Two-Part Names & Other Joys: An Interview with Faith Zamblé

The Civilians' Resident Dramaturg Phoebe Corde sits down (virtually) with Extended Play editor Faith Zamblé to talk dramaturgy, research, and more.

Sign up to get spam-free email updates to ensure you never miss an article and to receive exclusive details about performances and events from The Civilians.

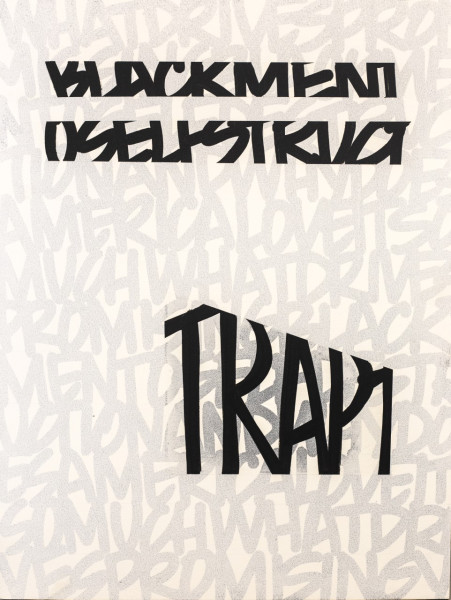

TRAPT poster, courtesy of Stacey Rose

TRAPT poster, courtesy of Stacey RoseThis Monday, December 16, The Civilians is presenting a work-in-progress presentation at Joe’s Pub of TRAPT, a devised investigative theater work by Stacey Rose in collaboration with her son, music producer Zion “No¡z” Rose, and directed by Candis C. Jones.

Originally developed as part of the Civilians’ 2018-19 R&D Group, TRAPT explores the world of trap music, its artists, and its culture, combining live-mixed trap beats with real-world interviews and an original story to get at the roots of the Southern hip hop genre driving much of the music industry in 2019.

Stacey penned a moving piece about what trap music means to her for Extended Play last year, writing, “my relationship with Trap music, / (its simultaneous building up & tearing down of me) / is as complicated as my relationship with this country […] And this is something that, with my son by my side, I will attempt to reckon with.”

In advance of Monday’s performance, I spoke with Stacey, Zion, and Candis about the process behind TRAPT and how that reckoning with trap music is going.

DANIEL KRANE: Why do you feel it’s important to be telling stories about trap music right now?

STACEY ROSE: I’ve been thinking about this a lot here lately. When I started TRAPT, it felt like it was very specifically about trap, and it is, but it’s also about being the narrator of your own story. You find so many times that with different Black music forms, be it blues, be it jazz, the most well-researched, well-put forth stories are not told by Black people. And I think that that is unfortunate because there is a heart and a love that goes into the storytelling about any of our stories, but specifically our music, because our music from the beginning, from the time we were brought here, is what got us through, from gospel to all secular forms. It’s just really inseparable from Black life and Black existence. And this particular form of music, hip hop, yes, and, as of lately, trap and Southern hip hop, has been this lifeline of communication between me and my son that kept us together and kept us engaged even when, at times, we were living apart.

CANDIS C. JONES: Stacey and I talked in a diner years ago about trap and Go-Go music. There was this desire for me to be within and connected to a piece that had the fun and intoxicating sensibility of what happens when you collide a concert and a play. Thinking about how Black people are connected to trap music and also the stories behind survival and resilience that are age-old in our cultural experience within this template of a story was really exciting to me.

ZION “NO¡Z” ROSE: As far as trap music, a lot of people don’t really realize it’s been a part of hip hop as a subgenre for almost twenty years. So it’s great that we get to break it down and that, besides the music side, we get to see what it’s like behind the music and what that person actually is when they not attached to the music. And we get to see what fills them and makes them become who they are when they make a song or a beat or whatever they do.

DANIEL: Zion and Stacey, how has collaborating as mother and son informed your process?

ZION: Really for me, it’s like figuring out a relationship. Doing a show together makes a new bond, because it has to make you figure out how to work with each other without getting too caught up in being, “oh, we’re parents, we’re related,” all that type of good stuff. It gets you more into the state of, “We’re two creative people, two creative souls, and we’re mixing together, and we just so happen to be related to each other.”

STACEY: I have directed Zion before in a short film, but never done something this deeply collaborative with him. I think it’s been, for me, just an extension of the relationship we already have. It has made me grow respect for what he does as an artist ten times over. During this process, I came to understand just how long Zion has been bit with the music bug. Just kind of coming to honor and respect that and encouraging him to bring his ideas or bring his views in. And then, quite honestly, he’s the youth in the project, and he’s keeping me honest. He’s telling me where shit sounds goofy. Or he’s telling me when, “Ma, this doesn’t quite—,” “yeah, but if we did this,” or, “these lyrics don’t quite sound good, but maybe if we did this.” We’re trading off from the base of knowledge that we both come from. He’s coming to me as someone who’s very engaged inside the present-day hip hop music industry, and I’m coming to him as a person who crafts stories and as someone who’s been crafting stories for over a decade. It’s just such an interesting mix. And then you add the interview aspect of it. I often say, when people ask me about it, “I feel like we’re building a play versus writing one.” It’s really been a fantastic challenge. I can’t think of two better people that I want to be engaged in this process with.

DANIEL: Could you talk about what that interview and development process has been like for TRAPT? Where do you think this piece is right now and where do you hope it might go?

STACEY: It’s been a hustle. I’ve done all of the interviewing pretty much on my own, because Zion and I don’t live in the same state. I took a month in August and went down to Atlanta, which is kind of the heart of music these days, but particularly trap music, where a lot of it originated. Memphis is another city. I really just started putting out feelers and talking to who I could talk to and asking who knew who. And, through that, I was able to set up some really solid interviews. One, particularly, with the producer Drumma Boy, who’s been in the field for almost two decades now. This is such a different medium that I feel like there’s a veneer that I have to crack through in order to kind of get the folks I sit down with to understand what I’m trying to do—which is really hard to do when you’re still trying to figure out what the hell you’re trying to do! So, you sit down with these folks and you’re like, “I’m writing a play about trap,” and they’re like, “Oh, what the hell does that look like?” And I’m like, “I don’t know. But I know I want to talk to you about it and I want you to lend your voice. Because you’re a person who’s there. You’re in it. I’m a consumer of the music, and I’m a fan. But what is it like to live it?” And I feel like I’m just scratching the surface in terms of the work I want to do in excavating where the music began, and how the original discoveries were made. I would love to sit down and talk with Three 6 Mafia, particularly Juicy J and DJ Paul, and talk about their production process. The folks that I’ve talked to have all worked pretty closely with the original pioneers, though they’re not the original pioneers themselves. It’s just been really challenging in that, you have to develop this level of trust. But once people figure out that you’re not trying to get anything from them, which—that suspicion is real—you get people opening up and being fascinated with the fact that you are engaging trap music with another art form that is not always looked at really closely alongside it.

DANIEL: It sounds like this is still very much an ongoing process for you guys.

STACEY: Absolutely. I feel like it’s very important to continue the work of really digging in and interviewing folks and still discovering and innovating how this piece is structured. I’m very excited for that and I’m very excited to share where we are at Joe’s Pub. Zion and I just did a workshop at the Playwrights Center, and the actors loved it, for reasons I hadn’t even thought of. There was one actor there from Alabama. He was like, “I just love how fucking specifically Southern this feels.” And while there are plays about hip hop, there are rarely things that discuss things from such a Southern perspective. And that’s just something that comes with the music. You know, I’ve lived equal parts of my life in the South; I grew up in New Jersey. I just have a love for the South. I moved down there when Outkast dropped ATLiens, when André put everybody on notice that The South got somethin’ to say. And I got there just as they were really starting to say it. So I just developed this love for that particular brand of hip hop. It’s just a great voyage that we’re on. And I’m excited to bring an audience in on it.

CANDIS: I’ll add from the bird’s eye view of everything, in hearing Stacey’s post-interview conversations, it feels like she’s injecting the spirit and the tone of her experience speaking to folks into the script. It’s not only leading the structure of her play, but it also feels like there we’re being brought into communities that are deeply steeped in the world of trap and hip hop. There’s a big dramaturgical map to the backdrop of the play thus far.

DANIEL: Stacey, one of the things that you wrote about in your piece was that part of this project is a reckoning with trap music. How is that reckoning going?

STACEY: So I jumped in knowing that trap, and hip hop in general, has had very difficult conversations with women. Very difficult conversations with the presence or lack thereof of LGBTQ folks. And, at this point in time, I still have a deep love for the music. And I felt some of that push-pull back as I was doing interviews, coming in as a woman, and not a young woman, into the process of these interviews. I could feel that contention at times. And that has been something that I have, through continued conversations—I don’t know if reconcile is the right word, but there’s an understanding. There is a great importance for me to meet the artists and the people that I’m talking to where they are, but also command respect for who I am and what I believe in. I think, as I continue to do this work, the same way people can love their racist uncle at Thanksgiving, it’s the same way that I can engage these artists who ideologically I don’t always agree with. But, you know, find a way to make a common ground. And now that I’m just starting to dig into how women fit in this world—one of my fables is around a female artist—I’m very much looking forward to meeting more women and hearing their stories and sharing their stories. Because I do want to hold this music accountable but I also want to show it the love and respect that it deserves as an art form and as an innovative leg of hip hop. So, yeah, still reckoning.

DANIEL: Is there anything else you guys want to share about the piece?

CANDIS: It’s amazing to work with Zion as a producer and witness the fresh perspective he’s offering into the genre of devising. I’ve never worked with a music producer live, within a piece. And for me, the most important thing is creating this improvisational nature within creating the piece, and leaving some of that in performance. While there are things that we will have cemented, especially for the presentation, I think in the long run, for the production of this piece, there should always be space for a really live, unpredictable element. So night to night things can change. And that is, if Zi decides that he wants to explore something sonically, there’s always space for that. That’s where my mind is in creating a live piece of theater that melds various styles and genres.

ZION: Shout out to my mom and to Candis. You guys, for the theater side, y’all are the cornerstone that makes people really like hip hop and like trap. Because y’all make people understand what it’s like. And what I mean by that, it’s sort of like, people didn’t really understand N.W.A. until the movie [Straight Outta Compton] came out. And the reason why they understood it was because they were seeing their lives without the music. So it was like, they seeing how Eazy-E was without his persona. How Dre was without his persona. How Ice Cube was without his persona. How they are actually like a human. And see that world and think, “Damn, he’s just like me in some ways.” I appreciate that.

STACEY: Even with the Wu-Tang show, having the artists be a part of creating the narrative, so that their story is told in a way that reflects their actual experience I think is, when you boil the meat off the bone, what it comes down to. And why it’s so important for me to continue engaging with artists across the, now, generations of trap music. What you’re going to start to see is just different faces of what it means to be Black Americans from particular areas. Which I think is very, very exciting and makes me feel a little like an archeologist.

DANIEL: I’m willing to bet a lot of the people who come to see this in New York have probably never seen a show in Joe’s Pub that’s telling the story of this specifically Atlantan, Black music.

STACEY: I’m willing to roll the dice to say they haven’t. I feel like it’s going to be a very special experience and one that I’m excited to jump into.