Steve Cosson and Cynthia Hopkins discuss their different theatrical journeys through the Arctic to address the global climate change crisis.

In 2010, theater artist Cynthia Hopkins joined an arctic expedition as a project of Cape Farewell, a UK-based international not-for-profit program that brings together artists and scientists to stimulate cultural dialogue around climate change. From her experiences sailing through frigid seas around the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, Hopkins created “This Clement World,” a musical performance piece that layers tropes of investigative theater with invented time travelers, ghosts, and choral folk opera. “This Clement World” premiered at St. Ann’s Warehouse in 2013.

Having also explored the global climate crisis in his show “The Great Immensity,” the Civilians Artistic Director Steve Cosson sat down with Hopkins to discuss how investigation and imagination can illuminate our relationships to the natural world.

STEVE COSSON: “The Great Immensity” is actually the first fictional play that I’ve written, which has been rather terrifying. A lot of it did come from research, but in making the show, we kind of went out on a limb. And I didn’t necessarily know what kind of show it was going to be, whether it was going to be verbatim or whatever. I had no clue and felt like I had to go out and into the world in a dramatic way to get inspiration and digest it all for a while. And then I realized it needed to be a play. A narrative play.

I saw “This Clement World” as I was in the throes of working on “The Great Immensity,” and I was really struck by it. There were a lot of uncanny parallels. But before I just start talking about those, I want to hear about your process. Were you thinking about making something about the environment or about climate change before the opportunity with Cape Farewell presented itself?

CYNTHIA HOPKINS: Yeah, I mean, I’m pretty sure I got invited because I had decided already to make something about climate change. That happened because I got invited to a conference organized by Tipping Point, which is another British organization. Basically it has the same mission as Cape Farewell, which is to foster dialogue about the climate crisis through the arts by bringing artists and climate scientists together. So Cape Farewell does it by organizing these expeditions and these treks into the wilderness — usually the Arctic — and Tipping Point does it by holding conferences. I got invited out of the blue, and I was in the middle of working on a totally different show. I was already curious about the issue at that point, and that’s why I decided to attend the conference. But until that point, it had never occurred to me to address it in my work.

“Artists can communicate in ways that are potentially more powerful, potentially more inspiring, and accessible, and entertaining than journalists or scientists can.”

The opening speech of the conference was by a climate scientist named Wallace Broecker. And at the time I believe he was 79-years-old — late 70s, early 80s. After this opening speech, we were put into groups and given this assignment to create a succinct message about the issue, and we had a very strict word limit. And that was a great assignment, because restrictions are a form of freedom and a form of inspiration. I write lyrics a lot, but I really loved the exercise of being forced to employ extreme economy expression. And so I wrote a song from the point of view of Wallace Broecker. His speech was inspiring, because he is a compelling character. He is quite an old man. He’s been studying climate science his whole life; he coined the term “global warming” in the 1970s. He discovered the oceanic conveyer belt, which pulls gulf stream waters up north and has a big influence on the climate of the planet. So he’s this very knowledgeable, renowned scientist, and I expected him to give a speech about exoteric theories. And instead — first of all — he was dressed in a plaid shirt and jeans, and he was a really charming guy. He just spoke from his heart.

The first thing he did is sigh deeply. And then he said, “You know, I wish I could live another fifty years or so, because we’re at a turning point of human civilization. What we do now, and the choices we make now, are going to drastically influence which direction the planet, the environment of the planet — and by extension human civilization — go. And it could go any number of ways, depending on what we do and what government policies forces us to do.” And he said, “I’m really curious.” It was this beautifully personal point of view. It called to mind instantly mortality as individuals — because he’s an old guy — and also our great, larger forms of mortality. So that speech made me want to make something about the issue.

The next day there was another speech by a guy named Jeffrey Sachs, who writes about sustainability. He talked about communication around the issue of climate change and how, because of the vested interests of large corporations whose whole business is fossil fuels, there’s been a great deal of miscommunication. It’s not in their economic interest for people to be veering away from the use of fossil fuels. And there was an artist in the audience who said, “What can an artist do about this issue, or how can an artist contribute to this issue in some way?” And he said, “Artists can communicate in ways that are potentially more powerful, potentially more inspiring, and accessible, and entertaining than journalists or scientists can. And part of the reason for that is that they can communicate on a more personal level.” And we can also use inventive fictional forms.

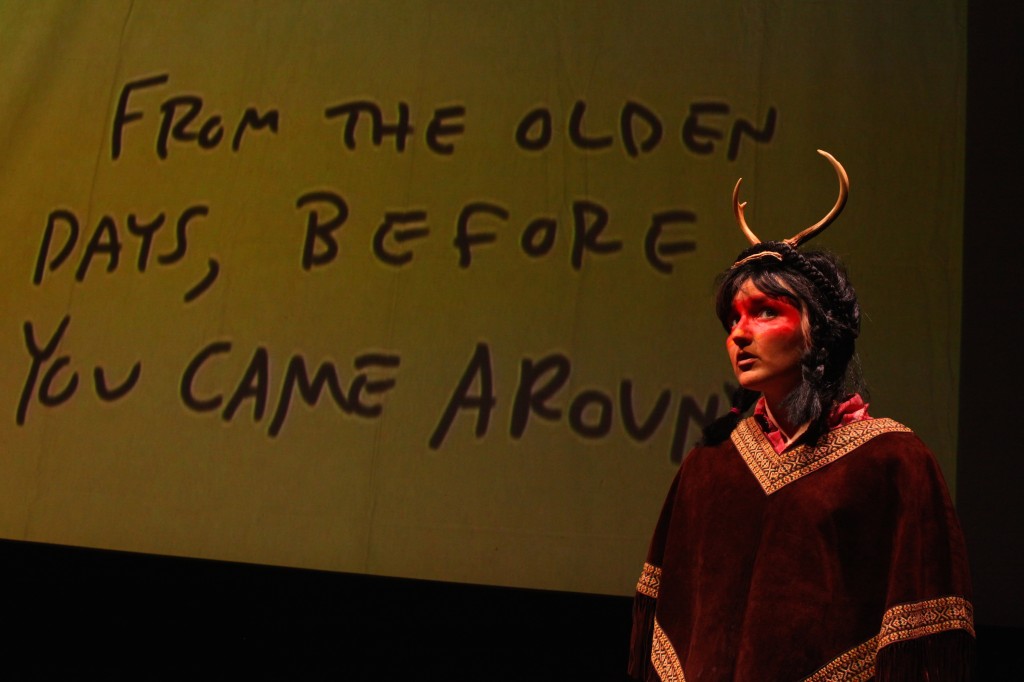

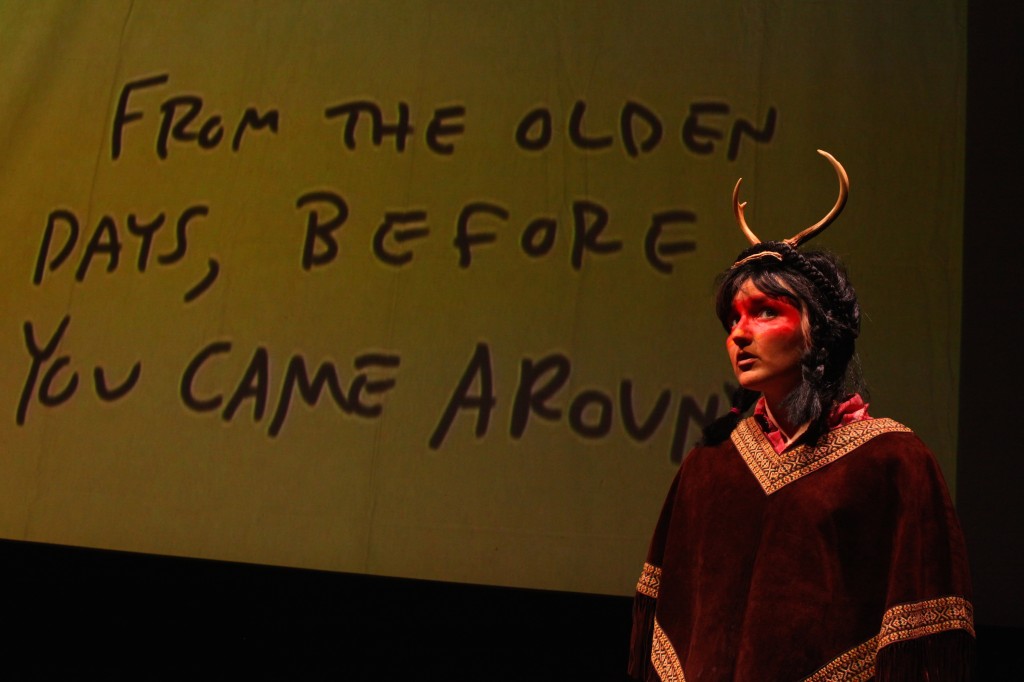

Cynthia Hopkins in “This Clement World.” Photo credit: Paula Court

In my piece, there are fictional characters from the past, from the future, from outer space. From my perspective, part of the challenge of talking about this particular issue is that it really requires an athletic use of the imagination, because it involves gasses we can’t see. So we have to imagine them. It also involves time spans and space spans that are way beyond our individual life time. Jeffrey Sachs likened artistic communication to the work of a translator — basically taking ideas from one realm, like the scientific realm, and translating them into the language of that particular artist and that particular form, whether it be music or colors or whatever. It’s about translating that information in a way that you can understand it. Or feel it. Or grasp it. Or imagine it.

So, after that weekend, I wanted to make something. One of the other people there was a dramaturg named Ruth Little, who worked for the Royal Court Theater at the time. And she had seen my work, and I said to her, “I want to make something about this issue.” And two months later, she sent me an email: “I have left the Royal Court Theater, and I work for Cape Farewell now. We’re planning an arctic expedition. Do you wanna go?”

STEVE: Do you want to get on a little boat in the arctic?

CYNTHIA: And I said, “Do I have to pay for it? Because I don’t have any money.” And she said, “No, Cape Farewell will pay for everything.” And I said, “Then I absolutely want to go!”

There’s a museum in Longyearbyen — which is where we sailed out of — about life in the arctic, and it talks about the survival techniques of different species that live there. The reindeer, it said, they lead tranquil lives. That’s their survival technique; they just keep it very simple and don’t do very much. It’s incredible that life is there, so it can inspire hope, as well, that life is resilient, and that it’s adaptable. And hopefully — even with all of the incredible damage that we, as a species, have done and are doing to the environment — we maybe work it out somehow.

STEVE: Looking back on it all now, did you have any ideas of what your piece might be, or did your relationship to the subject change directly as a result of the Cape Farewell journey?

CYNTHIA: I wish I had the power to allow everybody in the world to go on that trip, because it’s so breathtakingly beautiful. And it’s also a transformative experience. It does make you feel your own mortality, but it also is a really palpable experience of how miraculous life is, that life exists at all. Somehow this convergence of the right ingredients came together on this planet in a way nobody really understands. We were hiking in the frozen tundra one day in the middle of nowhere, and we came upon this little arctic fox. And he’s beautiful, and he seems like a pretty happy guy, and he’s surviving this climate that seems totally inhospitable to life. You hike for miles and miles and miles across the frozen tundra with freezing wind blowing in your face. You can barely see because it’s so cold. And you come over a ridge, and there’s a reindeer family — big, fat reindeer, with these gigantic antlers, and they’re munching on what looks like scraps of moss in the ground. How could you survive here? And yet these creatures are totally doing it. They’re doing it really well.

-

-

Snapshot from Cynthia Hopkins’ trip around the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, on which she began developing “This Clement World.”

-

-

Cynthia Hopkins and Captain Ted aboard the Noorderlicht.

-

-

“You’d hike for miles and miles and miles across the frozen tundra with freezing wind blowing in your face. You can barely see because it’s so cold. And you come over a ridge, and there’s a reindeer family. Big fat reindeer with these gigantic antlers, and they’re munching on what looks like scraps of moss in the ground. How could you survive here? And yet these creatures are totally doing it. They’re doing it really well.”

-

-

Cynthia Hopkins in “This Clement World.” Photo credit: Pavel Antonov.

-

-

Snapshot from The Civilians’ trip to The Churchill Northern Studies Centre in Manitoba, part of the development process for “The Great Immensity”

-

-

Erin Wilhelmi and Dan Domingues in The Civilians’ “The Great Immensity” at The Public Theater, 2014. Photo Credit: Richard Termine

-

-

Snapshot from The Civilians’ trip to The Churchill Northern Studies Centre in Manitoba, part of the development process for “The Great Immensity”

-

-

Rebecca Hart and Dan Domingues in The Civilians’ “The Great Immensity” at The Public Theater, 2014. Photo Credit: Richard Termine

-

-

Snapshot from The Civilians’ trip to The Churchill Northern Studies Centre in Manitoba, part of the development process for “The Great Immensity”

-

-

Damian Baldet and Rebecca Hart in The Civilians’ “The Great Immensity” at The Public Theater, 2014. Photo Credit: Richard Termine

When I went there, I didn’t know what I was going to make. I remember making a list of possible ideas, and it was a long list. And it was everything from a piece in total darkness, where it was just a sonic piece, and you were only getting information and music so that you had to really make a picture in your mind. Another idea was to have an installation that would demonstrate different sorts of energy. The fictional characters actually came out of that idea, because I thought, “Well, if it’s a museum, there should be tour guides.” It would basically be an exhibit about energy and life on this planet, the clemency of the planet, and how the clemency of the planet is fragile. And so that’s where the figure from the past, the figure from outer space, and the figure from the future came from. We need to expand our imagination to encompass a time before humans were even here. The planet itself has been inhospitable to human life for the vast, vast, vast majority of its existence. Humans are these tiny, tiny, tiny, little blips in the timespan of the planet.

I had a video camera, and I started to get interested in the other people on the boat. I thought, “Okay, I wanna start interviewing them.” But when I got home from the trip, I thought, “Okay, I’ll make a series of pieces, and one will be this documentary about the trip.” Because I had all this beautiful footage, I thought that would be one piece, and then this installation of the tour guides would be another piece, and then this piece in the darkness — where people had to imagine things — would be another piece. And so I just started making little parts of each of those, thinking they’d be separate. And then I had to give a showing somewhere of some material. I had edited some little documentary sequences, and I had created these fictional characters. So by the time I get to this university gig, I have little bits of video documentary, and I have these character monologues and songs, and I even said to the audience, “These are not the same piece. These are from different pieces. They’re totally separate, but I’m just putting them together, because I have to change my costume between the tour guides. And I have these documentary things I can play while I’m changing my costume.”

In the feedback session, there was a professor who taught music composition, and he said, “Oh it was like point and counterpoint in music.” So you would listen to the point — which is the documentary, because it has a little bit of a monotonous quality, which documentaries kind of do — and then the tour guides happen, and they’re like a break from that. And when you come back to the point, you hear it differently, because of whatever perspectives that counterpoint has introduced. And so that experience made me think. That experience basically shaped the remainder of the making of the piece.

“We need to expand our imaginations to encompass before humans were even here.”

STEVE: It’s fascinating to hear, because I think — as with any creative process — so much of it turns out to be chance or the right person being there at the right time. Those people happened to be in the audience when you did your showing, and — by offering their perspective — they made you think about it in a different way, which then set you onto a different path.

CYNTHIA: Yeah, in that way, it’s really like science. It’s trial and error, you know. You read about Galileo and people like him — most of discoveries are frequently mistakes. They think they’re setting out to find out one thing, and they end up discovering something like gravity or, you know, some other thing.

STEVE: It’s funny that you were just talking about that — the aspect of time in your piece, that we are a little blip in this larger history of the Earth — because, without getting too much into “The Great Immensity,” that was sort of my starting point. That’s how I ended up in climate change.

Melanie Joseph wanted me to write a show about time. And I got most interested in what I was viewing as the disjuncture between our cultural ability to understand time — living in human time, where a lot of stuff happens in really short increments of time relative to geologic time or natural time or the time of the planet — and how we’re in this weird moment. Now our technological abilities have made it possible for us to make these huge changes on the geologic and natural time scales, like changing planet systems. And so then culturally, we don’t have the imaginations to fully appreciate and live with the reality of what we are actually able to do, which is a funny disjuncture. That is a big part of where the artists — or the communicators — enter into this picture. Because it’s not abstract stuff that we can’t comprehend, its stuff that’s actually happening. It’s real stuff. It’s real stuff that we are able to do, but can we actually imagine what we’re doing?

CYNTHIA: I think it’s very hard to imagine what we’re doing. We have, at this point in human history, a really weird — or at least unique, unusually detached — relationship to the natural world. I think we live in a very alienated moment. I think there’s a general sense, at least a general sense that I feel, of alienation from any other part of the earth. And I think that’s really sad, and I think that’s really dangerous. Just to give a shout-out for theater — I mean, for me, one of the things I love about the theatrical form, especially in this day and age, is that it’s increasingly important. It’s this space of reflection, in terms of time. Especially with increasing digitization and people always scrolling their iPhones — you see people sitting across a table at dinner from each other at a restaurant, and they’re both looking down at their iPhones. And so, for me, I really cherish the space of theater. It’s a space of reflection, where time slows down a little bit. I really love the fact that it’s a collective experience, because I think digitization also increasingly separates us from one another, even though it’s this device for increasing connection and global connection. I feel like it also has this very alienating effect, a kind of isolating effect. And I think that people sitting in a room together is really important. I think it’s really ancient. And so it’s curious to me that there aren’t more — and maybe there will be more — theatrical attempts at communicating about this issue. I think there probably will be.

STEVE: I think there will be too. In American theater, we tend to do plays about human relationships and the things that can happen with them. Going into territory that involves non-human things, like the climate or natural systems, seems to be sort of outside the realm of what theater deals with. But hopefully we can be a part of a larger movement of people who are trying to actually shift those kinds of paradigms. To be able to perceive our place in this larger system at the basis of climate change is the starting point. We, and our human behavior, and our choices, and our human relationships, and everything that we do is actually part of the world that we live in.

CYNTHIA: Right, right.

STEVE: And what we do will affect us. And each other. And other people. And, in fact, it is a very human story.

Cynthia Hopkins premiered her piece “A Living Documentary” at the American Realness Festival in January, 2015. It’s a comedic, no-nonsense reflection on the trials and tribulations of earning a living as a professional theater artist in the 21st century. For more information, visit www.cynthiahopkins.com.

Post Views:

8,802