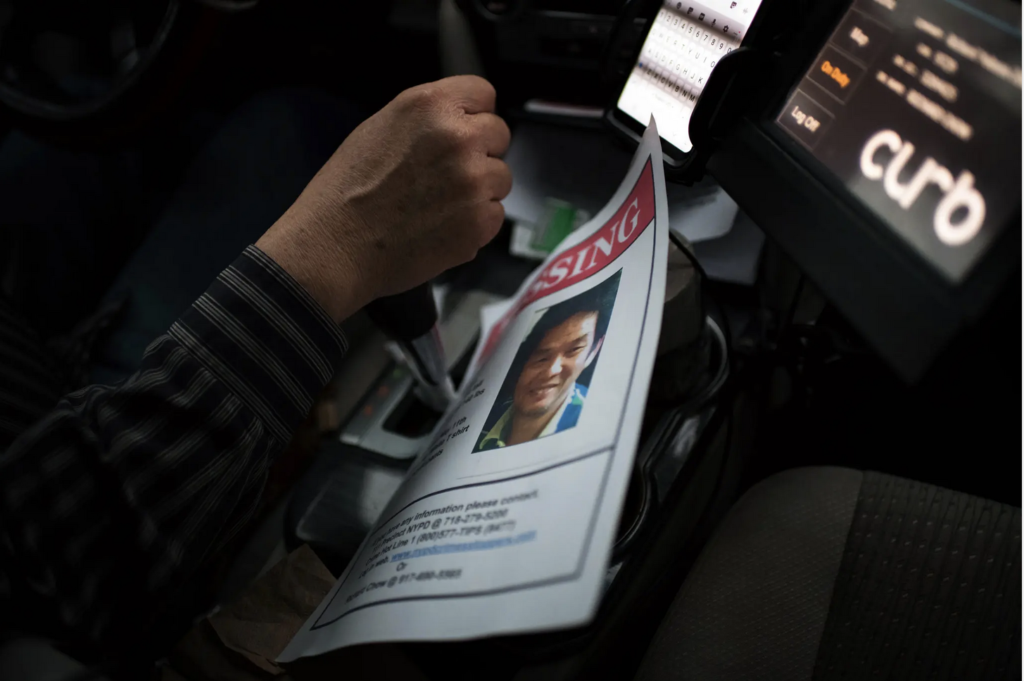

The New York Yellow Cab is iconic. You see one, it brings up a tangle of associations, all the history and myth of a legendary city. The cab is the backbone of a city that never sleeps, where you just have to get somewhere no matter how tired you are or whether you picked the right shoes that day. The service is necessary, and the job was often the best way for someone to build a middle class life—especially someone coming from another country and starting anew. A disproportionate number of New York City cab drivers are immigrants, particularly from South Asian, East Asian, and African countries.

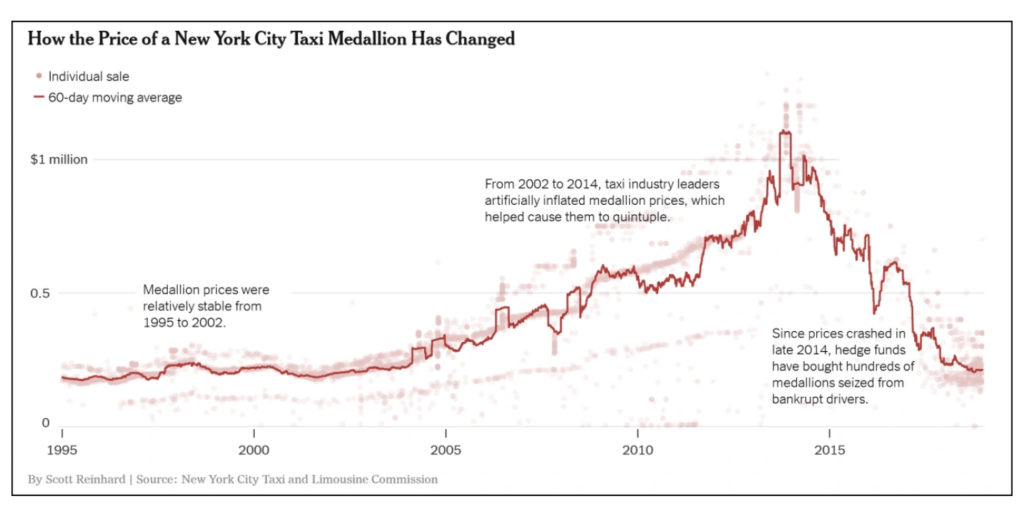

The pathway to the middle class for a New York City cab driver runs through something called a Medallion. A Medallion gives a driver the exclusive right to drive a cab in New York City. Since the supply of Medallions was fixed and expanded only very deliberately by the city (always with the intention of keeping the number of drivers slightly less than the demand), the Medallion maintained a high value. Unfortunately, it also meant it was a lucrative betting market, inflating the value of Medallions to absurd levels. That meant a driver who wanted a Medallion would sign up for hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, which would be paid off over time in monthly installments. When times were good, there were few drawbacks. If a driver failed to make their payments, the medallion could go to someone else. The consequences were light, the risk was low. The times aren’t good, though.

Rideshare apps toppled the house of cards. They offered a convenience to the passenger, like hailing a driver with your phone instead of the familiar dance along the street. This meant it was harder (but still not impossible) for passengers to be refused rides for petty reasons. For drivers, it offered one of the easiest entry-points for people to become drivers. Many of the changes were welcome—but I don’t think most people are aware of the cost. Companies like Uber and Lyft were able to circumvent whatever legal protections kept cab drivers the exclusive service in New York City. Without regulation, control over the supply of drivers was largely taken away from the city—this was the main mechanism that secured the medallions’ value. So not only did ridership for yellow cabs decrease, hitting drivers’ take-home pay directly, the value of the Medallion to which they were making payments dropped severely. Lenders cracked down, payments went up, the foundation of these drivers’ and their families’ lives crumbled.

Eight drivers committed suicide, struggling to make their payments in this landscape. One story that grabbed hold of me was that of Richard and Kenny Chow. Two brothers who stayed together since they were children in Myanmar. Kenny, the younger brother, committed suicide after his payments became impossible to make, and his daughter had to leave school to help care for the family. No statement was left, except that he parked his cab for the last time in view of the Governor’s mansion.

His death precipitated revived and emboldened organizing among cab and rideshare drivers with the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. One of the common chants was “No More Suicides.” The protests turned into a hunger strike, which lasted two weeks. Finally, they won a huge concession: payments were capped at far below the current rate, the city agreed to guarantee a portion of the debt, and there was finally a viable path out from otherwise crippling debt. Despite many not having eaten in two weeks, when they found out, they got up and danced.

It’s an incredible story, a ray of hope in what can feel like a bleak world. It showed that, once again, direct action gets the goods. I was inspired. But how would this become a play? The potential paths were overwhelming. When I first pitched this project, I called it a new Waiting for Lefty. It was more of a short-hand than anything else, and my vision for the project has shifted and evolved as I’ve spent more time with it.

The biggest challenge of this process has been freeing myself from reality. This might sound strange when describing a piece of investigative theatre. But I was not interested in creating a facsimile, as heroic as the events were. It’s been immortalized, it’s been preserved. You can read and hear their words, you can watch them speak, you can see the strikers break into dance when they finally won. I’m not sure what a faithful theatrical interpretation would add to this conversation. It would also shift focus to how accurate or inaccurate the details are, rather than what I found more interesting, which was what could be. In any case, it was not what I was interested in as a writer—and rarely does something good come out of forcing a project like that. I’m sure another writer would knock that play out of the park, though.

As a writer I love mythologizing and fabricating. It’s rare that I feel compelled to craft a “based on a true story” narrative that is not refracted in some way. To me, this moment was a tear in fabric. You could see that anything was possible. And that’s how I approached this play. Rather than dig up the same story, going over the same details again, I wanted to make something that stood on its own. I also wanted the freedom to expand the scope of the story to the larger context. How did this fragile structure get built and why? How does this connect to other labor struggles in the US and the rest of the world? What global events led to people even coming to America and being in this position? What goes into the moment when the water boils over, when the quantitative change leads to qualitative change? And honestly, what goes on in the head of an executive at a company that invests in Medallions?

The people who have created and exacerbated this problem continue to thrive in the top positions of power. The aspects inherent in the system which caused this issue (and has and will cause the issue to occur again and again), continues to be defended, rationalized, or even just mystified.

The play took on an even greater relevance with the success of the Amazon Labor Union and Starbucks union drives. A union is the only way workers have any control over their lives and livelihoods in a capitalist system, and since the adoption of neoliberal social and economic policies, unions have been repressed with all kinds of legislation and intimidation. I’ve talked with organizers who were dismayed by the climate for organizing. There were so many tools companies had at their exposure, so much money, and in the case of Amazon, their employment structure was based on high turn-over, which made establishing connections difficult.

There are similar struggles with the job of the cab driver. You spend your days mostly alone and in competition with your coworkers. There is a social fabric, and drivers do have places to meet, but the atomization of workers in this type of work is an obstacle. And yet the New York Taxi Workers Alliance has been able to create a space where taxi drivers, rideshare drivers, limousine and livery drivers—all the varieties of drivers in the city, some of whom might perceive themselves as having opposed interests—can work together to take charge of and better their lives.

What I hope to do with this play is illuminate connections that might be missed, contextualize the struggle, and inspire others to challenge what they believe is possible. We are in a time when this kind of action is the only thing that will get us through. There should be a space in theatre to wrestle with that and imagine new possibilities.

Aeneas Sagar Hemphill (he/him) is an Indian-American playwright and screenwriter based in NYC and DC. Weaving through genres, his work builds new worlds to illuminate our own, using passion, pathos, and humor to investigate the ghosts that haunt our lives and communities. His plays include: Karma Sutra Chai Tea Latte (Gingold Speakers’ Corner), Black Hollow (Argo Collective, Dreamscape Theatre), The Troll King (Pipeline), Childhood Songs (Monson Arts), The Republic of Janet & Arthur (Amios), The Red Balloon (Noor Theatre), A Stitch Here or There (DarkHorse Dramatists, Slingshot Theatre), A Horse and a Housecat (Slingshot Theatre). MFA Playwriting, Columbia University.

Extended Play is a project of The Civilians. To learn more about The Civilians and to access exclusive discounts to shows, visit us and join our email list at TheCivilians.org.

Author

-

Aeneas Sagar Hemphill (he/him) is an Indian-American playwright and screenwriter based in NYC and DC. Weaving through genres, his work builds new worlds to illuminate our own, using passion, pathos, and humor to investigate the ghosts that haunt our lives and communities. His plays include: Karma Sutra Chai Tea Latte (Gingold Speakers' Corner), Black Hollow (Argo Collective, Dreamscape Theatre), The Troll King (Pipeline), Childhood Songs (Monson Arts), The Republic of Janet & Arthur (Amios), The Red Balloon (Noor Theatre), A Stitch Here or There (DarkHorse Dramatists, Slingshot Theatre), A Horse and a Housecat (Slingshot Theatre). MFA Playwriting, Columbia University.