If you have not yet had the opportunity to see a piece by Ping Chong & Company, it’s high time you acquaint yourself with the stunning work of this New York theater innovator. “Beyond Sacred” opened on April 29, 2015, at the LaGuardia Performing Arts Center, and provided yet another thought-provoking exploration of a specific community’s human experience. This piece examines Muslim identity from the point of view of young people who came of age in a post-9/11 New York City, at a time of increasing Islamophobia. Participants represent a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds: those who have converted to Islam, those who were raised Muslim but have since left the faith, those who identify as “secular” or “culturally” Muslim, and those who are observant on a daily basis. With this collection of diverse voices, “Beyond Sacred” asked its audience to engage dynamically with a contentious contemporary discussion — a practice Chong has consistently staged throughout his varied career.

I had the chance to talk to Chong, the inveterate documentary theater maker, about his career and current projects. When I walked into his office for our interview, I found Chong sitting backwards in a swivel chair, looking at pictures of Russian chain mail online. He wasn’t shopping; he was doing research for a work-in-progress on Alaska. Now in his late-60s, Chong continues to explore humanity with the same enthusiasm that established him forty-something years ago.

“I’m interested in looking at the phenomenon of the human race in all its peculiarity,” Chong told me. “I like looking at us, homo sapiens, as if we’re animals in a zoo.”

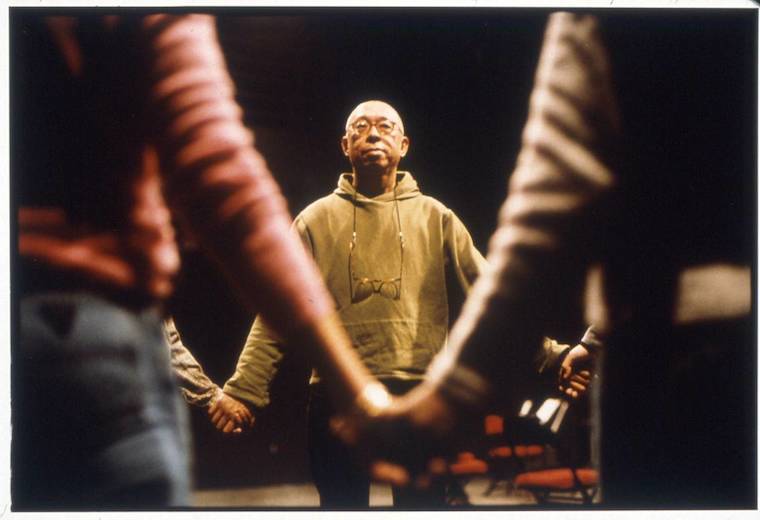

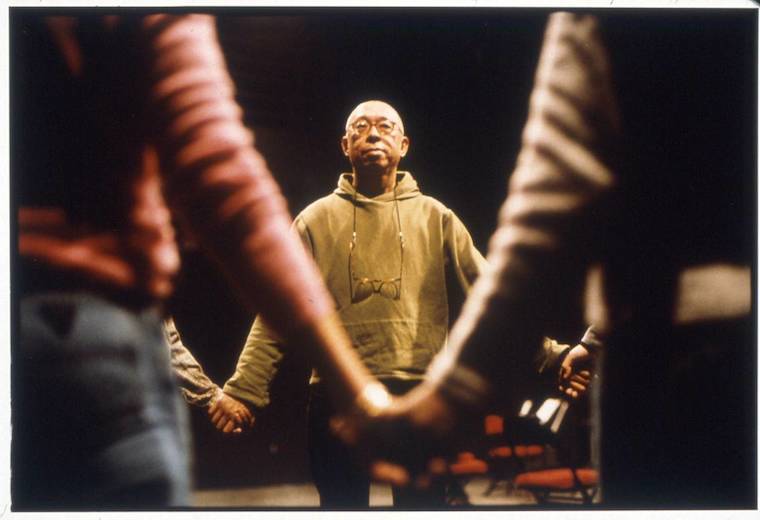

Ping Chong and “Children of War” cast members. Photo Credit: Chris Hartlove

At the beginning of his career, Chong trained with interdisciplinary theater pioneer Meredith Monk. That foundation — along with other early inspirations, such as film, visual arts, Chinese opera, and dance — continues to inform his signature documentary style. In his work, he has employed dynamic movement, projection, puppetry, and various other media, even as it emphasizes the primal dramatic experience of listening to people talk. In the 1970s and 1980s, Chong’s work was primarily allegorical, fable-like and poetic. But in 1990, his East-West Quartet signaled a shift to more historically-focused work; Chong wrote in the staging notes for “Deshima,” the first piece in the series, “I describe ‘Deshima’ as a poetic documentary. A ‘documentary’ because each element in the production — the text, choreography, gesture, sound and visual design — is inspired by an incident in the complicated history between Japan and the West. ‘Poetic’ because the form is associative not narrative. ‘Deshima’ raises questions but does not answer them.” Sometimes overtly political, other times more gentle in its biographical focus, Chong’s oeuvre is markedly non-psychological, exploring human “certainties” that turn out to be false, or delusional, when the factual material is examined through an anthropological lens.

Although much of Chong’s work since 1990 has been based in historical inquiry, his purest work in documentary theater began with his “Undesirable Elements” series in 1992. Based on interviews with members of a specific community, Chong choreographs a staged presentation in which the subjects share their stories in a scripted fashion. These performances are highly stylized; synchronicity and repetition are common, and sentences often weave through the mouths of several actors, each picking up where another left off. In this way, individual performers not only tell their own stories, but also help to narrate those of fellow cast members. Performers sit in a semi-circle of chairs on stage, reading from their scripts on music stands, and punctuating the dramatic beats of the piece with simultaneous claps. The simplicity of this staging is crucial to the success of “Undesirable Elements” performances: not only do the stories speak for themselves, but the untrained performers tell their own stories.

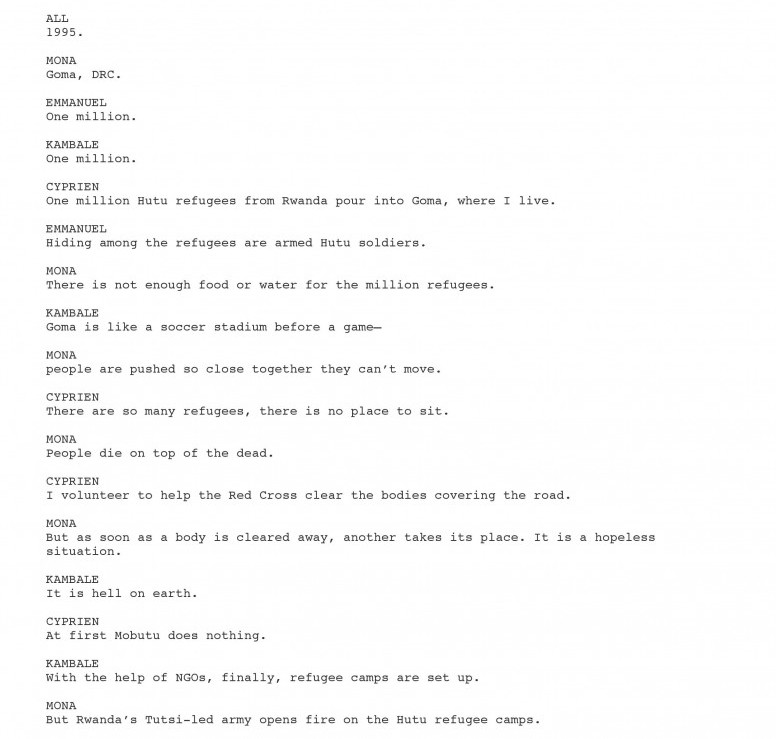

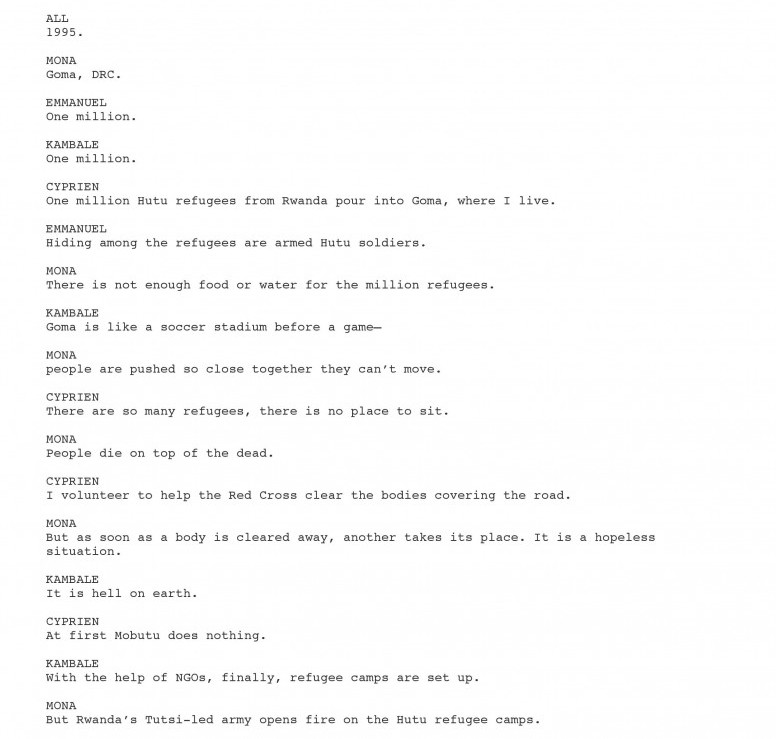

“Cry for Peace” cast members. Photo Credit: Jamie Young

For example, to create “Cry for Peace: Voices from the Congo,” Chong interviewed members of the Congolese refugee community in Syracuse, NY. He and dramaturg Kyle Bass then selected five representative members to perform the piece, including a local Congolese community leader, a former child soldier, and a biracial woman whose Belgian father was a link to Congo’s Western colonizers. Following is an excerpt from “Cry for Peace: Voices from the Congo,” which premiered at Syracuse Stage in September 2012:

Chong has described the creation of “Undesirable Elements” as staging “a seated opera for the spoken word,” focusing the audience’s attention on people whose stories are all too frequently unheard or undervalued in the formal historical narrative. As much as possible, he includes other languages in his scripts, often untranslated, highlighting the experience of “otherness” in the community depicted. Productions do not require a typical theater setting and have consequently taken place in auditoriums, community centers, the Hall of Crustaceans at the American Museum of Natural History, and a beauty salon in Saint Paul, Minnesota. There have been over 40 productions in the series, exploring issues such as childhood sexual abuse, life with physical disabilities, immigration, childhood survivors of war, and gentrification in Brooklyn.

Chong has described the creation of “Undesirable Elements” as staging “a seated opera for the spoken word,” focusing the audience’s attention on people whose stories are all too frequently unheard or undervalued in the formal historical narrative. As much as possible, he includes other languages in his scripts, often untranslated, highlighting the experience of “otherness” in the community depicted. Productions do not require a typical theater setting and have consequently taken place in auditoriums, community centers, the Hall of Crustaceans at the American Museum of Natural History, and a beauty salon in Saint Paul, Minnesota. There have been over 40 productions in the series, exploring issues such as childhood sexual abuse, life with physical disabilities, immigration, childhood survivors of war, and gentrification in Brooklyn.

Chong concludes every “Undesirable Elements” piece with the story of each performer’s naming and birth, reminding the audience of the singular experience of each individual within the broader scope of the historical context the piece has explored. Again, an excerpt from “Cry for Peace: Voices from the Congo” follows:

Since the “Undesirable Elements” series came into existence, it has been cross-breeding with Chong’s collage documentary form. In his most recent interdisciplinary work, “Collidescope,” Chong drew imagery from the Trayvon Martin crime scene in Sanford, Florida, and the Michael Brown memorial in Ferguson, Missouri. For the text, he excerpted transcripts from Clarence Darrow’s final defense at the murder trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet in Detroit, Paul Robeson’s interrogation before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Lyndon B. Johnson’s phone conversations during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and an abridged slave petition for freedom rights before the American Revolutionary War. As he re-examines and re-imagines the human race through his work, Chong always works with multimedia elements, incorporating audio, video and primary source visuals, such as photographs. Sometimes he quotes verbatim from his primary source materials; other times, he takes poetic license, in order to pack a bigger punch.

Since the “Undesirable Elements” series came into existence, it has been cross-breeding with Chong’s collage documentary form. In his most recent interdisciplinary work, “Collidescope,” Chong drew imagery from the Trayvon Martin crime scene in Sanford, Florida, and the Michael Brown memorial in Ferguson, Missouri. For the text, he excerpted transcripts from Clarence Darrow’s final defense at the murder trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet in Detroit, Paul Robeson’s interrogation before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Lyndon B. Johnson’s phone conversations during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and an abridged slave petition for freedom rights before the American Revolutionary War. As he re-examines and re-imagines the human race through his work, Chong always works with multimedia elements, incorporating audio, video and primary source visuals, such as photographs. Sometimes he quotes verbatim from his primary source materials; other times, he takes poetic license, in order to pack a bigger punch.

In order to indoctrinate other theater-makers into his creative methodology, the company hosts an annual Training Institute, as well as periodic workshops for those interested in learning more about his technique. In addition, the “Secret Histories” Arts-in-Education program brings the “Undesirable Elements” series to schools around the world, by staging a professional “Undesirable Elements” performance, followed by an in-school artistic residency. During the residency, teaching artists work with students to develop a personal narrative and present it in a cumulative theatrical performance. Having observed one such residency in Flushing, Queens, I can attest to the remarkable efficacy of teaching this form of storytelling to students, who are empowered by the structure of the “Undesirable Elements” style and emboldened by the respect granted to their personal stories. Jessica Hagedorn, who participated in one of Chong’s workshops at Basement Workshop in the 1980s, wrote, “I took a lot away from that workshop, but the most valuable thing he taught us, which stays with me even today, was how to conjure theatre from seemingly random elements — a litany of foreign and English words, a chronology of events, a song, an object from someone’s home. Simply put, in that class we learned the art of juxtaposition, of which Ping is a master.”

“Cocktail” cast members. Photo Credit: Louisiana State University

The beauty of Chong’s historical theater is the way that it values an exploratory research process, truly tailoring the concept of “investigative” or “documentary” theater to his own aesthetic of juxtaposition and unanswerable questions. Although his commissions are often very specific, his imagination and energy appear boundless in the way that he applies himself to cultivating the interwoven historical, visual, fictional, and dramatic elements of each production.

Chong has been a vital player in the recent wave of documentary, or investigative, theater that is explosively popular in America, so it is no surprise that his knack for depicting specific realities has been so successful. Twentieth-century America has seen three major movements of documentary theater: one in the 1930s, one in the 1960s, and most recently, since the 1980s, with pioneers such as Anna Deavere Smith and Emily Mann. Today we see reverberations of the work that Smith, Mann and Chong did in the 1990s in the immense popularity of Sarah Koenig’s “Serial” podcast and the HBO true-crime series “The Jinx.” Considering the recent surge in popularly of such work, he hypothesizes that this generation is particularly captivated by stories with an element of truth or reality in them. “Reality is incredibly peculiar and strange,” he said. “I don’t even need fiction. After all human culture is a form of creation, of artifice.”

Post Views:

2,070

Chong has described the creation of “Undesirable Elements” as staging “a seated opera for the spoken word,” focusing the audience’s attention on people whose stories are all too frequently unheard or undervalued in the formal historical narrative. As much as possible, he includes other languages in his scripts, often untranslated, highlighting the experience of “otherness” in the community depicted. Productions do not require a typical theater setting and have consequently taken place in auditoriums, community centers, the Hall of Crustaceans at the American Museum of Natural History, and a beauty salon in Saint Paul, Minnesota. There have been over 40 productions in the series, exploring issues such as childhood sexual abuse, life with physical disabilities, immigration, childhood survivors of war, and gentrification in Brooklyn.

Chong has described the creation of “Undesirable Elements” as staging “a seated opera for the spoken word,” focusing the audience’s attention on people whose stories are all too frequently unheard or undervalued in the formal historical narrative. As much as possible, he includes other languages in his scripts, often untranslated, highlighting the experience of “otherness” in the community depicted. Productions do not require a typical theater setting and have consequently taken place in auditoriums, community centers, the Hall of Crustaceans at the American Museum of Natural History, and a beauty salon in Saint Paul, Minnesota. There have been over 40 productions in the series, exploring issues such as childhood sexual abuse, life with physical disabilities, immigration, childhood survivors of war, and gentrification in Brooklyn. Since the “Undesirable Elements” series came into existence, it has been cross-breeding with Chong’s collage documentary form. In his most recent interdisciplinary work, “Collidescope,” Chong drew imagery from the Trayvon Martin crime scene in Sanford, Florida, and the Michael Brown memorial in Ferguson, Missouri. For the text, he excerpted transcripts from Clarence Darrow’s final defense at the murder trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet in Detroit, Paul Robeson’s interrogation before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Lyndon B. Johnson’s phone conversations during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and an abridged slave petition for freedom rights before the American Revolutionary War. As he re-examines and re-imagines the human race through his work, Chong always works with multimedia elements, incorporating audio, video and primary source visuals, such as photographs. Sometimes he quotes verbatim from his primary source materials; other times, he takes poetic license, in order to pack a bigger punch.

Since the “Undesirable Elements” series came into existence, it has been cross-breeding with Chong’s collage documentary form. In his most recent interdisciplinary work, “Collidescope,” Chong drew imagery from the Trayvon Martin crime scene in Sanford, Florida, and the Michael Brown memorial in Ferguson, Missouri. For the text, he excerpted transcripts from Clarence Darrow’s final defense at the murder trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet in Detroit, Paul Robeson’s interrogation before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Lyndon B. Johnson’s phone conversations during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and an abridged slave petition for freedom rights before the American Revolutionary War. As he re-examines and re-imagines the human race through his work, Chong always works with multimedia elements, incorporating audio, video and primary source visuals, such as photographs. Sometimes he quotes verbatim from his primary source materials; other times, he takes poetic license, in order to pack a bigger punch.