, and that first third is just all this weird chitchat outside her house. That’s when we were like, “the first act is that.” The second act is this actual interrogation in this little room, and then once she admits. And then the third act was where, once she’s admitted, we were like, “we can really push further on these designs, using tech in it a bit,” going further into what it feels like in her head. Voices feel far away. That’s where we play more with lights. There’s a slowed-down part where the agents talk about her cat. Because we were like, “How surreal would it be for Reality to then hear the agents talking about her cat again?”

She did break a rule, and there is a part of me that’s pretty nerdy and pretty “follow the law.” But I love that space. What are the choices one makes and the sacrifices one makes? That it’s complicated is way more interesting to me.

Tina Satter

DANIEL: That moment blew my mind when I saw the show, because it felt like you set up these really specific rules in the world and all of a sudden the rules were being broken.

TINA: You’re very succinctly getting to what that third act allowed us to do. But it’s still with a rule to break those rules by—because all along, one of our driving factors would be, “What does this feel like in Reality’s head?” That would be a dramaturgical thing we could return to. But we fully allowed ourselves to push there in that third act, breaking some of those earlier rules.

DANIEL: One of the sources of weirdness in the show feels like the character, Unknown Male, that Becca Blackwell plays. They are the one who says, “Is—is this a room? Is that a room?” Could you talk about what role that character plays in the show for you?

TINA: So the transcript notes—I mean, you’ve read it now?

DANIEL: Yes.

TINA: When it lists those participants, it’s like, “Character List,” and seeing a character called Unknown Male was amazing, right? But we also learned that, in real life, eleven men ultimately come to Reality’s house, which we knew from news stories. So then it was like, “Oh! Unknown Male is picking up nine other voices as they pass the two lead agents who are mic’ed.” That was fascinating, because there was that non-sequitur quality to that text on the page attributed to Unknown Male. That was a really breakthrough thought. For a bunch of reasons, we didn’t want to divide this up among nine other actors — mostly cost and just, like, that’s crazy — but then it became this fun thing to play with: “What’s the logic with that character?” They actually represented all these male bodies moving around Reality’s tiny house and outside it. Those men were photographing everything, moving stuff, cataloguing it, so it allowed us to give all these stupid devices to Becca, like a couple phones and weird tools, and then find a way that they were saying stuff in the walkies and to some of the other agents to create this logic for that non sequitur quality of the text. That incredible non sequitur “Is this a room?”: probably, in real life, someone passed on the fly and said that. But once we developed that all that is coming out of one person’s mouth, it becomes this totally surreal, amazing setup.

DANIEL: Helen Shaw has described your work with Half Straddle in the past as “High Feminist Camp.” I don’t know if you’d agree with that description, but this feels a little different than that.

TINA: Yeah.

DANIEL: How do you find that description?

TINA: I mean, Helen’s super, super smart. For years, I’ve had to be a little smarter around what it means when people have called it camp. I still think it’s this gendered read of the work that becomes sort of a limiting code for it, but I don’t actually think she means that that way. It’s a bit of a defensive posture on my side. But I do also think it limits what is at work, just because it happens to have painted nails and femme people on stage in some of those earlier shows. But I think you were asking something more dramaturgical?

DANIEL: I was about to ask something more specific about Reality. Reality seems like a different kind of protagonist— or maybe not— than some of the ones you have had in your work before. She lives in Texas, she owns all these guns, but she also goes to Crossfit and wears cutoff jeans and loves her pets. What drew you to her and how does she fit into the world of the women whose stories that you care about?

TINA: To me, she’s like the women that I’ve been inspired about and writing into my plays the whole time. If you look on her Instagram, she’s this totally girlie girl who also, yeah, owns guns, is totally self-sufficient, speaks Arabic languages, can speak the highest level of security clearance with these dudes in her house because she’s done these really intense, typically male things of being in the military and being an NSA analyst/contractor. To me, she’s not a leap. That’s who I’ve always been trying to write. And I think that answers how it’s seen if you put women in a mini-skirt on stage, they’re just that, as opposed to they are these complicated women who happen to have a femme presentation or a femme edge, which I really think Reality does. Something I’ve said before in interviews is if I had read the article that led me to the transcript about a young man doing what Reality did, I still would’ve been extremely intrigued. But I wouldn’t have been artistically inspired; I just would’ve read it as an interesting article. But I was like, “This female protagonist totally hits at my inner art inspo.” At the time, I was also working on this small piece on Kathy Acker, and I really see this line between Kathy Acker and Reality Winner, too. The thing that was the most challenging to my brain was the male presences that were going to need to be onstage with her and what that meant, because I’ve seen a lot of that. It felt really necessary that, to frame this transcript and to frame Reality that day, there were all these male presences at work on her, and she was lying to and in conversation with them. I was like, “I think it’s really important that we show this masculine code and energy and physicality up there next to the Reality body.”

DANIEL: The way that Reality is able to speak security talk, it feels like, maybe she’s not on Team FBI, but she can at least code switch into the same kind of world that they’re in.

TINA: Totally.

DANIEL: Have you thought about the people in this play as at all like your sports teams in other plays?

TINA: I have. I mean, again, that is exactly why this was interesting to me, because, for theater stuff I’ve made, I like coded groups, whether it’s teen girls or sports plays or four people who happen to be spending an hour in a tap dance class, because of that shared language and shared emotional space that’s super specific. And on that first read, what was interesting to me is that they shared that language. That gave us all this lexicon and jargon and shared stuff that to me is just so interesting theatrically, language-wise and for what it means for a logic of a given moment and world.

DANIEL: Because the design is so spare, everything pops on the costumes and the few props that you actually do have. And the one prop that most jumped out at me was this stuffed animal dog.

TINA: Oh? The dog?

DANIEL: In general, that tension between, “this feels so realistic, this is verbatim,” and “this is not that at all,” was really interesting to me as a spectator. How did you think about the dog specifically in the show?

TINA: For so long I wanted to have a real dog. And the Kitchen [where Is This A Room premiered] is so amazing and hilarious, they were like, “Yeah, no problem.” But then, I was like, this is actually this really controlled show; how would it work? But, literally, there were dogs that people at the Kitchen owned that we were like, “Could that dog be in it?” The animals were ultimately from someone whom I’ve collaborated with before who’s an incredible puppet maker and object maker and designer and artist named Amanda Villalobos. Animals are really important because they’re such a big deal to Reality. We had such a low budget when we first made this at the Kitchen. So, that was sort of the lowest rent version of a dog that could really stand on its own. It’s like that happy accident of making, what the constraint of theater always does—like, this is what’s possible, and then it’s like, “Oh, that is what is so right.” In these other Half Straddle shows, too, there’s often this Mike Kelley sort of world, with stuffed animals or stuffed things filling out a realistic or a semi-realistic set. So that was the dog we had, that was Mickey, which is the name of that foster dog Reality had. But it’s so funny, even when I look at it now — literally I was thinking this watching the run of our show last week at the Vineyard — it does do this real magic tension that I think you just described so perfectly, which always did feel important to me, too, that we are in a room, recreating this day. You know what I mean?

DANIEL: Yeah.

TINA: The first time you make a show is an experiment. We were not doing this and testing, “Did the audience like the dog or not?” We have that dog; that was what had been made and we all loved how it looked. And then, as we performed the show in that first Kitchen run and then ongoing, that meaning of what it means to have a dog that looks sort of stuffed and cheap becomes a really cool tension for us.

DANIEL: Part of what makes this thing theater and live.

TINA: Exactly! Which was always the thing, and then it’s actually evolved how Becca treats it, with a little more shaking that then makes it weirdly real, but it’s still fake. You just get to play with that tool a bit.

DANIEL: I’ve heard you talk about Reality as a young patriot. After having lived with this show for a long time now, do you have a sense of what being a patriot means to you and do you think of yourself as one?

TINA: I still don’t know if I think of myself as one, and that’s something that really struck me about Reality when I read it about her story because I have felt, personally, so disconnected, in a way from 9/11 on — not to go there and get controversial — but it’s like, what does it mean to have a relationship to your state when I was just like, “I hate our country.” Right? I mean, just to be really general and top line and sort of glib and like valley girl fake-intellectual version of myself. It’s gross, it’s embarrassing to live here, even before having Trump in office. Like really complicated feelings, but mostly just being able to feel dismissed from those feelings and do my life, try to pay my student loans, do my work. But this is a person who learned those languages because she truly wanted, in an old-fashioned sense of our military could do, to go to certain parts of the world, be this force for peacekeeping, or help certain populations that needed water, food, protection. And then, when she finds that her country is actually lying outwardly —it’s like, “Duh.” But to feel such a thing of, “I don’t want to live somewhere where they’re not telling the truth,”: it triggered something in me where I was like, “Whoa. It’s so easy for me to feel like there’s no way to really change things.” I mean, I’ve done some activism, but I was struck by a 25-year-old person having what I can read as this patriotic thing—and by that I mean Reality interrogating her own relationship to the United States and its leadership and then taking action on it in a big way. I think what she did is really complicated. She did break a rule, and there is a part of me that’s pretty nerdy and pretty “follow the law.” But I love that space. What are the choices one makes and the sacrifices one makes? That it’s complicated is way more interesting to me. I’ve gotten the gift of being able to share this story now a lot, and it feels really incredible to activate these conversations and be in this discourse that I do care about.

Author

-

Daniel Krane is a Brooklyn-based director, playwright, and arts journalist. He was the Civilians' Editorial and Social Media Intern for the 2019-2020 season. In addition to his work at the Civilians, he served as the Artistic Director at Princeton Summer Theater for two critically-acclaimed seasons, and has worked for the Public Theater's Public Works program and the Brooklyn Arts Exchange. His writing has been featured in American Theatre Magazine, Exeunt NYC, and Extended Play. He received his B.A. from Princeton University in 2018, where he studied Portuguese and Theater. DanielKrane.com

View all posts