April 29, 1996, Jonathan Larson’s “Rent” opened on Broadway, a few months after the death of its composer. It has become the dominant AIDS narrative in musical theater, although opinions on its merits and legacy differ wildly. To its advocates, “Rent” brought queer characters to the mainstream and gave marginalized populations a cultural touchstone. Others critics point out that Larson was a straight man whose tragic death had nothing to do with AIDS and claim his representation of early-90s East Village bohemia is inauthentic at best and plagiarized at worst.

This week, we are publishing conversations with artists whose work informed or descends from “Rent” to various extents. In doing so, we delve into who has the right to tell what stories.

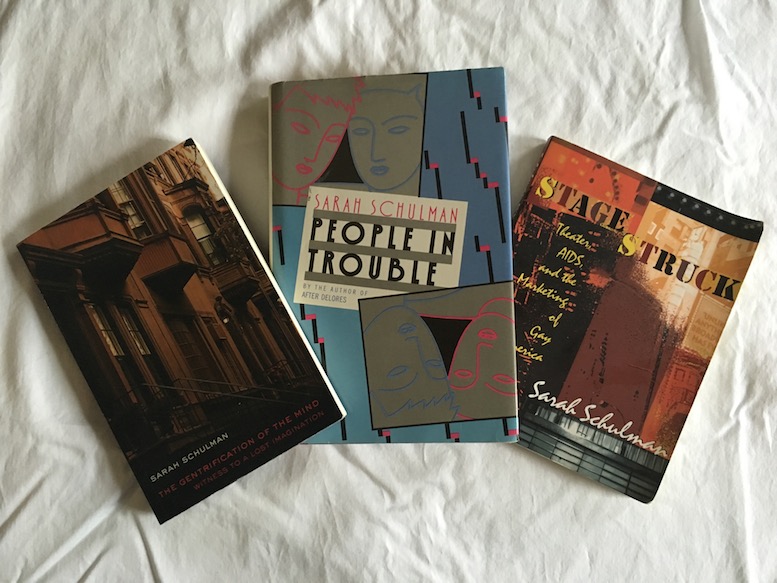

Here is the second part of a conversation that Extended Play’s Tommy O’Malley facilitated between Sarah Schulman and Chris Tyler. Schulman argues that Larson knowingly lifted characters and plot from her novel “People in Trouble,” which she documents in her 1998 book “Stage Struck.” In April 2016, Tyler produced a performance piece inspired by the legacy of “Rent” and Schulman’s work. This is the first time Schulman and Tyler ever spoke. Read the first part of this conversation here.

TOMMY O’MALLEY: In your book “Israel/Palestine and the Queer International,” you talk about Brand Israel, the public relations campaign designed by Saatchi and Saatchi that specifically targeted gay men. And you argue that the goal of Brand Israel was to “pinkwash” what I think you would call the apartheid that exists.

SARAH SCHULMAN: Right. I’m the queen of “pinkwash,” you know that. I popularized that concept, yes.

TOMMY: Yeah, so you talk about the pinkwashing that Brand Israel did in that country, how it diverted attention from a harsher reality. How has “Rent” pinkwashed the reality, for somebody like Chris or myself, of what’s happening in this city.

SARAH: That’s good. I think I laid this out in “Stagestruck,” but [in “Rent”], the gay people with AIDS die, the straight people with AIDS live, the bad landlord is black, the lesbians bicker, but the straight people really love each other. I mean it’s all that kind of stuff.

TOMMY: So how is the New York City of “Rent” different from the New York City we live in today? You talked about it in your book “Gentrification of the Mind,” but I’m curious if it’s changed even further since that book was published four years ago.

SARAH: Well, gentrification itself has transformed profoundly, because I was describing first-stage gentrification, where mixed communities are made homogenous for the first time and community-based businesses are replaced by upscale businesses. This is in the past now, because since we don’t have commercial rent control, those gentrifying businesses can no longer afford to be in those communities. So now we have late-stage gentrification where they’re being replaced by Dunkin’ Donuts and Duane Reade and all of that. But what’s coming next, I mean, I’ve seen a map of every construction that’s been approved in New York City and what it’s going to look like when they’re all built. And there’s a whole new society that’s being laid on top of our society that’s a society of luxury towers. So when you look at the future maps of Manhattan, it’s all high-rise and no public sector. None of it is being accompanied by hospitals, schools, anything. There’s a building on 57th Street that has a heliport so that people can just go to Wall Street or whatever and come back — they don’t even have to go on the street.

TOMMY: So what’s the impact on the art?

“There’s no reason for there to be MFA programs in writing. Zero reason. And it has a very, very negative impact on the culture.”

SARAH: Well, there’s, you know, for me it starts with the problem of training artists. The professionalization is where the problem begins for the artists. I mean, I’m in an art form where there’s no materials. I can see if you’re a dancer, you need to go to take class, or you know, if you are a visual artist, you need to learn how to handle materials, but there’s no reason for there to be MFA programs in writing. Zero reason. And it has a very, very negative impact on the culture… I teach low-income undergraduates and immigrants in a CUNY that has a very low graduation rate. Very few of my students go to graduate school. Like maybe, like in 16 years maybe like eight. Seriously. And when they do go to MFA programs, they don’t do well, because they get there, and they are the only poor kid, the only black kid, the only kid that doesn’t know how things work. They don’t make friends, the teachers don’t mentor them, and when they get out, even if they write a manuscript that’s good, they can’t get it published. Now, I mean part of me would love to get in on the other end. I’d like to get into an MFA program that provided funding and help those kids succeed in those programs, because I understand why they’re not succeeding. So it’s fixable. You know, because right now it’s a requirement: you have to go to those programs, there’s no way out of it. Especially if you’re poor. If your father could call somebody then you don’t have to go to those programs, but if they can’t, you have to go. So those programs — talk about branding. That’s what they’re all about. Group thinking, group training, is antithetical to art-making, which is an individuated expression. So if you’re going into a program and you have a cohort, and you all have the same teachers, and you read the same stuff, it’s disruptive to being a real artist. So that’s where a lot of the problem starts. And then you have that the city’s too expensive, and the only people who can move here are people who have money from somewhere else. The people who move here get along better with their families than the people who can’t move here, because you have to have some kind of outside function, or else do things that are illegal.

TOMMY: Or you just work 80, 90 hours a week doing five jobs.

SARAH: Yeah, but it’s hard to make art under those circumstances. It’s not impossible, but.

CHRIS TYLER: I think to everyone who participates in the making of art in the city, there’s a significant divide between the people who are funded by their families or are independently wealthy or have a kind of safety net to fall back on if things become dire, and people who do not have those kinds of resources.

SARAH: Sure, and a lot of it is where you live. All the gentrified neighborhoods are more expensive. So if you’re really just living here because you want to, like, soak it up, you really don’t have to live in those neighborhoods. But people who choose to have some kind of access to some kind of supplement.

TOMMY: So from your position, Sarah, as somebody who has been at least publishing for 32 years, probably creating art for much longer than that, to now be in a position where a younger artist is taking inspiration for your work—

SARAH: (to Chris) Thank you.

TOMMY: I’m curious what that feels like to you.

SARAH: I don’t know, because first of all, you have the right to make whatever work you want to make and say whatever you want to say, and how I feel about it is irrelevant, honestly. So that’s the most important thing. I always tell my students, I’m going say what I honestly think, but you do whatever you want. You know, so that’s the first thing. But you know, I fear becoming part of something that is antithetical to what I stand for. I have fear about that… I don’t want to be used as a branding, as a form of branding.

CHRIS: Right.

TOMMY: What happens if that’s the product?

SARAH: It doesn’t bother me that much, but it’s not my first choice. I mean, I have other things that really bother me that have nothing to do with any of this right now, ’cause of all this other shit I’m involved in. The art world is not at the forefront of my life right now.

CHRIS: Yeah. For me, I felt conscious of that potential for that very reason. And for me, the decision to include that this piece is inspired by your work was really a way of citing the sources and acknowledging from the get-go that your work was something that I had engaged with.

SARAH: Well thank you, I appreciate that.

Chris Tyler in a promotional shot for his show “R*NT (or, What You Own: another dirge for a city remembered).” Photo Credit: Eileen Meny.

CHRIS: Whenever I say that I’m working on a show about Rent, the immediate reaction of somebody in the queer performance community is, “Oh, have you read ‘People in Trouble?’ Have you read ‘Stagestruck?’” And it’s like, yes, of course! Why would I even be engaging with this if I wasn’t thinking about things larger than the property itself. And so, for me, that was just a way to be like, yes, of course this person’s writing has had a profound impact on me. But this person is also not responsible for the choices that I make.

SARAH: Right, it’s nice that you’re acknowledging it, because Jonathan Larson didn’t.

CHRIS: Right. I don’t know if “nice” is even the word.

SARAH: You know, we might end up having different interests, and that’s okay. That’s okay.

“My intention is not to make it seem like it is a Sarah Schulman-approved vehicle. These are ideas that I am grappling with.”

CHRIS: My intention is not to make it seem like it is a Sarah Schulman-approved vehicle. These are ideas that I am grappling with, and this is a way of thinking about the world that has been meaningful to me and has profoundly affected the way that I’ve moved through the city for the last six years. And it’s also trying to look at a property within dominant theater culture and unpack it and pick it apart and think about all of the other forces that went into the creation and production and dissemination of it along the way.

TOMMY: As a gay man, I can say that the way that you’ve chronicled the AIDS crisis made me feel a certain respect for the men that came before me.

SARAH: Right, who you’ll never know.

TOMMY: Who I’ll never know. And I’m curious what that has done for you, Chris. The way that Sarah has written about gay men, who could’ve been you, who could’ve been me — has it made you think about your responsibility to your art, because you have a finite amount of time to make it?

CHRIS: I mean, between the writing and then “United in Anger,” which I saw in 2012, it’s made me conscious of their existence. I didn’t know any of this, growing up. And it wasn’t until I got here and I started looking beyond what had been served up in the past, that I came to realize that there is an entire generation of people and thinkers and oppositional creative types who are just not here and that I had never had access to. And I don’t think that’s a particularly revolutionary experience, but on a personal level, it was powerful, and it was really important to me. And when I started to realize that there was actually a community of people and a lineage and a history of feeling oppositional to power structures in the world, it had a huge impact on my life and on my practice. And so for that I’m tremendously grateful.

TOMMY: Did it make you think about the sexual culture among gay men of the millennial generation? How are you responding to being a gay man of your generation because of this work?

CHRIS: I think it’s complicated. So you have the kind of mainstream gays, largely white, largely moneyed or aspirational population, who often live on the island of Manhattan in Hell’s Kitchen and Chelsea and Greenwich Village. And then you have this other Brooklyn gay that somehow asserts itself, its brand, as antithetical to that Manhattan culture.

SARAH: Like East Village used to be to West Village.

CHRIS: Right. And I feel complicated by all of it, because I do think that it is all branding. And it’s branding that extends into interpersonal relations, and that is a scary thing to me. It’s something that I know I also participate in. And I think that when everybody is rushing to articulate their identity, whether or not that identity is in opposition to something else, it reduces the potential to engage honestly and thoughtfully with the rest of humanity. And I guess I just wish that people talked to each other more and listened to each other more.

TOMMY: Are you talking about gay men?

CHRIS: Yeah, I mean I’m talking about both. For me obviously the most immediate population is gay men. I don’t want us to settle into this space of political innocuousness because we are able to marry each other now. Because I think what’s really fascinating about the history of gay men is that you have moments like the 1980s, early-90s, when they formed coalitions with other oppressed communities in order to fight something within the dominant culture. And I think that there’s power in that kind of coalition. I think there’s a lot of potential for change in the world, I think that white gay men have access to a lot of power systems that a lot of other people don’t. And I just want us to do better.

TOMMY: For me, “Rent” was tremendously profound, growing up Irish Catholic and never seeing queer people, so that was my first real access to them. I look at it differently now, of course, as a 33-year-old man, but I still feel sort of a debt of gratitude to that show. And one of the things that made “Stagestruck” so profound, Sarah, is that you write about Jonathan Larson with a certain amount of righteous anger, which you’re totally entitled to. But you also write about him with tremendous empathy, particularly in the way that you discuss his death, and him dying because he was a poor artist. My question for you is, do you see any benefit to “Rent” existing in the world?

SARAH: (Laughing.) No.

TOMMY: Why.

SARAH: I don’t believe in trickle-down. And that was Reagan’s claim, right? That if something untrue happens at the highest level, somehow truth is going reach the lowest levels. I’ve never seen that work that way.

TOMMY: There’s no benefit to that show.

SARAH: No. Have you seen Celluloid Closet? It’s Vito Russo’s history of gay representation in the cinema. He made it with Lily Tomlin. And he shows you how — he was older than me — but he would go to the movies and watch gay people being depicted as the most evil scum, ugly, horrible, disgusting monsters, and yet it told him that he wasn’t alone. And so he was able to derive something positive from that relationship. On those grounds, maybe you could justify “Rent,” because it told you that you weren’t alone.

TOMMY: So knowing that Chris is embarking on this journey with his piece, is there anything that you want him to know?

SARAH: I want you to read the Wilhelm Reich book “People in Trouble,” which I named my novel after. I mean, it’s not an easy read. He goes to see a demonstration, and he sees soldiers, and they’re coming and they’re shooting at the workers, and he realizes that they’re the same.

TOMMY: Chris, are you going invite Sarah to come see the show?

SARAH: (Laughing.) You going to give me a free ticket?

CHRIS: Yeah, I think we can arrange a free ticket.

SARAH: So, yeah.

CHRIS: I don’t know, the act of discourse is a peculiar one, because you put things out into the world and then they’re interpreted in a myriad of ways.

SARAH: Yeah. I mean, I named my book after Wilhelm Reich, he has no say. And I don’t know if any Reichian would agree with what I’ve done with it.

CHRIS: Right.

SARAH: So it’s just part of the whole artistic process.

Post Views:

1,039