In 2008, Linda LaScola and Daniel Dennett began work on a new study: a look into the lives of practicing clergy members who have stopped believing in God. The Unbelieving, produced by The Civilians and opening on October 27th at 59E59, is a play composed of the real words and stories shared for this project by Catholics, Episcopalians, Evangelicals, Fundamentalists, Jews, Mormons, and Muslims who must decide whether to continue living in secret or risk everything by telling the truth.

Ahead of the show’s opening, The Civilians’ Resident Dramaturg, Phoebe Corde, sat down with Linda LaScola, who is represented in the play as a character, and Marin Gazzaniga, the playwright tasked with creating theater from those interviews, to hear more about how the project came to be, the writing process, and their perspective on creating theater about religion.

PHOEBE CORDE: How did you two connect for this project? How and when did the idea of writing this piece come to be?

MARIN GAZZANIGA: I believe it was Dan’s wife Susan who first suggested that it should be a play. When Dan and Linda were working on the book and reading the transcripts, it felt like scenes to Dan that he wanted to see come to life.

Linda and I connected via Dan. He and my father are colleagues and friends and I think they had a dinner where Dan told him about the study and that, reading the transcripts, he thought it should be a play. My father told him I write plays. My first play was based on interviews when I worked at Victim Services, and was about domestic violence. And I started in journalism so I am committed to accurately depicting a story. I had also recently written a play about science and faith. I sent Dan those plays and he sent me Caught in the Pulpit (the book about the study) and I was fascinated. I told them I felt that the power would come from using the clergy’s words, and he and Linda agreed. We went from there. I went through an IRB training (Internal Review Board) via Tufts University on the proper treatment of human subjects in order to be able to read and work with the transcripts. Linda reached out to the study participants and 19 agreed to let me read their transcripts for consideration for the play.

LINDA LASCOLA: As Marin said, it was really all through Dan Dennett, whom I had done the study with. I know that Dan said, from the very beginning when he started reading the transcripts, that it seemed like drama to him. And I really just laughed it off. I mean, I thought it was interesting what he said, but — this study was more dramatic perhaps than some of the other ones I’ve done, but I just thought of it as a study. You know, I didn’t think of it as drama and I wasn’t really that familiar with drama at that time. So, when he said it was drama, it’s not that I didn’t take it seriously, it’s that I didn’t think it would work into anything as it has.

PC: What about this story says “theater” to you now, then, rather than another creative medium? What made you think of it as drama?

LINDA: Now that it’s become a play, I can see that it’s theater, and I get choked up every time I hear it, even though I’ve heard it a million times and it keeps changing. So I know that it’s theater, but I didn’t really think of it that way at the time.

MARIN: Theater to me is human drama. I drop into a piece when I see human emotion. I respond to that more than spectacle. And this is a story of people grappling, in real time, with the meaning of existence. With existential crisis. What’s more dramatic than that? This being a theater piece allows us to have that intimate experience. To eavesdrop in the room where these conversations are taking place. In some ways, it’s like what a religious service offers: a place to have your own personal thoughts and reactions, but in a communal setting that makes it both personal and public at the same time.

PC: Yeah, I’ve heard theater compared to a religious experience in the past — a group of people coming together to hear a text or a story, trying to find truths and meanings in it and leaving the experience thinking. And, we even have — one of the people in the show refers to being up there [in the pulpit] as “roleplaying.” It’s a performance as we sit in our pews in the theater.

MARIN: It’s not even just the performance; it’s the audience experience, which is: you come to the theater and you’re sort of alone with your thoughts and you get to sort of process the information that’s happening and have your own thoughts and feelings about it, which I think happens in a religious service when the preacher is up there preaching. I also think that, for a lot of artists, theater or art or creativity is their religion. It’s where you connect to some sense of something greater than yourself. So theater feels like the right venue for it, or the right medium in that sense.

LINDA: And as an adult, I’ve heard Catholic and Episcopalian services referred to as theater. And they definitely are. I mean, it’s no accident that the priest is wearing the robes and they have music and chanting and ceremony and incense and bells. That’s what I really love about the church. I still go to Easter and Christmas. I drag my husband, who’s not interested at all and wonders why I am. But I love the theater of it.

PC: Marin, how do you approach writing a piece like this, that’s made up of the real words and people’s experiences from this study?

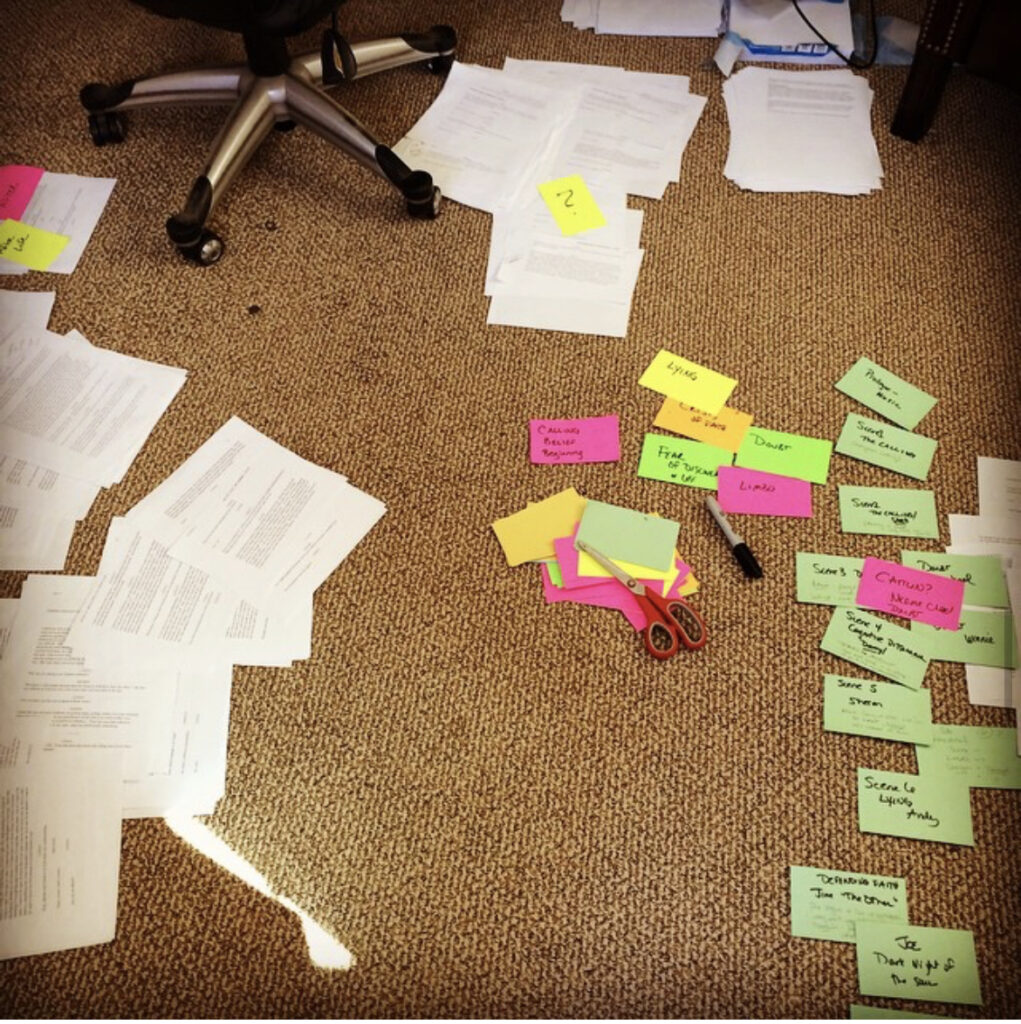

MARIN: I started by reading the interviews. I never listened to the recordings. In fact, I wasn’t allowed to because of the restrictions of the study. And I agreed with Dan and Susan, the drama jumped off the page to me. As did their voices. The “scenes” were pretty clear to me from the beginning. I would just sort of highlight what jumped off the page as scenes. I would pull excerpts and have actor friends read and discuss them. Many of those first scenes are in the play.

The challenges became figuring out how to whittle down the thousands of pages of material. Each interview could have each been its own play. But I did see certain common experiences and themes in their struggle. I wrote themes on postcards — doubts, faith, loss — that emerged in everybody’s story and, over time, reading it all, I saw a similar arc that they were all going through. Yes, their details were individual, but there was something similar about the journey of going from believer to nonbeliever, and so I started to sort of divide them up by those categories. I ended up using Adam as the central character since he had the biggest arc during the course of the study, and he actually came out publicly as an atheist during the course of writing the play. And the other characters tell parts of the story. So together, the individuals tell the story of what it takes to go from believer to atheist.

LINDA: I was very impressed by Marin’s ability to pick out just the right things from the interviews. I had been there during the interviews and, in some cases, I had actually encouraged the people to say what they eventually said — I mean, I didn’t know what they were going to say, but I could see they wanted to say something and I pulled it out of them — but I didn’t see it the way Marin saw it at the time. I just saw it as doing my interviewer’s job, allowing them to express themselves.

PC: And, specifically for you, Linda: how does it feel seeing yourself brought to the stage in this way? And getting to work on this as a creative pursuit rather than as a research pursuit?

LINDA: It was extremely weird. Very, very weird. Not only seeing it come to life, but how seeing other actresses depicted me. And to see my friends and colleagues reactions. I’ve had colleagues react to the play all along — these are qualitative researchers who happen to live in New York City and some of them have come to either all or some of the readings. They’ve seen the play evolve and they’ve seen the character evolve and they also know me as a person and they know what qualitative research is, so it’s been interesting getting their perspective along the way.

And the most fascinating thing is to see how my colleagues react to my words, which Marin uses in the play, in different actress’s mouths. In most cases, they say, “Isn’t this interesting. This is good.” And other times, they say, “Linda, my god, how could you have possibly said that?” It was just in the delivery of the actress, not in my own delivery, and it was not problematic during the interviews at all. Some of the participants in the study were so eager to talk to somebody who wanted to listen, that they didn’t care so much about me not always being sensitive. They didn’t think, “Is she sensitive?” They thought, “My god, she’s talking to me! She’s asking important questions! And I’m having a chance to unload all of this stuff I’ve been carrying around.” So I think, in that sense, they were easy to respond to. And in another sense they were difficult, because of what they were going through.

PC: What do you hope audiences walk away from this show with? Does that change if they’re a believer or a nonbeliever?

MARIN: I hope audiences walk away with a new understanding of the “other” – whether that’s believer or non-believer. And that it makes people reflect on what they believe, and why. Are we making conscious choices?

When we were at the Santa Fe Institute doing a presentation of early excerpts of this, Dan said something that really struck me: “Nobody changes their mind in public.” Working on this play has opened my eyes to how profoundly difficult it is to change your world view. And yet 50 percent of us in the country right now want the other 50 percent to do just that. It’s not an easy thing. The clergy in this play are phenomenal human beings who grappled with life’s big questions, and shared those struggles with us because they believed it was important to speak their truth. And some of them have been willing to take the risk to change their mind in public.

LINDA: I want audiences to feel as if they have learned more about these people. A lot of people, when I was conducting this study, said, “What? Nonbelieving clergy? You’ve gotta be kidding me. What kind of people are these? Who among the clergy doesn’t believe?” And so, I want the audience to see them as regular people and see the pain they’re going through. Does it change? I really can’t answer that yet. I’ll know that when I see the play. It’s more that I’m looking at it from a researchers point of view. I’m open and I want to see how people react to it rather than saying what I expect.

MARIN: I feel like I’ve gone on the journey that Linda went on, and the audience goes on it, too, which is: to come into this with a little bit of skepticism. I think Dennis says at some point in the play, people think, “How could you think this way? Either, if you’re a believer, it’s, “You didn’t really believe hard enough. You didn’t work to overcome your doubt,” and people who are already nonbelievers think, “Oh, how could you be so dumb to believe that thing?” So I think that if those two people come into it with those points of view, hopefully they’ll have a better understanding.

I was struck, too, by — some of the designers on this show talked about why they wanted to do this, work on it, and Sean [Donovan], who’s our movement choreographer, said he was struck by the fact that [the clergy are] grappling with these huge questions about the meaning of existence that most of us don’t really think about in our everyday lives. And how moving that is. You know, that by questioning this, they really had to face some really big questions about: Why are we here? What is the meaning of life? Listening to these people talk about this stuff, it makes you look at your own beliefs and think more deeply about them. Like, “What do I believe, and why do I believe it? And what is my relationship to religion?” because I think, whether you’re a believer or a nonbeliever, we all have a relationship to religion in this country. You either had it a bit as a kid or you’re deeply involved in it or you’ve rejected it, but it’s something that touches all of us, and the degree to which we think about it and our relationship to it is not something we always think about. So I think that would be another thing that I would think or hope people come away from the play with.

The Unbelieving is running through November 19, 2022. To purchase tickets to and learn more about The Unbelieving, visit 59E59’s website or click here.

To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit our website TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

Phoebe Corde (she/her) is a dramaturg, writer, and illustrator from Westport, Connecticut, specializing in stories of the strange, magical, and otherworldly. She is currently Resident Dramaturg at The Civilians, where she is director of their artistic development group, the R&D Group, and is a member of the creative board of directors at Off-Brand Opera. Her dramaturgical work has been seen on Broadway and Off-Broadway stages, including The Public Theater, Vineyard Theatre, A.R.T., Paper Mill Playhouse, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Ensemble Studio Theatre, and 59E59.

View all posts